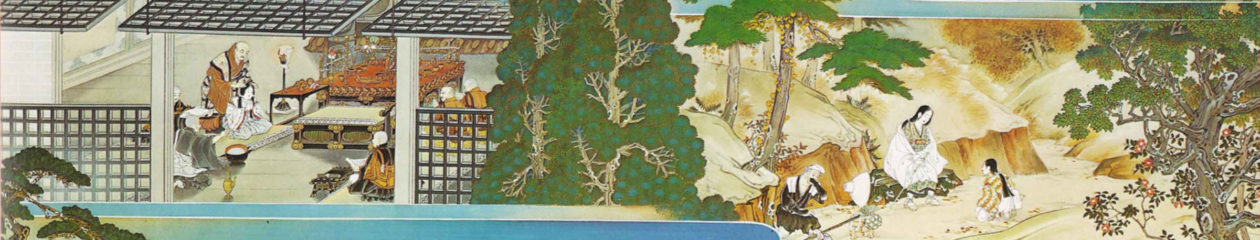

The Karma of Words, p48-49This notion of karma in the Nihon ryōi-ki was closely related to the various modes of salvation that proliferated throughout the medieval period in Japan. The concept of karma and that of the rokudō system provided an answer to one kind of question but also posed, or, at least, exacerbated, an old problem. Like most explanatory systems, the Buddhist one satisfied on one level and disturbed on another. My discussion of the Nihon ryōi-ki up to this point has focused on the way its basic paradigm provided a cognitive explanation of the world’s workings and a way of classifying various kinds of beings both seen and unseen. But it is necessary to recognize that there was also something deeply disquieting about the notion of karma.

As presented in the Nihon ryōi-ki, there is an inexorability in the way karma works: rewards and punishments are exactly equivalent to their corresponding good or bad deeds. Scholars have noted that the work is not necessarily pessimistic, however; Kyōkai is fairly sanguine both about the possibility of evading dire effects and about achieving upward mobility along the six courses. For him it is simply a matter of recognizing the way the system works. Such knowledge, he holds, will change behavior and produce good results. It is, he claims, a matter of “pulling the ears of people over many generations, offering them a hand of encouragement, and showing them how to cleanse the evil from their feet.” Although there are references to Buddhas and bodhisattvas in the work, these do not cancel the karmic results of earlier actions; they are not savior figures in that sense. The author of the Nihon ryōi-ki holds that knowledge of the system will so change behavior that people will move voluntarily and effectively up the ladder of transmigration.

Some of his contemporaries and people of later times were, however, much less sanguine. A satisfying answer to questions concerning the basic functioning of the cosmos did not remove the fears of individuals about their personal destinies. Natural fears vis-a-vis death’s uncertainties were now exacerbated by deep anxiety about the danger of transmigration downward in the taxonomy and a fall into hell. There is abundant evidence that people in all strata of society, fully convinced of the workings of karma, were anxious—perhaps, especially during periods of warfare, when many found themselves killing their fellows in battle.

Unless they were to be in a state of continuing despair, the people of Japan needed to have some relief from the conception of karma and transmigration as exact, inexorable, and unmitigated. They required what has been called rokudō-bakku, or “escape from suffering in the six courses.” In the medieval period, theories of salvation proliferated. Though it would be impossible to survey them all here, each in its own way contributed to the possibility of optimism and hope.