Stone: Seeking Enlightenment in the Last Age, p29 of Part 1Buddhist tradition maintains that as the world moves farther and farther away from the age of Shakyamuni Buddha, understanding of his teachings grows increasingly distorted and people’s capacity to practice and benefit from those teachings accordingly declines, until eventually Buddhism is lost. Sutras and treatises divide this process of degeneration into three sequential periods beginning from the time of the Buddha’s death: the age of the True Dharma (Skt. saddharma, Jap. shōbō) the age of the Counterfeit Dharma (saddharma-pratirūpaka, zōhō) and the age of the Final Dharma (saddharma-vipralopa, mappō).

Stone: Seeking Enlightenment in the Last Age, p33 of Part 1Ta-Chi-Ching, the Great Collection Sutra, contains three periods and divides the decline into five consecutive 500-year periods. The fifth 500-year period is the age when “quarrels and disputes will arise among the adherents to my [Shakyamuni’s] teachings, and the Pre Dharma will be obscured and lost.” The “True” and “Counterfeit” ages each last 1,000 years and the “Final Dharma” age was said to last 10,000 years, which also meant an indefinite period.

This was true as far as Buddhism of Kamakura Japan was concerned.

In 1991, however, Jan Nattier, a PhD graduate of Harvard University, published “Once Upon A future Time: Studies in a Buddhist Prophecy of Decline,” which was based on her doctoral thesis delivered in 1988. In her book, Nattier clearly shows that the concept of three ages of decline and especially the last age, mappō, were the product of Chinese commentators and not the product of Indian Buddhism.

But mappō was very real for Buddhists of Japan.

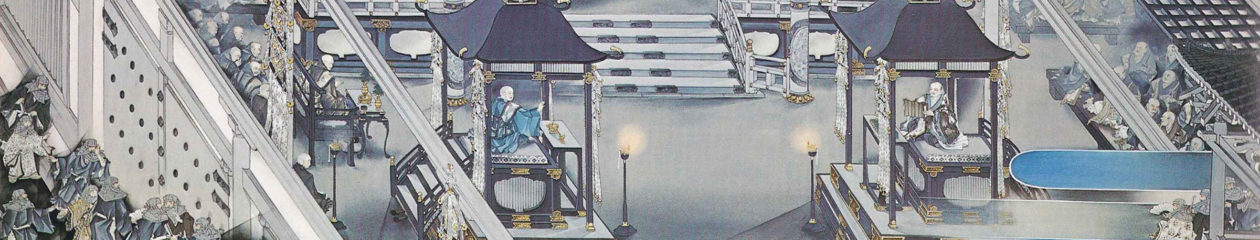

Stone: Seeking Enlightenment in the Last Age, p28 of Part 1By the latter part of the Heian Period (794-1185), a majority of Japanese believed that the world had entered a dark era known as mappō the age of the Final Dharma. Buddhist tradition held that in this age, owing to human depravity, the teachings of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni would become obscured, and enlightenment all but impossible to attain. By the mid-eleventh century, natural disasters, social instability and widespread corruption among the Buddhist clergy lent seeming credence to scriptural predictions about the evil age of mappō —predictions which in turn gave form to popular anxieties, feeding the growing mood of terror, despair and anomie known as mappō consciousness.

Stone: Seeking Enlightenment in the Last Age, p62 of Part 2The idea of mappō involves not only the decline of the world—as suggested by the “five defilements”—but the failure of the means of salvation itself. At a time when the bodies of plague victims periodically littered the streets, when fires and earthquakes leveled temples and government offices alike, when warrior clans rose to challenge a tottering nobility in a series of bloody altercations that radically altered the political structure, Japanese on the whole must have come to realize the uncertainty of this world with an immediacy that people but rarely experience under more tranquil conditions. The prediction that in this hour, Buddhism too would decline must have filled them with a horror beyond imagining.