In its most specific sense, the place of practice is understood in terms of the “ordination platform of the origin teaching” (honmon no kaidan), the third of the three great secret Dharmas entrusted by the original Śākyamuni to Bodhisattva Superior Conduct for the sake of persons in the Final Dharma age. However, as rules governing conduct, neither the ssu-fen lü precepts nor the bodhisattva precepts receive much attention in Nichiren’s thought. Although he maintained celibacy, refrained from meat-eating, and generally observed the standards of monastic conduct, he described himself as “a monk without precepts.” Like Hōnen, Nichiren saw the Final Dharma age as an age without precepts, when “there is neither keeping the precepts nor breaking them.” From a very early period, he held that “merely to believe in this [Lotus] sūtra is to uphold the precepts,” a statement based on the sūtra’s claim that one who can receive and keep the sūtra after the Buddha’s Nirvāṇa is “a keeper of the precepts.” A later writing explains this in terms of the all-inclusiveness of the daimoku:

Myōhō-renge-kyō, the heart of the origin teaching of the Lotus Sūtra, assembles in five characters all the merit of the myriad practices and good (acts] of the Buddhas of the three time periods. How could these five characters not contain the merit of [upholding] the myriad precepts? After the practitioner has once embraced this perfectly endowed, wonderful precept, it cannot be broken, even if one should try. No doubt this is why it has been called the vajra precept of the jeweled receptacle (kongō hōki kai). By embracing this precept, the Buddhas of the three time periods realized the Dharma, recompense, and manifested bodies, becoming Buddhas without beginning or end. … Because so wonderful a precept has been revealed, the precepts based on the pre-Lotus Sūtra teachings and on the trace teaching are now without the slightest merit.

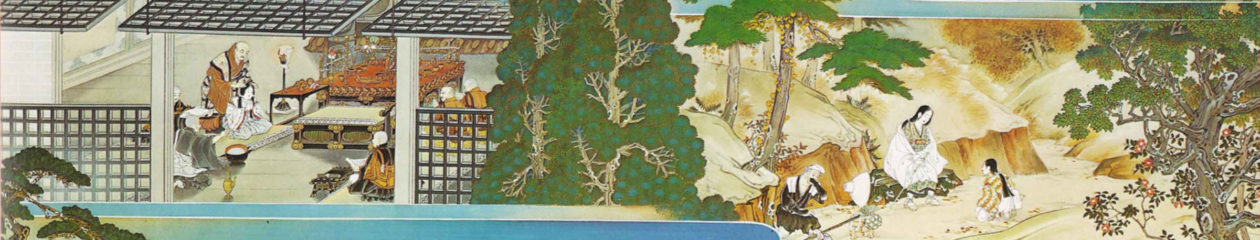

Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism