The Collected Teachings of the Tendai Lotus School by Gishin was translated from the Japanese by Paul L. Swanson and published in 1995 as part of the BDK English Tripiṭaka (97-II).

From the Translator’s Introduction

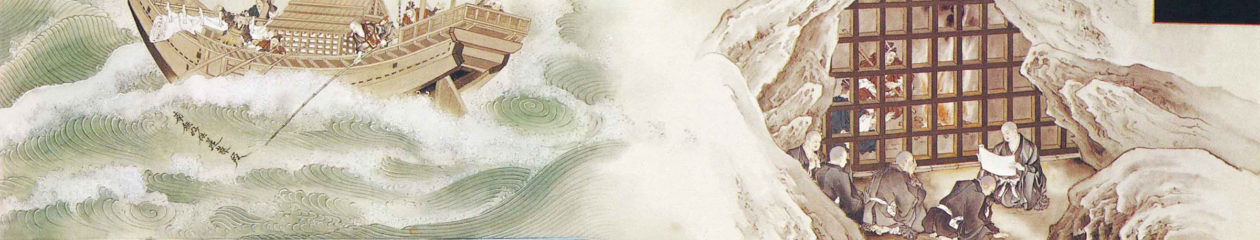

Tendai Lotus School Teachings, p 1-2The Collected Teachings of the Tendai Lotus School (Tendai Hokkeshū Gishū) is an introduction to the doctrine and practice of the Japanese Tendai school. It was compiled by Gishin (781-833), the monk who accompanied Saichō (767-822) to T’ang China as his interpreter, so that he might help to transmit the Chinese T’ien-t’ai tradition to Japan. He later succeeded Saichō as head of the Tendai establishment on Mt. Hiei. The content of this work consists, for the most part, of extracts from the writings of Chih-i (538-97), the founder of Chinese T’ien-t’ai Buddhism; and it concisely outlines the basic tenets of Tendai doctrine and practice. Except for the introduction and colophon, it takes the form of a catechism. It is divided into two major sections, on doctrine and on practice. The section on doctrine contains a discussion of the Four Teachings, the Five Flavors, the One Vehicle, the Ten Suchlikes, Twelvefold Conditioned Co-arising, and the Two Truths. The section on practice discusses the Four Samādhis and the Three Categories of Delusions.

The Collected Teachings of the Tendai Lotus School was compiled in response to an imperial request that each Buddhist school prepare a description and defense of its own doctrine for submission to the court. The resulting texts are often referred to as “The Six Sectarian Texts Compiled by Imperial Request in the Tenchō. …

The exact date of compilation of this present work is uncertain. The Tendai zasu ki, an ecclesiastical history of the Tendai prelates, claims that Gishin compiled it in 823; but the closing verse in the Collected Teachings itself mentions the Tenchō era (824-34). It was probably submitted to the court in 830 along with the other five works.

The Collected Teachings of the Tendai Lotus School is the shortest of the works submitted to the court by the six Buddhist schools. … Its content is limited to Tendai proper and does not discuss esoteric Buddhism, Zen, or precepts, the other three of the so-called “four pillars of Japanese Tendai.” This was the cause of some controversy, since it ignored both esoteric Buddhism, which was in such great demand at the time, and the important issue of Hinayāna vs. Mahāyāna precepts. Perhaps Gishin felt that a straightforward presentation of the unique features of Tendai proper, as presented in the writings of Chih-i, was most important. Thus the final incorporation of esoteric Buddhism into Japanese Tendai was left to later monks such as Ennin (794-864), Enchin (814-89), and Annen (841-?).

At the conclusion of the Preface, Gishin writes:

Tendai Lotus School Teachings, p 7This compilation first presents the two main topics, Doctrine and Contemplation. Next, under these categories it lists all the essential points and outlines them. However, the doctrine is vast, so that shallow and ignorant people become lost. Mysterious reality is deep and profound, so that fools cannot measure it. It is like scooping up the ocean with a broken gourd or viewing the heavens with a tiny tube. Therefore I clumsily take up this great rope [of the vast Buddha-dharma] and feebly attempt to compose this work. At times the text is brief and the meaning hidden, at times [it is] short or long. If one tried to exhaust all the details, the result would be too complicated. As an incomplete presentation of the essentials of our school, it resembles a crude commentary. The attempts at summation often miss the mark, and the essential content is difficult to outline.

The reason that the Four Teachings and the Five Flavors stand at the beginning is that these are the fundamental doctrines of the original Buddha and the basis of this [Tendai] school’s profound teaching. The other doctrines are numerous, but they depend on and proceed from these first two. This work consists of one fascicle and is called The Collected Teachings of the Tendai Lotus School.

At the end, Gishin offers this verse:

In praise it is said:

After Kuśināgara [where the Buddha entered final Nirvāṇa] ,

In the midst of the era of the semblance Dharma,

The two sages of Mt. Nan-yo and Mt. T’ien-t’ai

And the two leaders Chan-jan and Saichō

Firmly established the Path for the myriad years,

And its doctrine crowned all schools.In the Tenchō period (824-834) Buddhism again flourished.

The Emperor mercifully requested

A presentation of the admirable [doctrines].

Therefore, of the luxuriant meanings

I have outlined just a few.

Tendai Lotus School Teachings, p 136

The text translated by Swanson was actually copied in the middle of the winter of 1649 by “an anonymous private monk”:

Colophon

Tendai Lotus School Teachings, p 137The Collected Teachings is a composition by Master [Gi]shin of Mt. Hiei. Whether on teachings or on the practice of contemplation, it is an outline of the 80,000 doctrines in the twelvefold scripture, a summary of the essentials concerning all the subjects of this [Tendai] school, rolled up in many pages. It should be recognized as a substantial vessel of scholarship. It is also a book that has reached the attention of the Emperor. It has already been officially presented to the court. How can it not be transmitted? In the past it was popular, but it became old with the years. Since there are not a few errata [in the text], I am now correcting and editing it, adding punctuation, having catalpa wood plates carved, and bringing it to print. It is hoped that this work by such a virtuous elder will not disappear for a thousand years.

See Tendai Lotus Teachings and Nichiren