The perpetuation of the Truth

The purpose of Buddha’s work has been laid down, the assurance given to his followers, and the foundation of the Sole Road [One Vehicle] explained. The further revelation naturally turns to how the destiny is to be worked out by the Bodhisattvas. The essence of Bodhisattvaship in this sense consists in the adoration paid to the sacred text of the Lotus, the embodiment of universal truths – adoration not only in worship through ceremonies and recitations, but in practicing its precepts and preaching its truths to others; in short, in living the life of Truth according to the sermons of the Lotus. The Bodhisattva is the messenger of the Tathāgata, the one sent by him, who does the work of the Tathāgata, who puts absolute faith in Buddha and his Truth, and lives the life of Truth, especially by working to propagate the truths of the Lotus among the degenerate people of the Latter Days. [Tathagata (Jap. Nyorai) means the “Truth-winner” and, at the same time, “Truth-revealer.”] Thus, chapter 10, entitled the ” Preacher,” consists of the injunctions given to the Bodhisattvas to live worthy of their high aim and in obedience to Buddha’s message and commission.

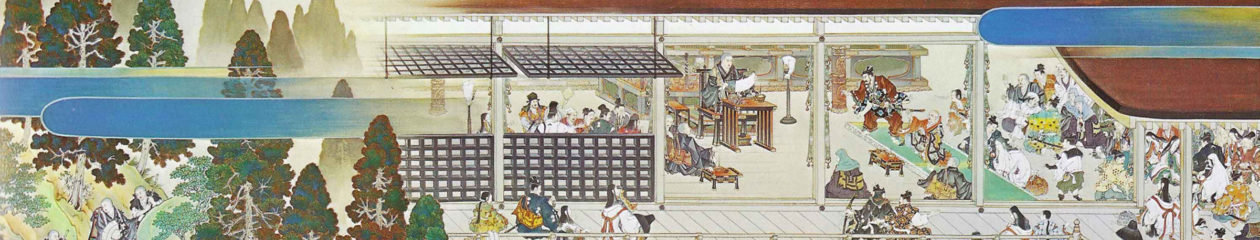

A vision follows the injunction, a miraculous revelation, as well as an apocalyptic assurance (chapter 11, entitled “The Apparition of the Heavenly Shrine”). A vast shrine (stupa) adorned with the seven kinds of jewels appears in front of Śākyamuni as he is preaching; heavenly hosts surround it, waving banners, burning incense, playing music; the air becomes luminous, iridescent, fragrant; the sky resounds with heavenly music and chanted hymns. Suddenly, the scene is totally transformed, as we see in apocalyptic literature generally. A voice is heard from within the shrine in the praise of Śākyamuni’s work and sermons. In the midst of the celestial glories and the hosts of heavenly beings, the Heavenly Shrine is opened, and therein is seen seated the Buddha Prabhūtaratna [Many Treasures, Jap. Tahō], who long since passed away from his earthly manifestation, and has now appeared, to adore Śākyamuni, who is still working in the world. The dramatic situation reaches its climax when the old Buddha invites the present one, and the two sit side by side in the Shrine. The joint proclamation made by them is to prepare the disciples for the approaching end of Śākyamuni’s earthly ministry, and to encourage and stimulate them to the work to be done after the master’s passing away. “Revere the Truth revealed in this holy book, and preach it to others! Anyone who will fulfil this task, so difficult to do, is entitled to attain the Way of Buddha, beyond comparison. He is the child of Buddha, the eyes of the world, and will be praised by all Buddhas.”

The admonition is further encouraged by the prophetic vyākaraṇa [prediction of future Buddhahood] given to Devadatta, the wicked cousin of Buddha, who, because of his long connection with Śākyamuni, will, in spite of his wickedness, attain Buddhahood at a certain future time. Moreover, the assurance of the final perfection is vividly impressed by the instantaneous transformation of a Nāga (Serpent-tribe) [dragon] girl, who now appears as a preacher of the Perfect Truth and one of the Tathāgata’s messengers. The final conversion of the typical wicked man and of the innocent girl indicate that Buddhahood is to be realized by all; and these episodes were always a source of inspiring faith and encouraged trust in the efficacy of the excellent truth revealed in the book.

After the apocalyptic scene and the miraculous conversion, other practical admonitions are given to the future Buddhas. Two ways of spreading the truth are indicated, one the way of vigorous polemic, the repressive and aggressive method of propaganda, and the other the way of pacific self-training, the gentle, persuasive method (chapters 13 and 14, entitled respectively the “Exertion,” or “Perseverance,” and the “Peaceful Training”). The peaceful training in meditation and watchfulness over self was a source of great inspiration to many Buddhists; but greater, at least so far as Nichiren is concerned, was the power inspired by the admonition to perseverance. Indeed, the characteristic feature in Nichiren’s ideal consisted in translating into life the exhortations to strenuous effort, in what he called the ” reading of the Scripture by the bodily life,” which meant actual life, fully in accordance with the truths taught in the book, especially with the exhortations, encouragement, and assurances contained in this chapter on ” Perseverance.” As we shall see later, in every hardship and peril which Nichiren encountered, he derived consolation from Buddha’s reassurance, and stimulating inspiration from the vows uttered by his disciples to sacrifice everything for the sake of the Truth, and to endure perils, sustained by firm belief in the mission of the Tathāgata’s messengers. (“Primeval” is used here and in the sequel of beings, attributes, and relations in a transcendent sphere of reality, in distinction from the world of historical manifestation.)

With these exhortations given to future Buddhas closes the first grand division of the book, which is the revelation of the Sole Road [One Vehicle] proclaimed by Śākyamuni in the “manifestation” aspect of his personality. With the fifteenth chapter opens the revelation of his true, eternal, primeval personality, together with the apparition of his primeval disciples, the vows they take, and the mission entrusted to them.

This thought on the two aspects of Buddha’s personality is a consummate outcome of religious and philosophical speculation on the transient and the everlasting aspects of Buddha’s person and work – a matter touched upon before, when we characterized the book, Lotus, as the Johannine literature of Buddhism. And now, in the last half, is revealed the primeval Buddhahood or the entity and functions of the Buddhist Logos [the active rational and spiritual principle that permeates all reality]. So long as the Buddhists regard their master as a man who achieved Buddhahood at a certain time, they fail to recognize the true person of Buddha, who in reality from eternity has been Buddha, the lord of the world. So long as the vision of Buddhists is thus limited, they are unaware of their own true being, which is as eternal as Buddha’s own primeval nature and attainment. The Truth is eternal, therefore the person who reveals it is also eternal, and the relation between master and disciples is nothing but an original and primeval kinship. This is the fundamental conception, which is further elucidated by showing visions reaching to the eternally past as well as to the everlasting future.

Nichiren's Birth, Studies, and Conversion. The Lotus of Truth

Nichiren's childhood and the years of his study 12

The final resort of his faith and the "Sacred Title" of the Scripture 15

The Lotus of Truth; its general nature 18

The introduction and the exposition of the ideal aim 19

The perpetuation of the Truth 22

The revelation of the real entity of Buddha's personality 26

The "consummation and perpetuation" 29

Nichiren's personal touch with the Scripture 30

NICHIREN: THE BUDDHIST PROPHET