A better time, and Nichiren’s thought about sin

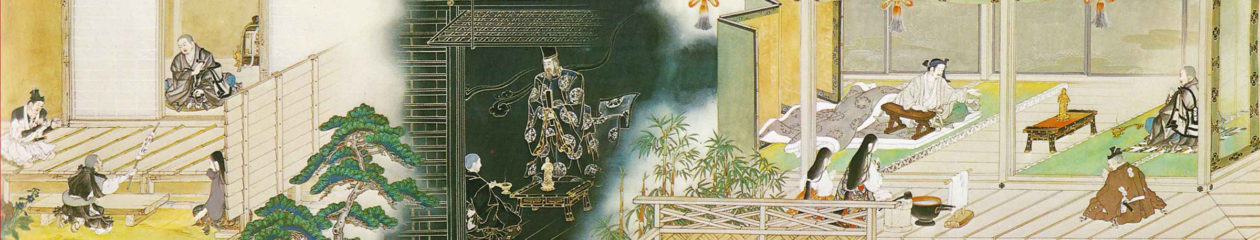

When Nichiren had finished the “Opening the Eyes,” amidst the snows of winter, with the coming of the spring a better time began for him. The governor of the island was much attracted by Nichiren’s saintly life, as well as by his strong personality. The government issued an order to protect the exile; Nichiren was given an abode at Ichi-no-sawa, a place on the slope of a range of hills. The local chief of this region admired and protected him, showing him great respect; his wife and son were converted. The place of exile became a veritable center of propaganda, and many flocked to listen to the sermons of the wonderful man. Nichiren reviewed his past experience anew, in calm reflection; the hardships he had gone through appeared in another light, and he now recognized that they were all in expiation of the grave sins accumulated from eternity through neglect or abandonment of duty, or through not having always lived as the true Buddhist. The strenuous repression of which he made so much in his combative propaganda meant the repression not only of others’ illusions and vices, but of his own. In a letter written about one month after the “Opening the Eyes,” he sums up the arguments expounded in that work, and speaks of himself as follows:

“That Nichiren suffers so much is not without remote causes. As is explained in the chapter on the Bodhisattva Sadāparibhūta, all abuses and persecutions heaped upon the Bodhisattva were the results of his previous karma. How much more, then, should this be the case with Nichiren, a man born in the family of an outcast fisherman, so lowly and degraded and poor! Although in his soul he cherishes something of the faith in the Lotus of Truth, the body is nothing but a common human body, sharing beastlike life, nothing but a combination of the two fluids, pink and white, the products of flesh and fish. Therein the soul finds its abode, something like the moon reflected in a muddy pool, like gold wrapped up in a dirty bag. Since the soul cherishes faith in the Lotus of Truth, there is no fear even before (the highest deities, such as) Brahmā and Indra; yet the body is an animal body. Not without reason others show contempt this man, because there is a great contrast between the soul and the body. And even this soul is full of stains, being the pure moonlight only in contrast to the muddy water; gold, in contrast to the dirty bag.

“Who, indeed, fully knows the sins accumulated in his previous lives? … The accumulated karma is unfathomable. Is it not by forging and refining that the rough iron bar is tempered into a sharp sword? Are not rebukes and persecutions really the process of refining and tempering? I am now in exile, without any assignable fault; yet this may mean the process of refining, in this life, the accumulated sins (of former lives), and being thus delivered from the three woeful resorts. …

“The world is full of men who degrade the Lotus of Truth, and such rule this country now. But have I, Nichiren, not also been one of them? Is that not due to the sins accumulated by deserting the Truth? Now, when the intoxication is over, I stand here something like a drunken man who having, while intoxicated, struck his parents, after coming to himself, repents of the offence. The sin is hardly to be expiated at once. … Had not the rulers and the people persecuted me, how could I have expiated the sins accumulated by degrading the Truth?”

Such reflections on his own sinfulness naturally led Nichiren to apply the same principles to his followers. No one is totally destitute of Buddha-nature, which is dormant in the innermost recess of the soul; but none is free from the sin of having disregarded and disobeyed the Truth. Nichiren is now fulfilling the oaths taken before Buddha, and thereby expiating his sins through a severe discipline in hardships. Persecutions are necessary accompaniments of the lives of those who labor for the sake of the Truth, because of their efforts to stir up the malicious and perverse nature of their fellow-beings, among whom the work of propagating the Truth is done. But the perils are at the same time a means of expiating the workers’ own grave sins. Moreover, an existence of any kind is never an individual matter, but always the result of a common karma, shared by all born in the same realm of existence. Hence the expiation made by any one individual is, in fact, made for the sake of all his fellow-beings. Both the persecutors and the persecuted share the common karma accumulated in the past, and therefore share also in the future destiny, the attainment of Buddhahood. Nichiren’s repression of others’ malice and vice is at the same time his own expiation and self-subjugation. How, then, should his followers not share his merit in extinguishing the accumulated sins, and preparing for the realization of the primeval Buddha-nature? “Therefore,” Nichiren exhorts his disciples, “believe in me, and emulate my spirit and work, in the firm faith that the Master is the savior and leader! Work together, united in the same faith! Then, the expiation of sins will be achieved for ourselves and for all our fellow-beings, because we all share in the common karma.”

The Exile In Sado And The Ripening of Nichiren's Faith in His Mission

A calm reflection and the attainment of faith in his mission 6o

His life in solitary exile 63

"The Heritage of the Great Thing Concerning Life and Death" 65

"Opening the Eyes "; the ethical aspects of religious life and faith 68

Absolute trust in Buddha's prophetic assurance 70

A better time, and Nichiren's thought about sin 73

NICHIREN: THE BUDDHIST PROPHET