Daniel Montgomery’s Fire in the Lotus offers many details of the characters who played a role in Nichiren Buddhism. Take the story of Kumarajiva, whose skillful translation of the Lotus Sutra into Chinese led to the sutra’s popularity in Asia.

Kumarajiva was born in Kucha, a Central Asian city on the northern trade route between India and China. His father Kumarayana was an Indian Brahmin of high rank, who had abandoned court life for that of an itinerant preacher. His mother Jiva was a sister of the King of Kucha. When Kumarayana’s travels took him to Kucha, he caused such a sensation that the princess demanded to have him for a husband. Their child was named after both his distinguished parents, Kumara for his father and Jiva for his mother.

Princess Jiva was a most remarkable woman. Under her husband’s influence, she became more and more interested in Buddhism and eventually surpassed him in wisdom and practice. She wanted to become a nun, but her husband objected, at least until a second child was born. When Kumarajiva was seven, his father finally relented. The mother took her son, and both of them entered the Buddhist Order.

When Kumarajiva was nine or ten, he travelled with his mother to India, where they studied under a famous Hinayana teacher. When he was 12, they returned to Central Asia, this time to Kushan, where they continued their studies. Already the boy was known as a precocious scholar and debater. The two spent a year in Kashgar studying Abhidharma (Hinayana philosophy) and other sutras, and then returned to Kucha to study the Hindu Vedas. Finally they were introduced to Mahayana, and Kumarajiva began his career of copying, translating, and lecturing on Mahayana sutras. He became a fully ordained monk, at the age of 20. His mother, who had attained the level of enlightenment called anagamin (one who will never be reborn in this world), retired to India.

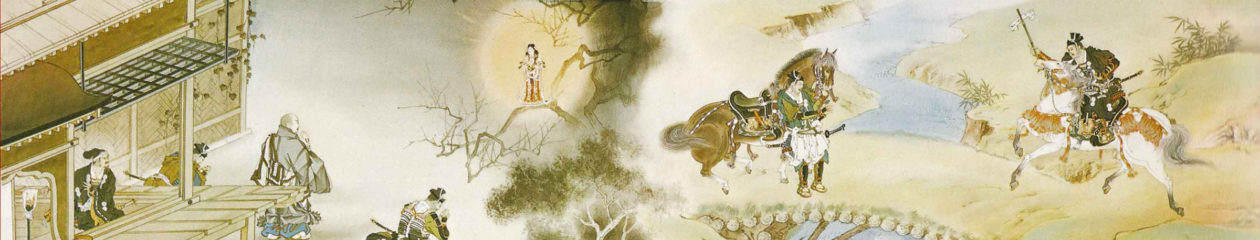

Kumarajiva’s star was still rising. He became the most celebrated teacher in Central Asia, and his fame spread abroad as far as China. King Fu Chien (Fu Jian) of the former Ch’in kingdom resolved to bring him to his capital of Ch’ang-an. Around 382 he sent his general Lu Kuang (Lu Guang) with an army of 70,000 men to capture Kucha and bring back Kumarajiva. It was to be nearly 20 years, however, before Kumarajiva reached China.

General Lu Kuang stormed Kucha, killed the king, and captured the Buddhist sage. However, when he heard bad news from China, that the king had been overthrown and replaced by an inimical monarch, the general decided not to return home. Instead, he returned only part of the way, carved out a petty kingdom of his own, and took his prize captive with him.

The general took perverse delight in humiliating his prisoner. He was not a Buddhist, and was not impressed by Kumarajiva, who was then about 40 years old. He insisted that the monk marry a princess of Kucha. When Kumarajiva refused, the general got him drunk and locked him up in the same room with the princess. By dawn Kumarajiva was no longer either a teetotaler or a virgin.

Kumarajiva, always a scholar at heart, did not waste his time during his long sojourn in western China. He became fluent in the Chinese language, attracted many disciples, and even won the grudging admiration of the general. When the new king of Ch’in (called Later Ch’in), who was a Buddhist, begged the general to send Kumarajiva to China the general refused.

It took a second military invasion to get Kumarajiva into China at last. In 401 an army from China overthrew the general and brought his hostage safely to the capital of Ch’ang-an.

Here the famous teacher was treated with great respect. He was given the title of National Preceptor and put in charge of translating the sutras into Chinese. He was given every facility, including a team of linguists to assist him, and splendid quarters in the royal palace. Under such favorable circumstances he was able to turn out one translation after another, all of them unexcelled in their accuracy and elegant style. The Sutra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma (Myoho Renge-kyo in Sino-Japanese) was his masterpiece.

As Kumarajiva grew older, the king began to fear that his incomparable talent would be lost to the world after his death. The solution seemed to be for him to have an heir, who would carry on his work. He ordered that the sage be waited upon by ten comely maidens, hoping that at least one of them would become the mother of his child. Kumarajiva relented, but he was not proud of his luxurious lifestyle. He is said to have told his pupils, ‘You must take only the lotus flower that grows out of the mire, and not touch the mire itself.’

Many Buddhist monks resented Kumarajiva’s way of life, and a fellow Central Asian, Buddhabhadra, translator of the Flower Garland Sutra, criticized him openly. So popular was Kumarajiva, however, that it was the critic Buddhabhadra who was forced to leave the capital. Kumarajiva continued to live there in splendor until the day he died.

The story is taken from Kogen Mizuno’s “Buddhist Sutras: Origin, Development, Transmission,” which was published by Kosei Publishing in 1989.