In the first chapter heavenly flowers fall on both the Buddha and his listeners, indicating the equality of both. That idea is extended in chapter 3 with the idea that the Buddha preaches only to bodhisattvas. The point is that to preach the Dharma is to be a bodhisattva — and to hear the Dharma is to be, to that degree, a bodhisattva. This is because really hearing is to take it into one’s life, thus to practice it, thus to be a bodhisattva. Thus, it can be said that the buddhas come into the world only to transform people into bodhisattvas.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 192

Quotes

Appropriate Devices

Sometimes the Buddha has to use appropriate devices in order to lead others to realize their potential. But this does not mean that any trick will do. The Buddha’s devices are always appropriate – i.e., designed for the benefit of the recipient. The father thought about what would be appropriate for these particular children in this particular situation.

Even the very fancy cart which the father gives to the children is, after all, only a cart, a vehicle. All teachings and practices should be understood as devices, as possible ways of helping people. They should never be taken as final truths. But the fact that they can be and are used to save people means that they are very important truths, that is, sufficient to save people.

Thus in the Lotus Sutra, teaching is not teaching, or at least it is not

Dharma teaching, unless someone is taught.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 192

The Ten Worlds: Bodhisattvas

Of the Four Higher Worlds – voicehearers, privately awakened ones, bodhisattvas, and buddhas – the world of bodhisattvas is the world viewed as the world of compassionate endeavor, specifically the cultivation of the Six Perfections. Those who view the world in this way are not seeking to flee the world of birth and death, but stay within it in order to assist and teach others.

Lotus SeedsThe Burning Playgrounds

[The Parable of the Burning House] is interpreted as saying that the world is like a burning house. But the idea of escaping from the world is not what the sutra teaches. Elsewhere it makes clear that we are to work in the world to save others. The point here, I think, is more that we are like children at play, not paying enough attention to the environment around us. Perhaps it is not the whole world that is in flames, but our playgrounds, the private worlds we create out of our attachments and out of our complacency. Thus, leaving the house is not escaping from the world but leaving behind our play-world, our attachments and illusions, or some of them, in order to enter a real world.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 191

The Religious Spirit

Concern for religion may start with various motives. It may be less a dissatisfaction with reality than a desire for status or profit. It may begin as indefinite theoretical or philosophical curiosity or as mere habit. Furthermore, the fear of reality that leads some people to religion varies in degree and intensity and therefore may be expected to result in equally varied degrees of faith. But it is the religious spirit, no matter what its source, that is the fundamental force inspiring people to seek the ideal state.

Basic Buddhist Concepts

The Many Paths Within the Great Path

Parables are analogies, but never perfect ones. [The Parable of the Burning House] provides an image of four separate vehicles. But if we follow the teaching of the sutra as a whole, the One Buddha Way is not an alternative to other ways; it includes them. A limitation of this parable is that it suggests that the diverse ways (the lesser carts) can be replaced by the One Way (the special cart). But the overall teaching of the sutra makes it plain that there are many paths within the Great Path, which integrates them, i.e., they are together because they are within the One Way. To understand the lesser ways as somehow being replaced by the One Way would entail rejecting the whole idea of the bodhisattva-way, which the sutra clearly does not do. In fact, the whole latter part of the sutra is a kind of extolling of the bodhisattva-way. Also, in the story itself, in running out of the burning house the children are pursuing the śrāvaka, pratyekabuddha, and bodhisattva ways. In terms of their ability to save, the three ways are essentially equal. They all work.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 191

Learning from Difficulties

Here [in the story about Wonderful Voice Bodhisattva’s visit] again is expressed the idea that the sahā world, despite its obvious shortcomings, is something special, and that this is related to the presence in it of Śākyamuni Buddha. There may be other reasons for this, but I suppose that the great size and magnificence and accomplishments of the Bodhisattva Wonderful Voice contribute to the enhancement of the sahā world and Śākyamuni, since he comes to the sahā world to pay tribute to Śākyamuni Buddha.

In fact, there seems to be an implication here, and in other instances where bodhisattvas come from outside the sahā world to visit Śākyamuni Buddha, that the sahā world is especially important because it is a more appropriate, that is, more difficult, place for bodhisattva practice. One of the repeated themes of the sutra is that one can and should learn from difficulties. Salvation, in this world, is not a matter of freedom from suffering and distress, but rather an ongoing process of overcoming evil by helping others. In this sutra, for example, Śākyamuni Buddha simply thanks Devadatta, well known elsewhere as the personification of evil, for being his teacher, and predicts that Devadatta too will become a buddha. In this sense, this world offers many opportunities for one to enter the Buddha-way through bodhisattva practice.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 188-189

The Significance and Magnificence of Śākyamuni Buddha

In chapter 16, the Buddha has made clear that he is alive at all times and, in this sense, universal or eternal. In chapter 17, having heard this, an incredibly large number of living beings, bodhisattvas, and bodhisattva mahāsattvas receive various blessings, such as the ability to memorize everything heard, unlimited eloquence, power to turn the wheel of the Dharma, supreme enlightenment after eight, four, three, two or one rebirths, or the determination to achieve supreme enlightenment. In all twelve different groups within the congregation assembled to hear the Buddha preach are mentioned here, each of them enormously large, and each having received various blessings as a consequence of hearing about the everlasting life of the Buddha.

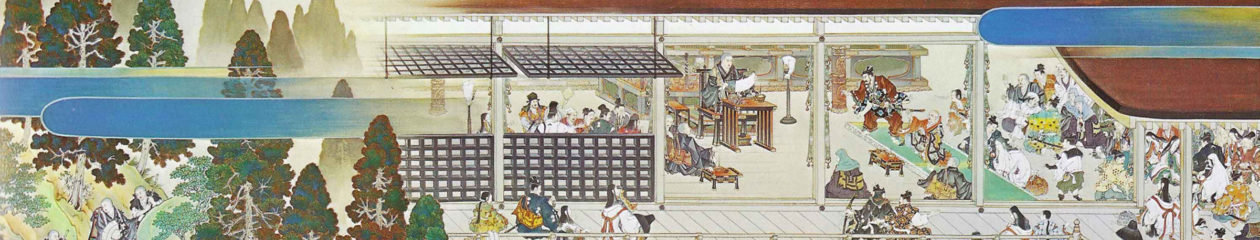

In response to this joyous occasion, the gods in heaven(s) rained beautiful flowers and incense down on the innumerable buddhas of the ten directions who had assembled in the sahā world, on Śākyamuni Buddha and Many Treasures Buddha, then sitting together in the latter’s magnificent stupa, and on the great bodhisattvas, and on the monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen assembled there. Deep in the sky, wonderful sounding drums reverberated by themselves. The many Indras and Brahmas from the other Buddha-lands came. Then the gods rained all kinds of heavenly jewel-encrusted garments in all directions, and burned incense in burners which moved around the whole congregation by themselves. And above each of the buddhas assembled under the great jeweled trees, bodhisattvas bearing jeweled streamers and such, and singing with wonderful voices, lined up vertically, one on top of the other, all the way to the heaven of Brahma.

Clearly the events depicted here are both magical and cosmological in scope. The story involves countless worlds, buddhas, bodhisattvas, and wondrous events with flowers, sound, and incense — all in praise of the revelation, in the sahā world, of the good news of the Buddha’s ever-presence. Within the story it is, in a sense, important that there are many worlds in ten directions, and gods as well as buddhas, bodhisattvas, and humans. But, in another sense, how many directions there are, or how many different kinds of beings there are, has virtually no importance. In fact, here and I think only here, the text refers to nine directions, rather than the usual ten. What is important is that no matter how many directions there are, no matter how many worlds there are, and no matter how many kinds of living beings there are, all are delighted and transformed by and extol the ever-presence of the Buddha — the fact that none of them ever is or ever was or ever will be without the presence of the Buddha. The story uses a cosmological setting, but it does so for the purpose of proclaiming the significance and magnificence of Śākyamuni Buddha, the Buddha of the sahā world.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 186-187

Radically Affirming the Reality and Importance of This World

Here there is an apparent contradiction — the sutra clearly insists that there is no time in which the Buddha is not present, but it also claims that he became a buddha. Chapter 16 answers Maitreya’s question at the end of chapter 15 by teaching that Śākyamuni has been a buddha from the very remote past, but this does not explain how he both always is and yet became enlightened. What is involved here, I think, is that on the one hand, in order both to affirm this world and to identify the Buddha with the Dharma, the everlasting process which is the truth about the nature of things, it is important to have him be eternal or everlasting. Just as there is, and can be, no place from which the Buddha is completely absent, there is no time in which the Buddha is not present. On the other hand, the very meaning of “enlightenment” requires that it be a process, and thus requires that Śākyamuni Buddha became enlightened. In fact, in several places the Lotus Sutra teaches that Śākyamuni Buddha became enlightened only after countless kalpas of bodhisattva practice. Further, only if he became enlightened could Śākyamuni Buddha be a model for others or an encouragement for them to enter the Buddha-way. So an apparent contradiction remains unresolved.

The sutra can be indifferent to such problems because they are soteriologically unimportant. Just as in chapter 24 when the Bodhisattva Wonderful Voice expresses to the Buddha of his own land his desire to visit the sahā world to pay tribute to Śākyamuni Buddha, and that Buddha warns him that even though the sahā world is not smooth or clean and its buddha and bodhisattvas are short, he should not disparage or make little of that world or think that its buddha and bodhisattvas are inferior. In this story too the point is that the sahā world is not to be regarded as inferior. In other words, the real point here is an affirmation of the sahā world. It is, we are told, a world which should not look for help from other worlds because it does not need help from elsewhere.

Thus the use of miracle stories in the Lotus Sutra is exactly the opposite of what is so often the case. Instead of using stories of other worlds as a way of encouraging escape from or negligence toward this world, in the Lotus Sutra stories of other worlds are used to radically affirm the reality and importance of this world.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 185-186

The Empty Space Beneath the Sahā World

Exactly what is meant by the empty space in the lower part of the sahā world below the earth is unclear. Probably it is simply the most convenient way to have this huge number of bodhisattvas be hidden, yet not be in the less than human regions within the earth, and not be among the heavenly deities, yet still be in the sahā world. In other words, both for the sake of the story and for the sake of the central message of the Lotus Sutra, it is important that these bodhisattvas be both hidden and of this world.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 184