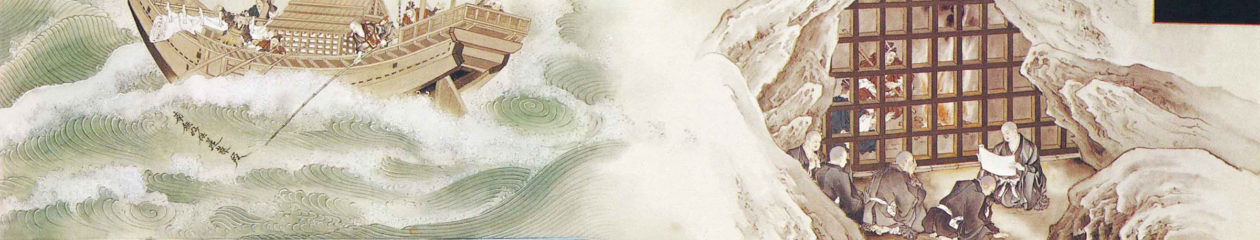

I’m taking a break from my immersion in Risshō Kōsei Kai philosophy and exploring Neal Donner and Daniel B. Stevenson’s “The Great Calming and Contemplations: A Study and Annotated Translation of the First Chapter of Chih-i’s Mo-Ho Chih-Kuan.” I haven’t finished the book yet, but I just couldn’t resist passing on this lesson on “the essential feature about hearing the dharma.”

The quote is from the introduction to the Mo-Ho Chih-Kuan by “Chih-i’s disciple, Kuan-ting (561—632), the man originally responsible for recording and editing the work.” [pxiv]

In former times there was a king who decided not to establish a stable [for his elephants] in the vicinity of a hermitage but placed it instead near a slaughterhouse. How much more likely [than beasts in a stable] are humans, when in the proximity of saints, to benefit from their teachings. Again, a brahmin was selling skulls, of which a rod could be passed clean through some, half through others, and not at all through the remainder. Buddhist laymen built a stūpa for those which the rod passed completely through, performed veneration and made offerings to them, and were consequently reborn in the heavens. The essential feature about hearing the dharma is that it has such merit. It is in order to confer this benefit that the Buddha has transmitted the treasury of the dharma. [p104]

This, of course, is absolutely unintelligible until you read the footnote explanations.

On the topic of the elephant stable:

36. From the Fu fa-tsang yin-yüan chuan, T 50.322a. It seems that a certain king used a fierce elephant to trample criminals to death. A time came when the elephant refused to carry out his task, merely smelling and licking his supposed victims without harming them. On inquiring among his ministers, the king found that the elephant’s stable had recently been moved to the neighborhood of a Buddhist hermitage, and the animal was being influenced by the teachings he heard emanating from the monastery. The king therefore ordered the stable moved to the vicinity of a slaughterhouse, whereupon the elephant soon regained his blood lust.

On the topic of the human skulls:

37. Ibid., T 50.322b. The brāhmin had at first no success in selling the skulls and so became angry, cursing and vilifying those who refused to buy them. The Buddhist laymen of the city were frightened at this and agreed to buy. First, however, they tested the skulls by slipping a rod through the ear holes, saying that they attached the greatest value to those which could be penetrated completely so that the rod came out the other side. They explained that such skulls had belonged to persons who in life had heard the Buddha’s wondrous preaching and had thereby attained great wisdom (literal vacuity of mind). Their veneration of these sacred relics earned them rebirth as devas.

Reading a study of the first chapter of Chih-i’s Mo-Ho Chih-Kuan may sound deadly boring, but I’m having lots of fun.