Although the very notion of a “seed” tends to suggest a gradual process of growth and maturation, in Nichiren’s thought, because “original cause” and “original effect” are simultaneous, the “process” of sowing, maturing, and harvesting also occurs simultaneously. This is called, in the terminology of Nichirenshū doctrine, “the seed being simultaneously [the harvest of] liberation” (shu soku datsu). Nichiren explains this idea in readily accessible terms to a lay follower:

The mahā-mandārava flowers in heaven and the cherry blossoms of the human world are both splendid flowers, but the Buddha did not choose them to represent the Lotus Sūtra. There is a reason why, from among all flowers, he chose this [lotus] flower to represent the sūtra. Some flowers first bloom and then produce fruit, while others bear fruit before flowers. Some bear only one blossom but many fruit, others send forth many blossoms but only one fruit, while others produce fruit without flowering. In the case of the lotus, however, flowers and fruit appear at the same time. The merit of all [other] sūtras is uncertain, because they teach that one must first plant good roots and [only] afterward become a Buddha. But in the case of the Lotus Sūtra, when one takes it in one’s hand, that hand at once becomes Buddha, and when one chants it with one’s mouth, that mouth is precisely Buddha. It is like the moon being reflected in the water the moment it appears above the eastern mountains, or like a sound and its echo occurring simultaneously.(Page 271)

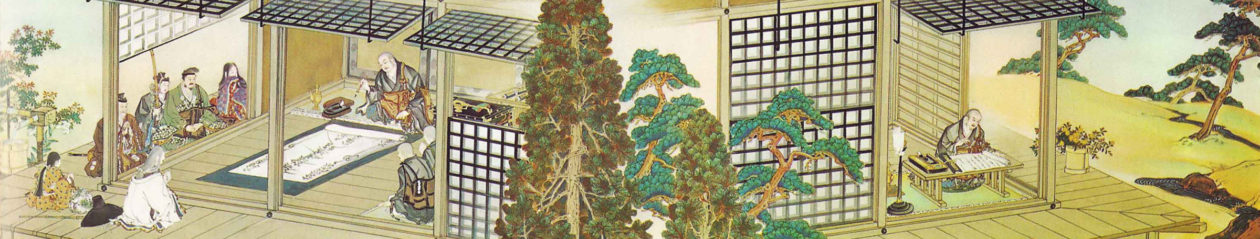

Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism