The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p22-23It is quite possible to study the Dharma Flower Sutra by focusing on its teachings, perhaps using its parables and stories to illustrate those teachings. But by focusing on the stories, we will discover some things that we could not see by focusing on teachings.

In many ways the Dharma Flower Sutra is a difficult book that stretches beyond, and sometimes even makes fun of, the tradition in which it lives. It surprises. But it does so primarily in its stories, which force us to think, for example, about what it means to tell the truth, or what it means to be a bodhisattva or a buddha. And its stories call for, elicit, a creative response from the hearer or reader.

Category Archives: stories

Episodes in a Great Story

As we have it now, the first twenty-two chapters of the Sutra, except for Chapter 12, constitute a single story, a story about a time when the Buddha was at the place called Holy Eagle Peak and preached the Dharma Flower Sutra. In other words, about 85 percent of the Sutra falls within a single story.

Thus while there are many stories in the Lotus Sutra, many of them are actually episodes within a larger story that begins with Chapter 1 as a kind of introduction and continues through Chapter 22, which provides a natural end for the Sutra, as well as to the story that begins in the first chapter. Chapter 12 is inserted in order to emphasize the universality of the buddha-nature, and Chapters 23 through 28 are added, for the most part, as illustrations of bodhisattva practice.

20

An Invitation and a Warning

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p25-26Creativity is a path to liberation, and imagination is a path to liberation. That is why the Dharma Flower Sutra invites us into a world of enchantment – to enable us to enter the path of liberation, a liberation that is always both for ourselves and for others. Notice, please, that this first chapter of the Lotus Sutra does not come to us as an order; it is an invitation to enter a new world and thereby take up a new life, but it is only an invitation.

But this invitation also carries a warning – enter this world and your life may be changed. It may be changed in ways you never expected. The Dharma Flower Sutra comes with a warning label. Instead of saying “Dangerous to your health,” it says, “Dangerous to your comfort.” The worst sin in the Lotus Sutra is complacency and the arrogance of thinking one has arrived and has no more to do. The Sutra challenges such comfort and comfortable ideas. Danger can be exciting. It can also be frightening. We do not know if we can make it. We do not know whether we even have the power to enter the path, the Buddha Way.

This is why, while the Dharma Flower Sutra begins with enchantment, it does not end there. It goes further to announce that each and every one of us has within us a great and marvelous power, later called “buddha-nature.” The term “buddha-nature” does not appear in the Lotus Sutra, probably because it had not yet been invented, but the idea that would later be called “buddha-nature” runs through these stories not as a mere thread, but as a central pillar – albeit a very flexible one.

Compassion, Wisdom and Action

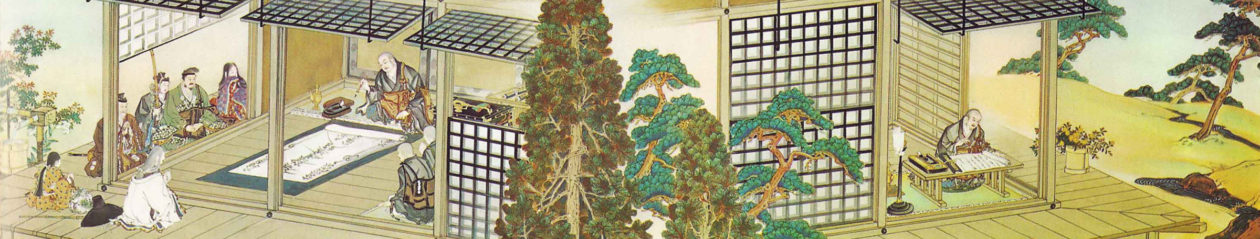

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p298-299In East Asian Buddhist temples and art one can find portrayals of many different bodhisattvas, but only five are found over and over again, in nearly all temples and museums. Their Indian names are Avalokiteshvara, Maitreya, Manjushri, Kshitigarbha, and Samantabhadra. In English they commonly called Kwan-yin (from Chinese), Maitreya, Manjushri (both from Sanskrit), Jizo (from Japanese), and Universal Sage. All except Jizo are prominent in the Lotus Sutra, though in different ways. While both Kwan-yin and Universal Sage have entire chapters devoted to them, except for a mention of Kwan-yin as present in the great assembly of Chapter 1, they do not otherwise appear in the rest of the text, while Manjushri and Maitreya appear often throughout the Sutra. In typical Chinese Buddhist temples, where the central figure is a buddha or buddhas, to the right one can see a statue of Manjushri mounted on a lion, and to the left Universal Sage riding on an elephant, usually a white elephant with six tusks.

While both Kwan-yin and Maitreya are said to symbolize compassion and Manjushri usually symbolizes wisdom, Universal Sage is often used to symbolize awakened action, embodying wisdom and compassion in everyday life. Above the main entrance to Rissho Kosei-kai’s Great Sacred Hall, for instance, there is a wonderful set of paintings depicting Manjushri and wisdom on the right, Maitreya and compassion on the left, and in the middle, the embodiment of these in life – Universal Sage Bodhisattva.

The Role of Pratyekabuddhas

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p289-290In the Lotus Sutra, the term pratyekabuddha is used to refer to monks who go off into forests by themselves to pursue their own awakening in solitude. But while the term is used frequently in the early chapters and pratyekabuddhas are made prominent by being named as one of the four holy states of buddhas, bodhisattvas, pratyekabuddhas, and shravakas, we never learn anything at all about any particular pratyekabuddha. While we hear the names of a great many buddhas, bodhisattvas, and shravakas in the Lotus Sutra, we never encounter the name of even a single pratyekabuddha. This leads me to think that, at least for the Lotus Sutra, pratyekabuddhas are not very important.

Though there probably was a historic forest-monk tradition in India, in the Lotus Sutra the pratyekabuddha seems to fill a kind of logical role. That is, there are those who strive for awakening primarily in monastic communities, the shravakas, and there are those who strive for awakening in ordinary communities, the bodhisattvas. There needs to be room for those who strive for awakening apart from all communities – the pratyekabuddhas. But from the bodhisattva perspective of the Dharma Flower Sutra, pratyekabuddhas are in a sense irrelevant. Since they do not even teach others, they indeed do no harm, but neither do they contribute to the Buddha’s work of transforming the world into a buddha land.

The Compassionate Action of Bodhisattvas

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p275-276Buddhism, perhaps especially Indian Buddhism, was closely associated with the goal of “supreme awakening,” and therefore with a kind of wisdom, especially a kind of wisdom in which doctrines and teachings are most important. Even the term for Buddhism in Chinese and Japanese means “Buddhist teaching.”

With the development of Kwan-yin devotion, while wisdom remained important, compassion came to play a larger role in the relative status of Buddhist virtues, especially among illiterate common people. Thus, there was a slight shift in the meaning of the “bodhisattva way.” From being primarily a way toward an enlightened mind, it became primarily the way of compassionate action to save others.

The Dharma Flower Sutra itself, I believe, can be used to support the primacy of either wisdom or compassion. When it is teaching in a straightforward way, the emphasis is on teaching the Dharma as the most effective way of helping or saving others. But, taken collectively, the parables of the Dharma Flower Sutra suggest a different emphasis. The father of the children in the burning house does not teach the children how to cope with fire; he gets them out of the house. The father of the long-lost, poor son does not so much teach him in ordinary ways as he does by example and, especially, by giving him encouragement. The guide who conjures up a fantastic city for weary travelers does not teach by giving them doctrines for coping with a difficult situation; instead, he gives them a place in which to rest, enabling them to go on. The doctor with the children who have taken poison tries to teach them to take some good medicine but fails and resorts instead to shocking them by announcing his own death. All of these actions require, of course, considerable intelligence or wisdom. But what is emphasized is that they are done by people moved by compassion to benefit others.

The Voice of Wonderful Voice

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p260Here [in Chapter 24] it might be relevant to remember that this display of light by Shakyamuni Buddha has happened in Chapter 1. There we learn that it has happened many times in the past, always signifying that the Buddha was about to preach the Dharma Flower Sutra. Should we assume that this meaning has simply been forgotten here? Or might it be the case that in the story of Wonderful Voice Bodhisattva the Dharma Flower Sutra is being preached in some way? But here its teaching is seen not so much as something oral or written, but as a kind of action. That is, Wonderful Voice Bodhisattva can be understood to be preaching or teaching the Dharma Flower Sutra not so much by words as by embodying it by taking on whatever forms are needed to help others. The voice of Wonderful Voice then, is wonderful not by being loud or beautiful but by being absent! His voice, in a sense, is his body, which takes on whatever form is needed by others.

The Most Important Meaning of ‘Burning Our bodies’

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p247[W]e should devote our whole selves to the Dharma, to the Truth. This is the most important meaning of “burning our bodies.” Does it mean abandoning the bodhisattva practice of service to others in order to serve the Dharma? Of course not. It is by serving the Dharma that we serve both others and ourselves. Serving the Dharma and serving others cannot be separated, just as serving others cannot be completely separated from serving ourselves. This integration of interests – in contrast with Western individualism and with certain Christian ideas of completely selfless devotion and sacrifice – is one of the great insights of Buddhism.

Let your practice be a light for others, helping them to dispel the darkness. This is a second symbolic meaning of “burning” our bodies or arms.

Our Field of Bodhisattva Practice

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p192It is quite revealing that the Buddha declines the offer of bodhisattvas from other worlds to help in this world. It indicates that we who live in this world have to be responsible for our own world. We can rely neither on gods nor extraterrestrial beings of any kind to fulfill our responsibilities. In recent years we have experienced extremely severe “natural calamities” all over the world. No doubt some of these were unavoidable, but almost certainly some were related to the warming trend of the earth’s climate, which results directly from human activity, from releasing greater and greater quantities of carbon dioxide into the earth’s atmosphere. Some potential disasters can be avoided if we realize that this is the only home we or our descendants will ever have and begin to take better care of it.

Of course, the authors and compilers of the Dharma Flower Sutra had no idea of modern environmental issues such as global warming. Still, they did have a very keen sense of the importance of this world as the home both of Shakyamuni and of themselves. They too thought that what we human beings do with our lives, how we live on this earth, is of the utmost importance.

Thus, this story is not only about affirmation of the earth. As is always the case when a text is read religiously, it is also about ourselves, in this case, the hearers or readers of the Dharma Flower Sutra. It tells us who we are – namely, people with responsibilities for this world and what it will become, people who are encouraged to follow the bodhisattva way toward being a buddha, people for whom, like Shakyamuni Buddha, this world of suffering is our world, our field of bodhisattva practice.

The Relation Between true Dharma and merely formal Dharma

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p 217-218The relation between sincere respect and its expressions in gestures and words is something like the relation between true Dharma and merely formal Dharma. And yet expressions of respect even when respect is not sincerely felt can still be good. What we can think of as ritual politeness – saying “Thank you” when receiving something, even if we do not feel grateful; asking “How are you?” when greeting someone and not even waiting for a response; saying “I’m sorry” when we do not really feel sorry – can all contribute to smoother social relations. Just as true Dharma is greater than merely formal Dharma, being truly grateful is greater than expressing gratitude in a merely formal way, and heartfelt sincerity is greater than merely conventional politeness, but even social conventions and polite expressions can be an important ingredient in relations between people and can contribute to mutual harmony and respect.

When we bow in respect before a buddha image, is it an expression of deep respect or merely a habit? When the object of our sutra recitation is to get to the end as quickly as possible or to demonstrate skill in reading rapidly, is our recitation anything more than a formality?

When we take a moment to pray with others for world peace, are we expressing a profound aspiration for world peace, an aspiration that is bound to lead to appropriate actions, or are we simply conforming to social expectations? Probably in most cases, the truth lies somewhere in the middle, where our gestures and expressions are neither deeply felt nor completely superficial and empty. It is possible, after all, to be a little sincere or a little grateful. We should, of course, try to become more and more genuinely grateful and sincere, but we should not disparage those important social conventions, often different in different cultures, found in one way or another in virtually all cultures.