The Buddha’s teaching is spoken of in five periods, and these five periods are tantamount to the five flavors of dairy products: milk, cream, curdled milk, butter and ghee. The teaching of the Buddha in the five periods is classified into three types: Sudden (Tun), Gradual (Chien), and Indeterminate (Pu-ting).

5.l.1 Classifying the teaching of the Buddha in terms of the Five periods

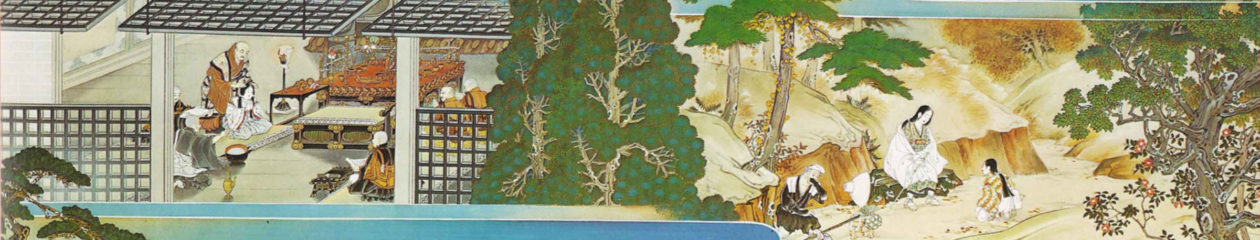

The first period that is compared with “when the sun rises, it first shines on the highest mountains, is defined as “Sudden” (Tun), and is analogous with the flavor of milk. It is called “Sudden,” because the teaching in this period carries the profound truth (that has been perceived by the Buddha upon his enlightenment under the bodhi tree), namely, the exclusive teaching of Mahāyāna that is for bodhisattva only. This is because, only the bodhisattvas with higher faculties can immediately grasp truth without having to go through preparatory stages. Although Śrāvakas are present, they are unable to comprehend this Sudden Teaching, and are isolated from it (Ta Ko-yü Hsiao). Since this teaching is not heard by Śrāvakas (Hsiao Pu-wen Ta) and does not have an effect on them, it remains Sudden (Ta Yi-hsiang Shih Tun).

The second period that is compared with “the sun that shines into deep valleys” (Tz ‘u-chao Yu-ku), is defined as “Gradual” (Chien), and is analogous with the flavor of cream. Being the opposite term of “Sudden,” “Gradual” refers to the teachings of the Buddha that carry the partial truths catering to either Śrāvakas or Mahāyānists, for the purpose of preparing listeners for the final disclosure of the Ultimate Truth. This includes the three stages of the teaching gradually ascending from the elementary to the profound doctrines. The three stages refer to this second period Āgama, the next third period Vaipulya, and the fourth period Prajn͂ā.

Due to the fact that Śrāvakas in the first period are unable to comprehend the profound truth, and are like the deaf and the dumb, the Buddha, in the second period, teaches them the doctrine of the Tripiṭaka, the Gradual Teaching (Chien-chiao) that is for Śrāvakas only. Although Mahāyānists are present, they are not recognized by Śrāvakas (Hsiao Ko-yü Ta, Ta Yin-yü Hsiao). Since the Buddha has not yet stated the non-distinction of Śrāvakayāna and Mahāyāna, Mahāyānists still differentiate themselves from Śrāvakas, and do not see the value of Śrāvakayāna (Ta Pu-yung Hsiao). As this teaching is exclusively Śrāvakayāna in nature, it remains gradual (Hsiao-i-hsiang Shih Chien).

The third period that is compared with “the sun that shines on level ground” (Tz’u-chao P’ing-ti), is also defined as “Gradual” (since the teaching of this period still contains the partial truth), and is analogous with the flavor of curdled milk. Nevertheless, the purpose of this period is to break through the teaching of Śrāvakayāna with the teaching of Mahāyāna (I-ta P’o-hsiao), in order to clarify the fact that the former teaching is only relative. Therefore, Chih-i calls it “Sudden and Gradual are equally presented” (Tun-chien Ping-ch ‘en).

The fourth period is compared with the time of day that is closest to noon, when the sunlight is getting stronger. This is the time when “adults are benefited by the light, and infants [who are seven days old] lose their eyesight [if they look at the sun]. Also, this period is defined as “Gradual” (since the Buddha did not yet announce the Ultimate Truth about liberation for all living beings), and is analogous with the flavor of butter. The significance of this period is to emphasize non-distinction between the teachings of Mahāyāna and Śrāvakayāna. Chih-i terms it “elucidating the teaching of Mahāyāna but encompassing the teaching of Śrāvakayāna” (Taihsiao Ming-ta), viz., Sudden and Gradual are not contradictory, but are complimentary to each other (Tun-chien Hsiang-tzu).

The fifth period is compared with the time of noon when “the sun shines equally on all levels of terrain.” This period is defined as “Gradual and Perfect” (Chien-yüan), and is analogous with the flavor of ghee. Perfect refers to the teaching of the Buddha that conveys the Ultimate Truth of the one Buddha-vehicle. Since this period is to integrate Śrāvakayāna with Mahāyāna (Hui-hsiao Kui-ta) (i.e., the Gradual Teaching is converged into the Perfect Teaching), it is thus called “Gradual and Perfect”. As a result of this convergence, there is not only no distinction between the Sudden and the Gradual, but both have been vanished and unified (Tun-chien Min-ho) when the real intention of the Buddha is displayed. That is, both Sudden and Gradual are instrumental in leading living beings to attain final Buddhahood.

The Profound Meaning of the Lotus Sutra: Tien-tai Philosophy of Buddhism