[Among those individuals, for whom imperialist aspirations, inflated to the proportion of millennial visions, inspired and legitimated violence], an important example is the revolutionary Kita Ikki (1883-1937), who advocated national socialism and strong imperial rule. …

Japan’s destiny, in Kita’s view, was to lead the rest of Asia in throwing off the yoke of Western imperialism and to spearhead a world socialist revolution.

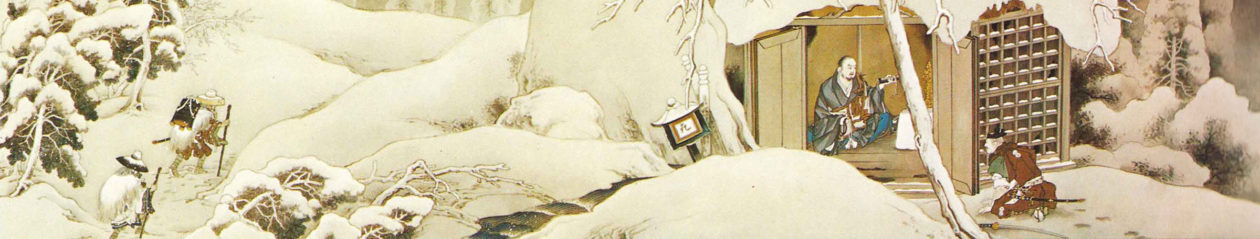

In making this proposal, Kita clearly saw himself as a second Nichiren, remonstrating with government leaders in an attempt to save the country from disaster. Both the Gaishi’s introduction and final chapter—titled “The Mongol Invasion by Britain and Germany,” a reference to European interests in China—speak of the Gaishi as the “Taishō ankoku ron”: Just as Nichiren had risked his life to warn the authorities of foreign invasion in the thirteenth century, Kita now sought to protect the nation by warning against the threat posed by Western imperialism in the Taishō era (1912-26) (1959a, 4, 203). By the 1930s variations on the theme of a Japan-led Pan-Asianism had gained wide support; Kita was among the first to connect it with the new Lotus millennialism.

Kita’s vision also entailed aggressive military conquest culminating in world peace, with Japan presiding over a union of nations. Like Tanaka Chigaku, who may briefly have influenced him, Kita equated Nichiren’s teaching of shakubuku with the forcible extension of empire. The specifically Nichirenist elements in Kita’s vision had less to do with the ideal world that would be achieved under Japanese rule than with the new Nichirenshugi rhetoric of shakubuku as legitimating the violence necessary to accomplish it. The Buddha, Kita said, had manifested himself as the Meiji emperor, and “clasping the eight volumes of the Lotus Sutra of compassion and shakubuku,” waged the Russo-Japanese War. Now China, too, was “clearly thirsting for salvation by shakubuku” (161, 154).

Just as the Lord Śākyamuni [Buddha] prophesied of old, the flag bearing the sun, of the nation of the rising sun, is now truly about to illuminate the darkness of the entire world. … What do I have to hide? I am a disciple of the Lotus Sutra. Nichiren, my elder brother in the teachings, taught the Koran of compassionate shakubuku, but the sword has not been drawn. He preached the doctrine of world unification but it has yet to reach China or India. … Without the Lotus Sutra, China will remain in everlasting darkness; India will in the end be unable to achieve her independence, and Japan too will perish. … Drawing the sword of the Dharma, who in the Final Dharma age will vindicate [the prediction of] Śākyamuni? (201, 203, 204)

… In 1936, leading some fourteen hundred men, [Kita] attempted a coup d’état, assassinating several government officials and seizing the center of Tokyo. … Along with the insurrectionist leaders, Kita was arrested for complicity and executed the following year.