Two Buddhas, p203-205When Buddhism was transmitted to China, the Mahāyāna concept of all things as empty of fixed, independent existence and therefore mutually interpenetrating and nondual seemed to echo indigenous Chinese notions of a holistic cosmos in which all things are interrelated. This stance proved congenial to early Chinese Buddhist thinkers. But how exactly was the ultimate principle (Ch. li, J. ri) — whether conceptualized as emptiness, mind, or suchness — related to the concrete phenomena or actualities (shi, ji) of our experience? Some teachers conceived of principle in terms of an originally pure and undifferentiated “one mind” that, refracted through deluded perception, gives rise to the phenomenal world, with its distinctions of self and other, true and false, subject and object, good and evil, and so forth. To use a famous metaphor, the mind is originally like still water that accurately mirrors all things. When stirred by the wind of ignorance, waves appear, and the water begins to reflect things in a distorted way, producing the notion of self and other as substantially real entities and thus giving rise to attachment, suffering, and continued rebirth in saṃsāra. Liberation lies in discerning that the differentiated phenomena of the world are in their essence no different from the one mind and thus originally pure. From this perspective, the purpose of Buddhist practice is to dispel delusion and return the mind to its original clarity. This idea developed especially within the Huayan (J. Kegon) and Chan (Zen) traditions.

This model explains principle and phenomena as nondual, but it does not value them equally. The one mind is original, pure, and true, while concrete phenomena are ultimately unreal, arising only as the one mind is filtered through human ignorance. From that perspective, the ordinary elements of daily experience remain at a second-tier level as the epiphenomena of a defiled consciousness. Zhiyi termed this perspective the “realm of the conceivable” — understandable, but not yet adequately expressing the true state of affairs. He himself expressed a different, more subtle view. … [H]e states: “Were the mind to give rise to all phenomena, that would be a vertical [relationship]. Were all phenomena to be simultaneously contained within the mind, that would be a horizontal [relationship]. Neither horizontal nor vertical will do. It is simply that the mind is all phenomena and all phenomena are the mind. … [This relationship] is subtle and profound in the extreme; it can neither be grasped conceptually nor expressed in words. Therefore, it is called the realm of the inconceivable.”

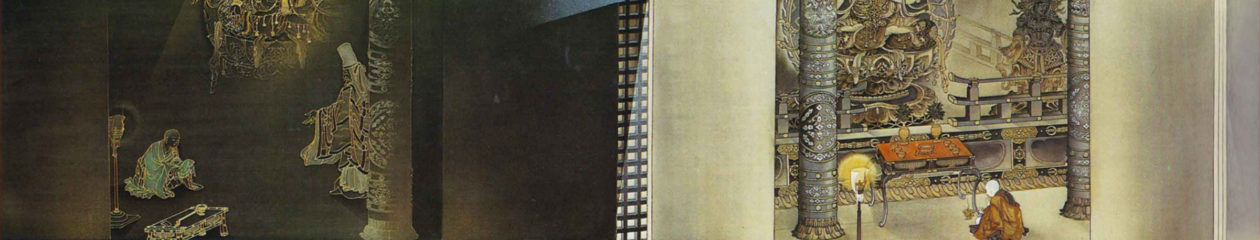

In Zhiyi’s understanding, phenomena do not arise from a pure mind or abstract prior principle. “Principle” means that the material and the mental, subject and object, good and evil, delusion and enlightenment are always nondual and mutually inclusive; this is the “real aspect of all dharmas” that only buddhas can completely know, referred to in the “Skillful Means” chapter (24). This perspective revalorizes the world, not as a realm of delusion, but as the very locus of enlightenment. The aim of practice, then, is not to recover a primal purity, but to manifest the buddha wisdom even amid ignorance and delusion.