Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p175-176Now the Lotus Sutra describes Avalokiteśvara’s marvelous power to redeem:

Even if someone whose thoughts are malicious

Should push one into a great pit of fire,

By virtue of the constant mindfulness of Sound-Observer

The pit of fire would turn into a pool.How can we understand this verse? Even if we are pushed into a pit of fire, when we know how to be mindful, how to practice the recollection of the powerful energy of Avalokiteśvara, the fire will be transformed into a cool lotus pond.

The word “fire” in this verse represents anger. Not only individuals are subject to the afflictions of anger and fear – they also occur on the levels of communities, societies, and nations. Sometimes an entire country can be plunged into a pit of fire. The September 11 attacks in New York and Washington, D.C., triggered a huge sea of anger, despair, and fear, and the whole United States was in danger of plunging into that pit of fire. Many Americans were looking at their televisions, listening to the inflammatory rhetoric of the politicians, and desiring revenge and retaliation. They were not able to stop and cultivate the mindfulness to look deeply into the situation in the weeks and months after the devastating event.

Yet not all Americans participated in this upwelling of anger, fear, and despair. I was in New York at the time, with friends, and we shared the insight that we cannot respond effectively to anger with anger. Violence should not be used to counter violence; we must practice looking deeply to see the situation clearly and act with wisdom and compassion. Many people contacted me in the days immediately after the attacks, people who were practicing in order to help the nation remain calm. An angry, violent reaction could trigger a war. I began a fast, and invited friends in Europe, America, and elsewhere to join me in the fast in order to practice calming and looking deeply. I contacted congresspeople, politicians, and others, including Ambassador Andrew Young (who sat with me during interviews), who shared the view that we should not attack out of anger. Over 2,000 people attended the talk I gave at the Riverside Church soon after the attacks, and over a thousand were turned away for lack of space.

Some politicians publicly expressed the desire to support this view, but in the political climate of retaliation, they felt unable to do so. And there were many others who shared this view but did not have enough courage to speak out. The wisdom was there, the compassion was there, but the environment was not favorable for the expression of that wisdom and compassion. Yet not all Americans shared the viewpoint of the president or supported the government’s retaliatory action. We must always remember, especially in times of great turmoil or suppression, that we have more friends with us than we may think.

The message of Buddhism is very clear – all violence is injustice. Escalation of anger and violence leads only to more anger and violence, and in the end to total destruction. Violence and hatred can only be neutralized by compassion and loving kindness. When you find yourself in a difficult situation, when you are about to fall into a pit of fire, if you know how to practice mindfulness of compassion and invoke the embodiment of compassion, Avalokiteśvara, then you will be able to stop, calm yourself, and look more deeply and clearly into your situation. Anger and the desire for retaliation and revenge will subside and you will be able to find the better way to respond. Understanding that we inter-are, and that any violence done to another is ultimately violence done to ourselves, we practice mindfulness of compassion so as not to cause more suffering to ourselves, our own people, or those on the so-called other side.

The ocean of fire, the pit of suffering, fear, and anger is a reality. The suffering and despair of the world is enormous, and the desire to punish those who harm us, to retaliate out of our fear and anger, is very strong in us. All of this causes the pit of fire to grow larger and it threatens to consume us all. We can turn the ocean of fire into a cool lake by practicing mindfulness of love and invoking the messenger of love, Avalokiteśvara. As the Lotus Sutra tells us, the bodhisattva of compassion has many aspects and can manifest in many forms and with many names. This bodhisattva is the universal gateway to the path of compassion and reconciliation, and through mindfulness of love, understanding, and compassion the ocean of fire is transformed into a cool, refreshing lotus pond.

Category Archives: d29b

Enjoying the Journey

Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p153-154In the opening scene of [Chapter 23], one of the bodhisattvas from another part of the cosmos, Beflowered by the King of Constellations, asks the Buddha, “World-Honored One, how does the bodhisattva Medicine King travel in the saha world?” In the Chinese Vietnamese version of the Sutra, this passage reads “What is his business in the saha world?” But it is not really a matter of doing business; a better understanding of this passage would be, “How is that bodhisattva enjoying his journey in the world?” In the chapter on Avalokiteshvara in the Vietnamese version of the Lotus Sutra we see the phrases “enjoying a trip” and “enjoying a stay.” So the great bodhisattvas are those who know how to be at ease and enjoy their travels in the saha world.

We have to learn how to enjoy ourselves as we journey through this saha world. When we understand this, we will be more at ease and not think of our life as being some kind of task that we must accomplish. We do not have to scheme or hurry. We will be able to offer our service and work because we enjoy it. We can work without attachment to outcome. We can perform all our actions – organizing a retreat, building a Sangha, working with prisoners – in a spirit of freedom, liberation, and joy, rather than being bound up by notions of achieving a certain level of success or attainment.

The Action of the Bodhisattvas

Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p143Practicing the path and liberating beings from suffering is the action of the bodhisattvas. The Lotus Sutra introduces us to a number of great bodhisattvas, such as Sadaparibhuta (Never Disparaging), Bhaisajyaraja (Medicine King), Gadgadasvara (Wonderful Sound), Avalokiteshvara (Hearer of the Sounds of the World), and Samantabhadra (Universally Worthy). The action taken up by these bodhisattvas is to help living beings in the historical dimension recognize that they are manifestations from the ground of the ultimate. Without this kind of revelation we cannot see our true nature. Following the bodhisattva path, we recognize the ground of our being, our essential nature, in the ultimate dimension of no birth and no death. This is the realm of nirvana – complete liberation, freedom, peace, and joy.

The Dimension of Action

Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p142-143One of the most important and influential schools of Chinese Buddhism, the Tiantai school, divides the Lotus Sutra into two parts: the first fourteen chapters representing the historical dimension and the last fourteen chapters representing the ultimate dimension. But this method has some shortcomings. There are elements of the ultimate dimension in the first fourteen chapters and elements of the historical in the second. There is also a third very important dimension, the dimension of action.

These dimensions cannot be separated; they inter-are. Here is an example. When we look at a bell we can see that it is made of metal. The manifestation of the bell carries the substance of metal within. So within the historical dimension – the form of the bell – we can see its ultimate dimension, the ground from which it manifests. When the bell is struck, it creates a pleasant sound. The pleasant sound created by the bell is its function. The purpose of a bell is to offer sound in order for us to practice. That is its action. Function is the dimension of action, the third dimension along with, and inseparable from, the historical and ultimate dimensions.

We need to establish a third dimension of the Lotus Sutra to reveal its function, its action. How can we help people of the historical dimension get in touch with their ultimate nature so that they can live joyfully in peace and freedom? How can we help those who suffer open the door of the ultimate dimension so that the suffering brought about by fear, despair, and anxiety can be alleviated? I have gathered all the chapters on the great bodhisattvas into this third action dimension, the bodhisattva’s sphere of engaged practice.

A Goddess of Mercy

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p274The list of misfortunes from which one can be saved by calling upon Kwan-yin is interesting but not terribly important, as the meaning is quite clear – Kwan-yin can save anyone from any misfortune. The list simply provides concrete examples. This power to save is why early Jesuit missionaries to China invented the term Goddess of Mercy to refer to Kwan-yin and relate her to Mary, the mother of Jesus. Kwan-yin, in fact, has been and still is a goddess of mercy for a great many, answering their prayers and bringing them comfort.

Of course, those who would follow the bodhisattva way should see great bodhisattvas as models for us and not be looking to gods or goddesses for special favors.

The Kind of Wisdom Embodied in Kwan-yin

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p276Compassion is a useful virtue, in that it can be effectively used by anyone. One of the most impressive things one can experience, as I have on many occasions, is the compassion that dying people often have for those around them. On many occasions I have seen dying people attempt to calm and cheer friends and relatives at their bedside. Of course, everyone can be wise to some degree as well, but there surely is a sense in which the way of compassionate action is more open to everyone than a way that emphasizes the acquisition of wisdom.

Compassion is best embodied in skill, in compassionate action. The tools in the hands of the Thousand-armed Kwan-yin symbolize the many means by which Kwan-yin can help living beings in need. This imagery is, I believe, revealing of the kind of wisdom embodied in Kwan-yin – not some kind of esoteric knowledge of the mind alone, but the practical wisdom found not only in minds but also in hands.

But skill is, after all, a kind of wisdom. So compassion should not be seen in contrast to wisdom but only in contrast to disembodied wisdom. To be compassionate is to embody compassion, not just to feel it or think about it or contemplate it. It is to actualize compassion in the world, wherever we are, and thus in our relationships with relatives, neighbors, friends, and even strangers. It is to be compassionate. This is to embody the Buddha, that is, to give life to the Buddha in the present world.

The Power of Practice

Vasubandhu's Commentary on the Lotus Sutra, p 148The power of practice is illustrated by five entrances: l) the power from teaching, 2) the power from the practice of undertaking hardships, 3) the power from protecting living beings from difficulties, 4) the power from the excellence of merits, and 5) the power from protecting the Dharma.

- The power from teaching has three entrances to the Dharma that are shown in the chapter “Supernatural Powers”: [the buddhas] extend their long, broad tongues in order to cause [those present] to remember; [they] coughed [before] speaking the verses in order to cause [those present to listen, and after having made them listen they caused them not to abandon the true practice; [they] snapped their fingers to enlighten living beings and to cause those who were practicing the path to attain enlightenment.

- The power from the practice of undertaking hardships is illustrated in the chapter “Bodhisattva Bhaiṣajyarāja” [Medicine King]. The chapter “Bodhisattva Gadgadasvara” [Wonderful Voice] also illustrates the power from the practice of undertaking hardships [in regard to] giving guidance to living beings.

- The power from protecting living beings from difficulties is shown in the chapter “Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara” and the chapter “Magical Spells.”

- The power from the excellence of merits is shown in the chapter “King Śubhavyūha.” The two boys have such power through the roots of good merit [they had planted] in past lives.

- The power from protecting the Dharma is shown in the chapter “Bodhisattva Samantabhadra” and in later chapters.

Accepting and Upholding the name of Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara

Vasubandhu's Commentary on the Lotus Sutra, p 148-149[I]t is said, “He who accepts and upholds the name of Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, and he who accepts and upholds the names of all the buddhas as numerous as the sands of sixty-two koṭis of Ganges Rivers, will each produce equal merit.” This has two meanings: 1) the power of faith and 2) complete knowledge.

The power of faith has two types: l) complete faith that one’s body is no different from the body of Avalokiteśvara, and 2) reverence felt toward Avalokiteśvara, so that one also believes one can completely attain such qualities as his.

Complete knowledge means the ability to be determined and to know the element of reality (dharmadhātu). “The element of reality” is referred to as the nature of reality (dharmatā). This “nature of reality” is referred to as the universal absolute body of all the buddhas and the bodhisattvas. “The universal body” is the true absolute body.

Bodhisattvas in the first stage are able to penetrate it. Therefore, one who accepts and upholds the names of all the buddhas as numerous as the sands of sixty-two koṭis of Ganges Rivers and one who accepts and upholds the name of Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara will both produce merit without any difference.

Compassion, Wisdom and Action

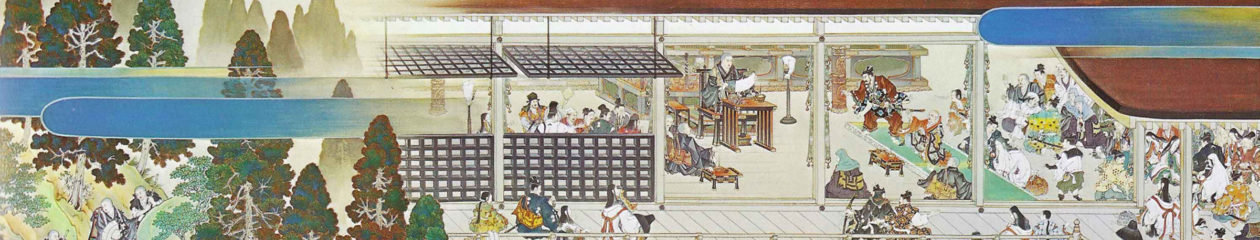

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p298-299In East Asian Buddhist temples and art one can find portrayals of many different bodhisattvas, but only five are found over and over again, in nearly all temples and museums. Their Indian names are Avalokiteshvara, Maitreya, Manjushri, Kshitigarbha, and Samantabhadra. In English they commonly called Kwan-yin (from Chinese), Maitreya, Manjushri (both from Sanskrit), Jizo (from Japanese), and Universal Sage. All except Jizo are prominent in the Lotus Sutra, though in different ways. While both Kwan-yin and Universal Sage have entire chapters devoted to them, except for a mention of Kwan-yin as present in the great assembly of Chapter 1, they do not otherwise appear in the rest of the text, while Manjushri and Maitreya appear often throughout the Sutra. In typical Chinese Buddhist temples, where the central figure is a buddha or buddhas, to the right one can see a statue of Manjushri mounted on a lion, and to the left Universal Sage riding on an elephant, usually a white elephant with six tusks.

While both Kwan-yin and Maitreya are said to symbolize compassion and Manjushri usually symbolizes wisdom, Universal Sage is often used to symbolize awakened action, embodying wisdom and compassion in everyday life. Above the main entrance to Rissho Kosei-kai’s Great Sacred Hall, for instance, there is a wonderful set of paintings depicting Manjushri and wisdom on the right, Maitreya and compassion on the left, and in the middle, the embodiment of these in life – Universal Sage Bodhisattva.

The Compassionate Action of Bodhisattvas

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p275-276Buddhism, perhaps especially Indian Buddhism, was closely associated with the goal of “supreme awakening,” and therefore with a kind of wisdom, especially a kind of wisdom in which doctrines and teachings are most important. Even the term for Buddhism in Chinese and Japanese means “Buddhist teaching.”

With the development of Kwan-yin devotion, while wisdom remained important, compassion came to play a larger role in the relative status of Buddhist virtues, especially among illiterate common people. Thus, there was a slight shift in the meaning of the “bodhisattva way.” From being primarily a way toward an enlightened mind, it became primarily the way of compassionate action to save others.

The Dharma Flower Sutra itself, I believe, can be used to support the primacy of either wisdom or compassion. When it is teaching in a straightforward way, the emphasis is on teaching the Dharma as the most effective way of helping or saving others. But, taken collectively, the parables of the Dharma Flower Sutra suggest a different emphasis. The father of the children in the burning house does not teach the children how to cope with fire; he gets them out of the house. The father of the long-lost, poor son does not so much teach him in ordinary ways as he does by example and, especially, by giving him encouragement. The guide who conjures up a fantastic city for weary travelers does not teach by giving them doctrines for coping with a difficult situation; instead, he gives them a place in which to rest, enabling them to go on. The doctor with the children who have taken poison tries to teach them to take some good medicine but fails and resorts instead to shocking them by announcing his own death. All of these actions require, of course, considerable intelligence or wisdom. But what is emphasized is that they are done by people moved by compassion to benefit others.