His ideas about illness and death

The prophet had nearly reached the sixty-first year of his age, and for some time his health had been impaired. “Since I retired to this place, I have never been out of these mountains. During these eight years, illness and age have brought me severe suffering, and both body and mind seem to be crumbling into ruin. Especially since last spring, my illness has progressed, and from autumn to winter my weakness has increased day by day. During these ten days, I have taken no food, and my suffering is aggravated by the severe cold in the midst of a huge snowfall. My body is like a piece of stone, and my chest is as cold as ice.” The words are from a letter to a lady who had sent him rice and rice-beer, thanking her for the comfort her drink had brought him. Even a strong man of almost superhuman will, like Nichiren, was unable to resist the disease, which was doubtless the result of constant strife and suffering through thirty years of his life. His mind was perhaps preoccupied by his illness, and we have only eleven letters from the ten months preceding his death; yet some of these letters are still in a vigorous strain, and he dwells much on the ideals of his mission, in contrast to the actual condition of the country. He was a prophet to the last moment.

A letter that he wrote to Lord Toki is interesting as embodying Nichiren’s thoughts on disease. Toki had written to the Master about a plague that was raging in the country, and, it seems, had asked his opinion. In reply, Nichiren explained that there were two causes of the plague, one bodily and the other mental, which were reciprocally related, and produced by the malicious devils, who seize every opportunity of attack. The devils are, however, Nichiren says, nothing but the radical vices existing in each one of us from eternity; because both goods and ills are, according to T’ien T’ai’s conception of existence, inherent in our own nature. Not only diseases, but all evils are only manifestations of the radical and innate vices, and there will be no cure until these vices have been extirpated. Then the question is, Why are the faithful believers of the Lotus of Truth attacked by ills or devils? For the solution of this problem Nichiren has recourse to the doctrine of “mutual participation” [Ichinen Sanzen]. Just as the bliss of enlightenment in a particular individual is imperfect unless this bliss is shared by all fellow beings, so ills may attack even the holders of the Truth, even the messenger of the Tathāgata, so long as there exists any vice in the world in any of his fellow beings. And the believers of the Lotus are perhaps more frequently attacked by ills because the devils, regarding the true Buddhists as their most formidable adversaries, aim particularly at their lives.

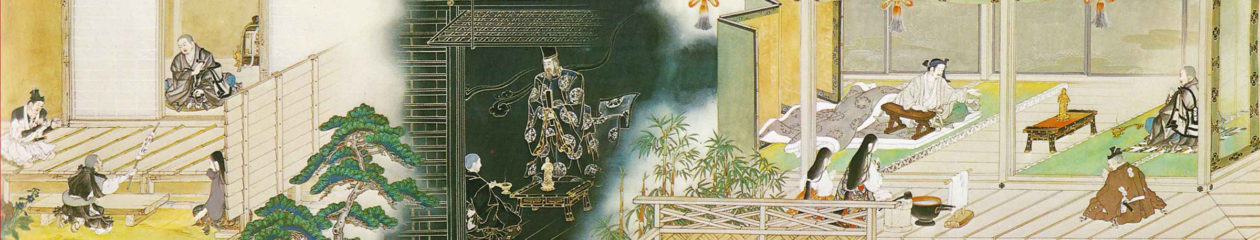

Such was Nichiren’s thought on illness in general. Applied to his own person, it was associated with his mission to establish the Holy See [Kaidan]. So long as the true Buddhism was taught only in theory, as was done by T’ien T’ai and Dengyō, the onset of the devils was not so violent as when the theory was translated into practice, as it was by Nichiren. This was the reason why he encountered so many perils as a result of his aggressive propaganda; they were to be explained in the same way as the illnesses which attacked him and his followers. In other words, the radical vices, and consequent ills, were aroused to rage by Nichiren’s propaganda, especially by his preparations for the establishment of the Holy See [Kaidan]. When this latter end should be completely achieved, there would be no more room for the vices to have their evil way. Seeing this, the devils run riot, for the purpose of staying the progress of the cause. Thus, Nichiren saw in the raging plague, and also in his own illness, a sign of the approaching fulfilment of his aim. “Does not the growing stubbornness of the resistance show the strength of the subjugating power? Why, then, should not the true Buddhist suffer, not only from illness but from perils of all sorts? Is not Nichiren’s life itself a living testimony to this truth?” Thus, he wrote in a letter dated the twenty-sixth day of the sixth month, 1282, which he meant to be his own sermon on illness and death, corresponding to Buddha’s sermon in the Book of the Great Decease [Nirvāṇa Sutra], “Our Lord Buddha revealed the Lotus of Truth on Vulture Peak, during eight years, in the last phase of his earthly life; then he left the Peak, and went northeastward to Kuśināgara, where he delivered the last sermon on the Great Decease, and manifested death.” This tradition occupied the mind of Nichiren, who had lived a life of sixty years in thorough-going conformity to, or emulation of, Buddha’s deeds and work.

The Last Stage of Nichiren’s Life and His Death

His ideas about illness and death 131

His last moments and his legacy 133

NICHIREN: THE BUDDHIST PROPHET