The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p304-305In the Chapter 28 story, Universal Sage Bodhisattva promises that if anyone accepts and upholds the Dharma Flower Sutra he will come to that person mounted on a white elephant with six tusks. This can be understood to mean that taking the Sutra seriously gives one extraordinary strength or power. The elephant itself is often a symbol of strength or power, the whiteness of the elephant has been taken to symbolize purity, and the six tusks have been taken to represent both the six paramitas or transcendental bodhisattva practices and purification of the six senses. But if the elephant is taken to be a symbol of power, we should understand that this is not a power to do just anything. It is a power to practice the Dharma, strength to do the Buddha’s work in the world, power to be a universal sage.

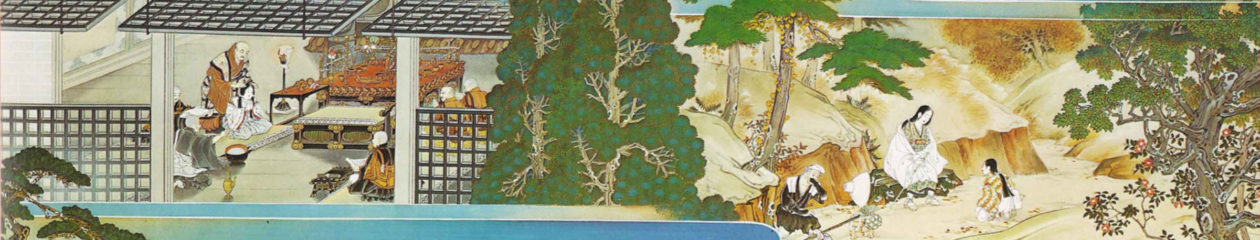

Though the image does not come from this story but from the much more involved visualization of the Sutra of Meditation on the Dharma Practice of Universal Sage Bodhisattva, the elephant on which Universal Sage Bodhisattva rides is very often depicted as either walking on blossoming lotus flowers or wearing them like shoes. If the elephant is not standing, a lotus flower will be under the foot of Universal Sage. Such lotus blossoming should be understood, I believe, as an attempt to depict in a motionless picture or statue something that is actually very dynamic – the flowering of the Dharma.

Category Archives: stories

We All Need Good Friends and Teachers

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p289King Wonderfully Adorned praises his sons, calling them his friends or teachers, and Wisdom Blessed Buddha responds that good friends or teachers do the work of the Buddha, showing people the Way, causing them to enter it, and bringing them joy.

The term used here, zenchishiki in Japanese, is not easy to translate. Some use “good friends,” some “good teachers.” Perhaps good “acquaintances” or “associates” would be a good translation, for there is a sense in which our good friends are always also our teachers. The point is that the help or guidance of others can be enormously useful. Entering the Way, becoming more mindful or awakened, is not something best done in isolation. We all need good friends and teachers.

The Bodhisattva Model

Of course, those who would follow the bodhisattva way should see great bodhisattvas as models for us and not be looking to gods or goddesses for special favors.

A Chinese poem of unknown origins says:

The Dharma-body of Kwan-yin

Is neither male nor female.

If even the body is not the body,

What attributes can there be? …’

Let it be known to all Buddhists:

Do not cling to form.

The bodhisattva is you:

Not the picture or the image.

Our Extraordinary Ability to Serve Others

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p263-264In [Chapter 23] of the Sutra, about the previous lives of Medicine King Bodhisattva, it is said that Seen with Joy by All the Living Bodhisattva attained a concentration that enabled him to take on any form. It was gaining the ability to take on any form that led this bodhisattva to sacrifice his body to the Buddha of his world. But in Chapter 23 we are not told what the name of this concentration means. Here, in Chapter 24, we can see more clearly what this ability to take on any form is about. It is an extraordinary ability to serve others.

Then the Buddha tells Flower Virtue that while he can see only one body of Wonderful Voice Bodhisattva, this bodhisattva appears in many different bodies, everywhere teaching this Sutra for the sake of the living. He appears as the king Brahma, as Indra, Ishvara or Maha-Ishvara, or as a great general of heaven. Sometimes he appears as Vaishravana, or as a holy wheel-rolling king, or as a lesser king; or he appears as an elder, an ordinary citizen, a high official, a brahman, or a monk, nun, layman, or laywoman; or he appears as the wife of an elder or householder, the wife of a high official, or the wife of a brahman, or as a boy or girl; or he appears as a god, a dragon, satyr, centaur, ashura, griffin, chimera, python, human or nonhuman being, and so on. He can help those who are in a purgatory, or are hungry spirits or animals, and all who are in difficult circumstances. And for the sake of those in the king’s harem he transforms himself into a woman and teaches this Sutra.

For those who need the form of a shravaka, a pratyekabuddha, or a bodhisattva to be liberated, he appears in the form of a shravaka, pratyekabuddha, or bodhisattva and teaches the Dharma. For those who need the form of a buddha to be liberated, he appears in the form of a buddha and teaches the Dharma. According to what is needed for liberation, he appears in various forms. Even if it is appropriate to enter extinction for the sake of liberation, he shows himself as one who enters extinction. (LS 367—68)

This variety of forms is remarkably inclusive. While clearly advocating and emphasizing the importance of the bodhisattva way, the Dharma Flower Sutra wants its hearers and readers to understand that appearing in the form of a bodhisattva is only one way among many, any of which can be effective. This variety of forms can be seen as an expression of the emphasis found in the first few chapters of the Sutra on the variety of skillful means. But here, in a sense, the message is even more direct. If, it says, you are “the wife of a brahman,” or “a boy or girl,” or anyone else, you too can be a bodhisattva, you can be Wonderful Voice Bodhisattva!

The Deeper Meaning Beneath the Burning Question

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p246Despite the fact that this chapter is taken by some as praising the actual sacrifice of one’s body or body parts by burning, I believe that the Lotus Sutra does not teach that we should burn ourselves or parts of our bodies. The idea that keeping even a single verse of the Lotus Sutra is more rewarding than burning one’s finger or toe suggests this. And further, suicide would go against the teachings of the Sutra as a whole as well as the Buddha’s precept against killing. The language here, as in so much of the Lotus Sutra, is symbolic, carrying a deeper meaning than what appears on the surface.

Bodhisattva Practice Begins with Respecting Others

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p216-216Teachers of the Lotus Sutra often say that it teaches the bodhisattva way of helping others. Unfortunately, this is sometimes understood to mean intruding where one is not wanted, interfering with the lives of others, in order to “do good.” But the story of Never Disrespectful Bodhisattva may lead us to see that doing good for others begins with respecting them, seeing the buddha in them. If we sincerely look for the potential in someone else to be a buddha, rather than criticizing or complaining about negative factors, we will be encouraged by the positive things that we surely will find. And furthermore, by looking for the good in others, we can come to have a more positive attitude ourselves and thus move along our own bodhisattva path.

In earlier chapters of the Lotus Sutra, it is the Buddha who is able to see the potential to become a buddha in others. But here it becomes very clear that seeing the buddha or the buddha-potential in others is something we all should practice, both for the good of others and for our own good.

Invitation to Creative Wisdom

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p23What is the purpose of all this enchantment and magic? Entertainment? In one sense, yes! It is to bring joy to the world. Stories are for enjoyment. But not only for enjoyment. Not in all of them, but in a great many of the stories in the Lotus Sutra, especially in those that are used to demonstrate practice of skillful means, it is important to recognize that what is being demanded of the reader is not obedience to any formula or code or book, not even to the Lotus Sutra, but imaginative and creative approaches to concrete problems. A father gets his children out of a burning house, another helps his long-lost adult son gain self-respect and confidence through skillful use of psychology, still another father pretends to be dead as a way of shocking his children into taking a good medicine he had prepared for them, and a rich man tries to relieve his friend’s poverty. These stories all involve finding creative solutions to quite ordinary problems.

Creativity requires imagination, the ability to see possibilities where others see only what is. It is, in a sense, an ability to see beyond the facts, to see beyond the way things are, to envision something new. Of course, it is not only imagination that is required to overcome problems. Wisdom, or intelligence, and compassion are also needed. But it is very interesting that the problems encountered by the buddha figures in the parables of the Lotus Sutra are never solved by the book. They do not pull out a sutra to find a solution to the problem confronting them. In every case, something new, something creative, is attempted; something from the creative imagination.

A Radical Affirmation of This World

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p190-191That the bodhisattvas are from the earth has traditionally been taken to be an affirmation of this world, usually called the “saha world” in the Sanskrit Saddharma-pundarika Sutra. That it is the saha world means that this world is the world in which suffering both must be and can be endured. There is a pattern in the Dharma Flower Sutra in which some great cosmic and supernatural event demonstrates or testifies to the cosmic importance of Shakyamuni Buddha, and, since Shakyamuni is uniquely associated with this world, its reality and importance is also affirmed in this way; and, since what Shakyamuni primarily gives to this world according to the Sutra is the Dharma Flower Sutra itself, it too is very special and important; and, since the Dharma Flower Sutra is not the Dharma Flower Sutra unless it is read and embraced by someone, the importance of the life of the hearer or reader of the Sutra is also affirmed; and, since the most appropriate way of life for a follower of the Dharma Flower Sutra is the bodhisattva way, it too is elevated and affirmed. These five – Shakyamuni Buddha, this world, the Dharma Flower Sutra, the hearer or reader of the Sutra, and the bodhisattva way – do not have to appear in this particular order. Any one of them leads to an affirmation of the others. But there is a pattern in the Dharma Flower Sutra, wherein there is a radical affirmation of this world, this world of suffering, but an affirmation that is necessarily linked to the importance of Shakyamuni Buddha and the Dharma Flower Sutra on the one hand and to the lives and bodhisattva practices of those who embrace the Sutra on the other.

Thus, we can say that to truly love and follow the Buddha is also to love and care for the world, which is also to love and care for other living beings. And the reverse is equally true: to really care for others is at the same time devotion to the Buddha. To be devoted to the Dharma Flower Sutra and to Shakyamuni Buddha is to be vitally concerned about the welfare of others, the common good, and therefore about the welfare of our home, the earth.

The Real Superiority of this Sutra Lies in Its Comprehensiveness

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p181-182The final verse portion of the chapter says that the Buddha has taught many sutras as skillful means, and when he knows that people have gained sufficient strength from them, he at last and for their sake teaches the Dharma Flower Sutra. In other words, it is because other sutras have been taught and people have gained strength from them that the Buddha is at last able to teach the Dharma Flower Sutra. Other sutras and teachings prepare and open the way for the teachings of the Dharma Flower Sutra.

This means, of course, that while followers of the Dharma Flower Sutra may think it is the greatest of sutras, they should not disparage other sutras or other teachings, just as is taught in the four trouble-free practices in the early part of the chapter.

Yet in what way is the Lotus Sutra superior to or better than other sutras? In this story, this is not explicit, but if we look below the surface, we may find an answer to this question.

The jewel in the topknot is very valuable, but we are not told in what way it is more valuable than other valuable things. The text says that the Dharma Flower Sutra is “supreme,” the “greatest,” the “most profound,” the “highest.” But there are only a couple of hints or suggestions as to how it is supreme among sutras. One hint is that the Sutra, like the jewel in the topknot, is withheld to the last. But, surely, merely being last is not necessarily a great virtue and would not automatically make this Sutra any better than any other. The second thing we are told is that the Dharma Flower Sutra “can lead all the living to comprehensive wisdom.” Thus, we may think, the reason that being last is important in this case is because being last makes it possible for the Dharma Flower Sutra to take account of what has come before and be more inclusive than earlier sutras. While much use is made here of what are basically spatial metaphors, such as highest, or most profound, what is suggested here is that the real superiority of this Sutra lies in its comprehensiveness. And this is not so much a matter of repeating doctrine and ideas found in earlier sutras as it is a matter of having a positive regard both for the earlier sutras and for those who teach or follow them, and thus being more comprehensive.

This is why three of the four practices urged on bodhisattvas at the beginning of the chapter involve having a generous, respectful, positive, helpful attitude toward others. Rather than reject other teachings and sutras, the Dharma Flower Sutra teaches that all sutras should be regarded as potentially leading to the larger, more comprehensive, more inclusive wisdom of the Lotus Sutra itself.

The Stories of Devadatta and the Dragon Princess

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p147In Chinese and Japanese versions of the Lotus Sutra and in translations from Chinese, the stories of Devadatta and the dragon princess comprise Chapter 12, while in Indian versions they appear at the end of the previous chapter. This gives a stronger impression of the chapter being an interruption of the longer story that begins in Chapter 11 with the emergence from the ground of the Stupa of Abundant Treasures Buddha. Originally these two stories may have circulated independently of the Lotus Sutra as one or two different texts. Putting them in a separate chapter in this way gives more emphasis and importance to them.

Superficially there is not much reason for these two stories to be together. In terms of characters, they have nothing in common. What makes sense – both in terms of their being together in one chapter and of the chapter being inserted at this point in the Sutra – is the teaching of universal awakening found throughout the Lotus Sutra. The chapter reinforces the idea that there can be no exception to the teaching that everyone is to some degree on the bodhisattva path to becoming a buddha – including those regarded as evil, and even women, who too often in India were regarded as inherently evil.