Buddhism for Today, p75In the [Chapter 4], we were taught that we must not have the servile idea that we have the capacity to understand the Buddha’s teachings only to a certain limited extent. We should abandon such trifling discriminations and devote ourselves to hearing and receiving the Law. The Parable of the Herbs states that every effort of ours will be surely rewarded. That is, though various kinds of plants and trees are produced in the same soil and moistened by the same rain, each develops according to its own nature. In the same way, though the Buddha’s teachings are only one, they are understood differently according to each hearer’s nature, intellect, environment, and so on.

Even if we have only a shallow understanding of the Buddha’s teachings or can practice only a part of them, this is never useless. Every effort will be surely rewarded with the merits of the Law. But we should not be satisfied with this reward. We must always desire and endeavor to deepen our understanding and to elevate ourselves further. Thus, we can use shallow faith and discernment as the first step in advancing ourselves to a higher level of faith and discernment. Ascending step by step, we can unfailingly reach a superior state of mind. We should understand this well when we read the latter part of this chapter. It is stated here that though the Buddha’s teachings are one, there are differences in faith and discernment according to one’s capacity to understand the teachings. But we must not interpret this as stating an absolute condition.

Category Archives: d8b

Combining Faith and Discernment

Buddhism for Today, p64The mental state generated by the firsthand encounter with mystery is called faith. A religion whose teachings a person tries to explain entirely by reason has no power to move others because this person has only a theoretical understanding and cannot put his theory into practice. Such a religion does not produce the energy to cause others to follow it. True faith has power and energy. However uneducated a person may be and however humble his circumstances, he can save others and help them promote his religion if he only has faith. But if he has faith in what is fundamentally wrong, his energy exerts a harmful influence on society and those around him. Therefore faith and discernment must go together. A religion cannot be said to be true unless it combines faith and discernment. The Buddha’s teachings can be understood by reason. They do not demand blind, unreasoning faith. We must understand the Buddha’s teachings by listening to preaching and by reading the sutras. As we advance in our discernment of these teachings, faith is generated spontaneously.

When a person who has a flexible mind is not advanced in discernment, he develops faith as soon as he is told, “This is a true teaching.” So far as the teaching of the Lotus Sutra is concerned, that is all right, because he will gradually advance in discernment through hearing and reading its teaching.

In short, we can enter a religion from the aspect either of faith or of discernment, but unless a religion combines both aspects, it does not have true power.

The Status of Arhatship

Two Buddhas, p58-59Different Mahāyāna sūtras treat the status of Arhatship — the goal of the mainstream tradition — in different ways, for example, as a lesser but still viable goal (as in The Inquiry of Ugra) or as an outright misunderstanding on the part of the Buddha’s disciples (as in the Vimalakirti Sūtra). There was a shared consensus, however, that persons of the first two vehicles, in liberating themselves from rebirth by achieving the goal of nirvāṇa, were thereby excluded from achieving the buddhahood that is gained on the bodhisattva path. The Lotus Sūtra is distinct in asserting that the apparent threefold division of the teaching into the distinct vehicles of śrāvakas, pratyekabuddhas, and bodhisattvas is only apparent: ultimately, all are following the bodhisattva path and will eventually become buddhas. This “revival” of śrāvakas, causing them to realize that they are actually bodhisattvas, was identified early on by Chinese exegetes as a crucial feature of the Lotus.

A Seed that Flowers and Bears Fruit in the Very Moment of Its Acceptance

Two Buddhas, p119-120The concept of sowing, maturing, and harvesting suggests a linear process developing over time. Mahāyāna thought traditionally maintained that fulfilling the bodhisattva path requires three incalculable eons. However, as we have seen, Nichiren drew on both Tendai and esoteric notions of realizing buddhahood “with this body” to argue that buddhahood is accessed in the very act of chanting Namu Myōhō-renge-kyō. The daimoku, in other words, is a “seed” that flowers and bears fruit in the very moment of its acceptance. This goes to the heart of how Nichiren understood the Final Dharma age. In the age of the True Dharma and the age of the Semblance Dharma, people practiced according to a linear model, gradually eradicating delusions and accumulating merit, eventually culminating in the attainment of buddhahood after countless lifetimes of practice. But in chanting the daimoku of the Lotus Sūtra, the practice for the mappō era, practice and enlightenment, sowing and harvest, occur simultaneously, and buddhahood is realized in this very body. In other words, in the Final Dharma age, the direct realization of buddhahood becomes accessible to ordinary people. Nichiren’s claim paradoxically inverts the negative soteriological implications of the benighted mappō era and makes it the ideal time to be alive. “Rather than be great monarchs during the two thousand years of the True Dharma and Semblance Dharma ages, those concerned for their salvation should rather be common people now in the Final Dharma age,” he wrote. “It is better to be a leper who chants Namu Myōhō-renge-kyō than to be chief abbot of the Tendai school,” the highest position in the religious world of Japan at the time.

The Revelation of the Universal Ground

Two Buddhas, p127-128According to Zhiyi’s parsing, Chapters Two through Nine of the Lotus Sūtra comprise the main exposition of the “trace teaching,” or shakumon, the first fourteen chapters of the Lotus Sūtra. These chapters assert that followers of the two “Hinayāna” vehicles can achieve buddhahood. For the sūtra’s compilers, this message subsumed the entire Buddhist mainstream within its own teaching of the one buddha vehicle and extended the promise of buddhahood to a category of persons — śrāvakas and pratyekabuddhas — who had been excluded from that possibility in other Mahāyāna sūtras. In Nichiren’s day, however, the idea of the one vehicle, that buddhahood is in principle open to all, represented the mainstream interpretive position, and his own reading therefore has a somewhat different emphasis. For Nichiren, the sūtra’s assertion that even persons of the two vehicles can become buddhas pointed to the mutual possession of the ten realms and the three thousand realms in a single thought-moment, without which any talk of buddhahood for anyone, even those following the bodhisattva path, can be no more than an abstraction. The revelation of this universal ground, he said, especially in the “Skillful Means” chapter, constitutes the heart of the shakumon portion of the Lotus. Nonetheless, he regarded Chapter Two through Chapter Nine, the main exposition section, as having been preached primarily for the benefit of persons during the Buddha’s lifetime. The remaining chapters, Chapter Ten through Chapter Fourteen, which constituted the remainder of the trace teaching, he saw as explicitly directed toward those who embrace the Lotus after the Buddha’s passing, and therefore, as having great relevance for himself and his followers.

The Initial Chapters of Lotus Sūtra Open Buddhahood to All Beings

Two Buddhas, p96Unlike Saichō, … Nichiren did not ground his own argument that all can attain buddhahood in claims for universal suchness, a term that occurs only rarely in his writings but, rather, in the mutual inclusion of the ten realms. This doctrine also renders irrelevant Hossō and Kegon claims that the Lotus Sūtra should be ranked below the Explanation of the Intention or Flower Garland sūtras because the parable of the wealthy man and his impoverished son, on which the Tendai hierarchy of Buddhist teachings is based, was spoken by śrāvakas. Nichiren wrote, “The four śrāvakas expressed their understanding, saying, ‘The most magnificent jewels have been obtained without being sought or awaited.’ They represent the śrāvaka realm within ourselves.” Central to Nichiren’s understanding was the idea that, because the ten realms are mutually inclusive, if beings of one realm can attain buddhahood, so can those of any other. In his reading, the initial chapters of the Lotus Sūtra open buddhahood not merely to previously exduded śrāvakas, but to all beings.

The Rich Man, the Poor Son and the Five Periods

Two Buddhas, p91-93[A]fter Zhiyi’s time, through the efforts especially of Zhanran and the Korean scholar-monk Chegwan, the Tiantai school gradually developed a model that divides the Buddha’s teaching career into five periods that span fifty years. According to this model, the Buddha began by preaching the Flower Garland Sūtra (Avatamsaka Sūtra), a highly advanced doctrine directed solely to bodhisattvas. None of the śrāvakas in the assembly could understand it and were struck dumb, just as the impoverished son was terrified when first forcibly approached by his father’s attendants. Seeing that the Flower Garland teaching was beyond his auditors’ capacity, the Buddha then backtracked and for twenty years preached the āgamas, … emphasizing the four noble truths, the twelve-linked chain of dependent origination, and the goal of nirvāṇa — that is, the teachings sometimes disparaged as the “Hinayāna.” This period corresponds to the wealthy man hiring his son to sweep manure for twenty years. In the third period, seeing that his followers were maturing, the Buddha preached the vaipulya or introductory Mahāyāna teachings such as the Vimalakirti Sūtra, which criticize the one-sided emphasis on emptiness and detachment found in the āgamas and instead extol the way of the bodhisattva. This corresponds to the son having “free access to his father’s house” yet still living in his own humble quarters. In the fourth period, the Buddha preached the prajn͂ā or wisdom teachings, which integrate all of his teachings up to that point in the two discernments of emptiness and wisdom by which bodhisattvas both uproot attachment and act compassionately in the world. This corresponds to the wealthy man entrusting the care of his fortune to his impoverished son. Then finally, in the fifth period, during the last eight years of his life, the Buddha set aside the coarse and incomplete provisional teachings of the preceding four periods and preached the perfect teaching that opens buddhahood to all. This teaching is represented by the Lotus Sūtra, and — in the Tiantai reading — restated in the Nirvāṇa Sūtra, said to have been preached just before the Buddha’s passing. This corresponds to the father, now approaching death, publicly acknowledging his son and bequeathing all of his wealth to him. In this way, the parable of the wealthy householder provided a basis for grasping the entirety of the Buddha’s teachings as integrated into a single, comprehensive chronological and soteriological agenda, by which he sought to gradually cultivate his followers’ capacity until they were mature enough to receive and accept the message of the one buddha vehicle.

Our Spiritual Parent

We can compare the Buddha’s method with that of parents who raise their children with tender loving care. Most of the time, the children are not aware of how much is being done for them. They take their parents’ love for granted. Often they fully appreciate all that their parents have done for them only after the parents have died. Then they wish they had displayed more gratitude when they had the chance. The parents, on the other hand, must be careful, and not give their children everything they ask for. Pampered children can quickly become spoiled and helpless. Their parents will not be able to care for them forever.

Introduction to the Lotus SutraDeparting from the Passivity of the Lesser Vehicle

The narrative … told by the four sravakas is called the “Parable of the Rich Man and His Poor Son.” As we can see from what they have said, the Lesser Vehicle which they had been following stressed escape from this world of sorrows into a pure world of contemplation. Its concept of enlightenment was also passive. It concluded that “nothing is different from anything else,” and “there is nothing more to seek.” This view rejected the reality of this world and the necessity of working to change it. The Great Vehicle, on the other hand, interpreted the same doctrine [that nothing is substantial] positively as becoming a buddha in this world and transforming it into a buddha-world. Enlightenment is to be achieved within the turmoil of our daily life, not in silent seclusion. The four “hearers” now realize that they, too, have obtained the wonderful law of the Great Vehicle and have departed from the passivity of the Lesser Vehicle.

Introduction to the Lotus SutraA Father and His Children

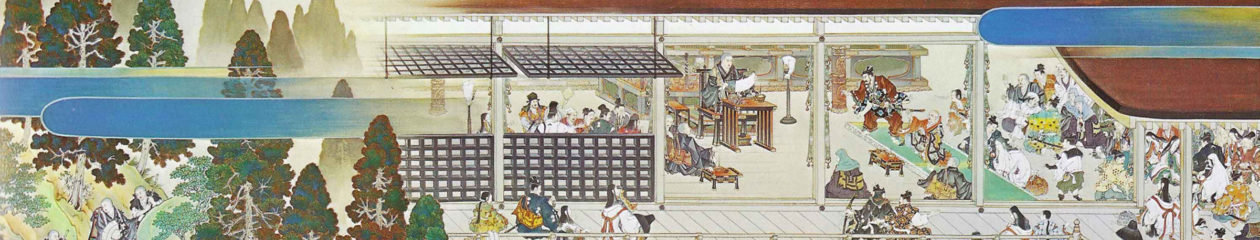

The Lotus Sutra contains seven parables, three of which are best known. The first is the “Parable of the Burning House of the Triple World” in Chapter Three. The second is the “Parable of the Rich Man and His Poor Son” in Chapter Four. The “Parable of the Physician and His Children” is presented in Chapter Sixteen. These three parables allegorically show the relationship between the Buddha and living beings by presenting a parental relationship. That is, faith in the Buddha is similar to the faith of a child in his father; and the Buddha’s compassion toward living beings is like a father’s love for his children. In other words, natural feelings drawn from the norms of everyday life eventually lead us toward faith in the Buddha.

Introduction to the Lotus Sutra