This is a followup to yesterday’s post about The Lotus Sutra: A Biography with a few additional ideas I want to save for later retrieval.

On the fate of the 5,000 arrogant monks who walked out in Chapter 2, Expedients, of the Lotus Sūtra:

For Zhiyi, and for many readers over the centuries, the Lotus Sūtra has two major messages. The first, found in the first half of the sūtra, is that there are not three vehicles; there is one vehicle, which will eventually transport all sentient beings to buddhahood. The second, found in the second half of the sūtra, is that the lifespan of the Buddha is immeasurable. These two doctrines are generally compatible with the Nirvāṇa Sūtra, allowing Zhiyi to continue to uphold the supremacy of the Lotus. But if everything is said in the Lotus, what is the purpose of the Nirvāṇa? Here, those five thousand haughty monks and nuns who walked out in the second chapter of the Lotus Sūtra come to the rescue. The sūtra does not explain what became of them, but Zhiyi explains that they returned to the assembly that surrounded the Buddha’s deathbed. The Buddha thus compassionately reiterated the central message of the Lotus Sūtra to those who had missed it the first time. It was also important, at the moment of his apparent passage into Nirvāṇa, for the Buddha to reiterate what he had declared in the Lotus: that like the wise physician, the Buddha only pretends to die; in fact his lifespan is immeasurable. (Page 56-57)

On the great merit earned by the grasshopper.

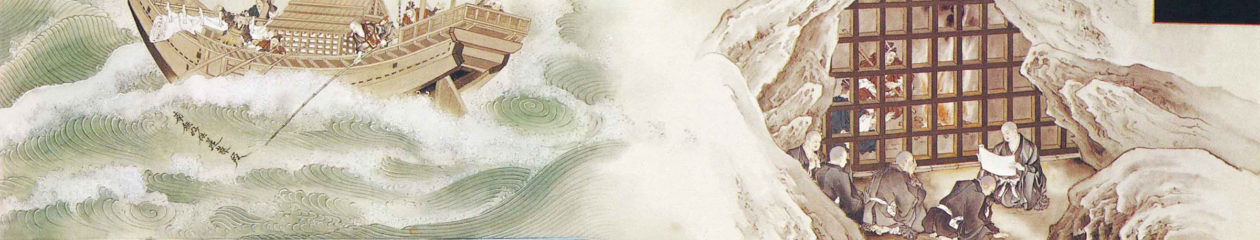

Discussing Great Japanese Miraculous Tales of the Lotus Sūtra (Dainihonkoku hokekyōkenki), completed in 1044 by the monk Chingen:

One of several anthologies of miracle tales about the Lotus, this collection includes rather standard Buddhist stories of miracle cures (a blind woman regains her sight by reciting the Lotus), divine retribution (a man who ridicules a reciter of the Lotus loses his voice), and deaths attended by heavenly fragrances, beautiful music, and auspicious dreams. In one story, a monk memorizes the first twenty-five chapters of the Lotus but, despite repeated efforts, is unable to memorize the final three. He eventually learns in a dream that in a previous life he had been a grasshopper who perched in a temple room where a monk was reciting the sūtra. After reciting the first seven scrolls of the sūtra (which contain the first twenty-five chapters), the monk rested before beginning the final roll. He leaned against the wall and inadvertently killed the grasshopper. The grasshopper was reborn as a human as a result of the merit he received from hearing the first twenty-five chapters of the Lotus. When he became a monk, however, he was unable to memorize the final three chapters because he, as the grasshopper, had died before he heard them. (Page 79-80)

On how Nichiren judged the six Buddhist schools of Nara.

He seems to have arrived at this conviction [of the supremacy of the Lotus Sūtra] through something of a process of elimination, but only after a serious survey of the Japanese sects of the day. He began with the belief that the word of the Buddha was superior to that of the various Indian Buddhist masters, such that one’s allegiance should be to a sūtra rather than to a treatise (śāstra). This immediately eliminated five of the six “Nara schools” of Buddhism, which were based on various Madhyamaka (Sanron), Yogācāra (Hossō), and Abhidharma treatises (Kusha and Jōjitsu), as well as on (in the case of Ritsu) the monastic code (vinaya). Among the Nara schools, that left only Kegon, based on the Flower Garland Sūtra, which Nichiren rejected. He already had an antipathy for Pure Land, but he was attracted to Shingon, famous for its doctrine that it is possible to “achieve buddhahood in this very body” (sokushin jōbutsu), that is, during the present lifetime. He found what would prove to be for him a more compelling doctrine in the Tendai sect, which, based in part on Zhiyi’s famous doctrine of “the three thousand realms in a single thought,” proclaimed that all beings are endowed with original enlightenment (hongaku). Nichiren eventually decided that the Tendai sect, with its conviction that the Lotus Sūtra was the Buddha’s highest teaching, was the superior form of Buddhism, although he felt that in the centuries since its founding, its purity had been diluted by the admixture of other practices, especially devotion to Amitābha. (Page 82-83)

On the topic of Nichiren Shoshu.

“We recall that in Nichiren Shōshū, the dharma in the three jewels is not the Lotus Sūtra; it is the three great secret doctrines: the honzon, the daimoku, and the kaidan.” (Page 221)

On SGI as a separate Buddhist organization

We find in the charter no mention of slandering the dharma (or the consequences of doing so), no mention of shakubuku, and no mention of the Lotus Sūtra. (Page 211)