The world of the hell-dwellers is the lowest of the Ten Worlds. Buddhist cosmology teaches that there are more than 100 hells, including the eight major hot hells and eight major cold hells, which are reserved for those who are so consumed with hatred, bitterness, and despair that their only wish is to destroy themselves and others out of spite and the desire for non-existence.

Lotus SeedsQuotes

Hossō School’s Two Categories of Buddha Nature

The Hossō School’s position was that two categories of Buddha nature could be identified: the ribusshō, which all men possessed, and the gyōbusshō, which only a few possessed. The first was the Buddha-nature as absolute. Since the absolute was the basis of all phenomena, and since all sentient beings were ultimately dependent on the absolute, all were said to possess the ribusshō. However, Hossō scholars argued that the absolute was static; it did not actively participate in the phenomenal realm. Consequently, the ribusshō did not enable a practitioner to attain Buddhahood. When a sūtra stated that all sentient beings possessed the Buddha-nature, it indicated only that all had the ribusshō, not that all could attain Buddhahood.

The potential of some sentient beings to attain Buddhahood was explained by postulating a second type of Buddha-nature, the gyōbusshō or Buddha-nature of practice. The gyōbusshō consisted of untainted seeds (muro shuji) which were stored in the eight or basic consciousness (arayashiki, Skt. ālaya-vijn͂ana). These seeds were said to have existed from the beginningless past. If a person possessed them, he could attain Buddhahood. However, if he lacked untainted seeds, he could not create them no matter how diligently he practiced or studied. A person without the gyōbusshō could therefore never attain Buddhahood. Hossō School monks interpreted statements in the sūtras that only certain people could attain Buddhahood as referring to the possession of gyōbusshō by those people. Since not everyone had the gyōbusshō, some sūtras contained statements that not everyone could attain Buddhahood.

Saichō: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School, p97-98Saichō’s Teacher Hsing-man

The small amount of reliable information that survives about Saichō’s teacher Hsing-man is found in Saichō’s Kechimyakufu. Hsing-man, a native of Su-chou (in modern Kiangsu), was initiated when he was twenty and ordained as a monk when he was twenty-five. He studied the Ssu fen lü precepts for five years. In 768 he met Chan-jan and attended a number of his lectures on Chih-i’s major works (Tendai sandaibu). At the time of Saichō’s arrival in China, he was the head of the Fo-lung temple on Mount T’ien-t’ai. Hsing-man encouraged Saichō in his studies, giving him eighty-two fascicles of T’ien-t’ai works. He also told Saichō that Chih-i had predicted that a foreign monk would come to China in order to propagate T’ien-t’ai teachings in a country to the east of China. Predictions such as this one probably helped foreign monks such as Saichō and Kūkai gain ready acceptance by Chinese monks. Hsing-man assiduously practiced religious austerities and authored a number of works. He died around the year 823 when he was over eighty years old.

Saichō: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School, p46Saicho’s Intention to Establish the Tendai School in Japan

In his petition asking that students be sent to China, Saichō claimed that the Tendai texts transmitted to Japan contained many copyist errors. In addition, a direct transmission from Chinese teachers to Japanese students was needed to insure the orthodoxy of the Tendai School in Japan. Saichō criticized both the Hossō and Sanron schools for being based on Sāstra (commentaries), not on sūtras (the Buddha’s words). Hossō and Sanron monks considered only the branches of the Buddha’s doctrines and neglected the roots. Tendai teachings, because they valued the Lotus Sūtra above all other authorities, were not subject to this criticism. Thus even before he went to China, Saichō declared his intention to establish the Tendai School in Japan.

Saichō: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School, p38A Method of Gradual Guidance

Those who could not learn [the] simple lesson in karma could not hope to comprehend the law of dependent origination or the Four Noble Truths. Comprehension of the triple doctrine enabled aspirants to cleanse their minds of false doctrines and preconceptions. Once the dross had been purged away, they were ready to move on to more advanced teachings. In other words, the Buddha employed a method of gradual guidance leading from the easy to the hard. Several primitive sutras contain passages like the following, explaining this gradual approach:

“To one seated before him, the World-honored One preached the Law gradually. First he taught giving, obeying the precepts, and [thereby] rising to heaven. Then he explained that selfish desires are evil and the cause of both misfortune and impurity, whereas separating oneself from selfish desires is a great virtue. This teaching made the heart of the listener malleable and receptive; the person put aside prejudices and experienced the ecstasy of faith. When this happened, the World-honored One for the first time preached the Four Truths of suffering, desire, nirvana, and the Way. As freshly washed and bleached fabric receives the dye, the listener received the Four Truths. While still seated there, the listener acquired the pure and unsullied Eye of the Law [which sees that all things arising from causes are ultimately extinguished].”

Basic Buddhist Concepts

Devoting Oneself to Buddha’s Teaching

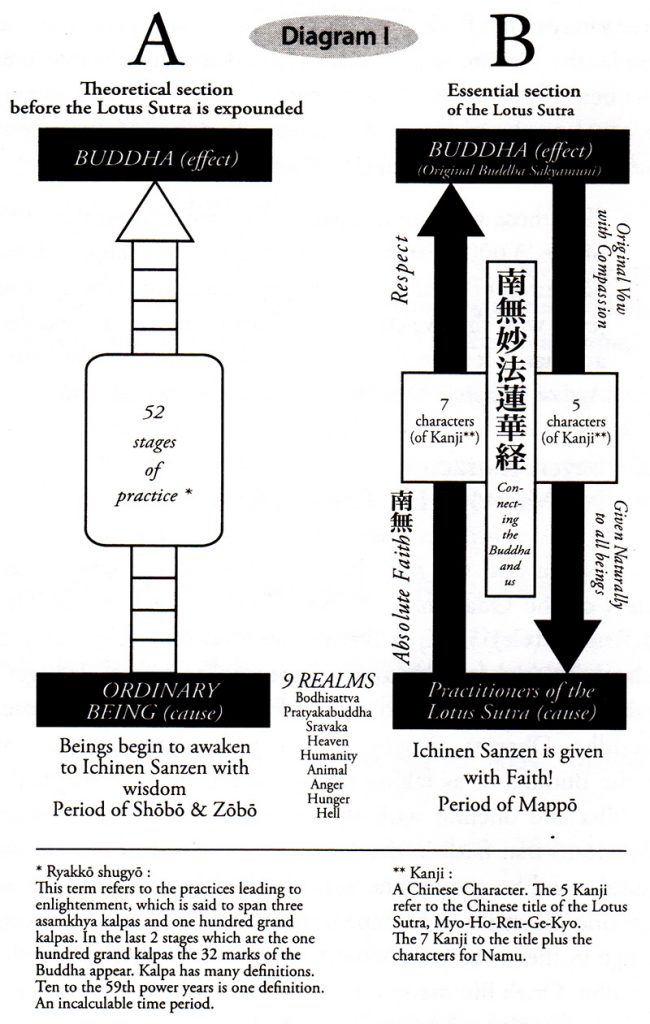

As Column B indicates, we merge with the Odaimoku. It is “Namu” or devotion. Then the Odaimoku merges with us. It is Jinen Jōyo, or transferring naturally. It is not awakening to Ichinen Sanzen with one’s own wisdom, but the Buddha’s Ichinen Sanzen is transferred naturally by one’s faith of Namu, devoting oneself to the Buddha’s teaching.

Nichiren Shōnin stated in Kanjin Honzon Shō,

… Śākyamuni Buddha’s merit of practicing the bodhisattva way leading to Buddhahood, as well as that of preaching and saving all living beings since His attainment of Buddhahood are altogether contained in the five words of Myo, Ho, Ren, Ge and Kyo and that consequently, when we uphold the five words, the merits which He accumulated before and after His attainment of Buddhahood are naturally transferred to us.”

(WNS2, p. 146)

He also stated in Kanjin Honzon Shō,

“For those who are incapable of understanding the truth of the ‘3,000 existences contained in one thought,’ Lord Śākyamuni Buddha, with his great compassion, wraps this jewel with the five characters of Myo, Ho, Ren, Ge, and Kyo and hangs it around the neck of the ignorant in the Latter Age of Degeneration.”

(WNS2, p. 164)

The Most Popular Single Sūtra During the Nara Period

The Lotus Sūtra (Tno. 262) in its translation by Kumārajīva done in 406 was the most popular single sūtra during the Nara period. It was required that all yearly ordinands be able to read it. It is the most commonly mentioned sūtra in documents recommending laymen for ordination as monks. … The Lotus Sūtra was also frequently recited at the request of the court in order to protect the state. It does not have any specific passage which guarantees protection of the state, as did most of the other sūtras used for this purpose. Rather, this use of the sūtra stems from its claim that it is the most authoritative of all sūtras and from stories that those with faith in the sūtra were protected from harm. In addition, it was a very popular sūtra among the common people, being the sūtra most often mentioned in the Nihon ryōiki.

Saichō: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School, p24-25, Note 32State Buddhism and the Ordination of Monks

One of the distinguishing characteristics of Buddhism during the Nara period (710-784) was the lavish expenditure of money by the state for temples, Buddhist images, and the copying of Buddhist texts. The merit from such activities was often devoted to the protection of the state and its ruler from various catastrophes. Records of Buddhist activities during the Nara period reveal that the ceremonies performed and the sūtras chanted were often directly related to state Buddhism. The establishment of a nationwide system of provincial temples (kokubunji) with the Tōdaiji temple at Nara as its center is one of the crowning achievements of state Buddhism at this time. Buddhism was thus used to integrate the provinces and the capital.

Qualified monks were required to keep the system functioning. The monks had to be able to chant the sūtras which would protect the state. They also were expected to have led a chaste life so that they could accumulate the powers for the ceremonies to be effective. In order to ensure that the men who joined the Buddhist order were able to perform these ceremonies, the court established requirements which candidates for initiation as novices or ordination as monks had to meet. According to an edict issued in 734, a candidate for initiation was required to be able to chant the Lotus Sūtra (Fa hua Ching, Skt. Saddharmapuṇḍrikasūtra) or the Sūtra of Golden Light (Chin kuang ming Ching, Skt. Suvarṇaprabhāsasūtra), to know how to perform ceremonies worshiping the Buddha, and to have led a chaste life for at least three years. The requirements were designed to ensure that the candidate would be able to effectively perform religious ceremonies. Little attention was paid to the candidate’s ability to explain Buddhist doctrine. If a candidate met the requirements, he would be initiated at the court at the beginning of the year, with the merit resulting from his initiation devoted to the welfare of the state. Successful candidates were called “yearly ordinands.”

Saichō: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School, p4-5The Delightfulness of Buddhism

When we are able to approach the Dharma with joy and delight we are able to go much further in our practice. When we have joy in our practice we are less likely to be distracted or become sidetracked. All of that enables us to have even greater joy. But when we cling too tightly to effort and form and correctness we in effect strangle out the delightfulness of Buddhism. Practice the Dharma as if it were and ice cream cone. Enjoy it or it will melt in your hand.

Lotus Path: Practicing the Lotus Sutra Volume 1Shock and Awe Buddhism

I think the authors of the Lotus Sutra wanted to shock the shit out of their readers, to slap them in the face or pour buckets of cold water on them, a sort of a shock and awe of Buddhism. First, the ultimate truth of Buddhism is that we are all capable of becoming Buddhas. Second, there isn’t a whole bunch of petty differing ways of going about attaining Buddhahood. Third, we should quit expecting others to do for us what we are fully capable of doing for ourselves.

Lecture on the Lotus Sutra