The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p216-217Over and over again in the Dharma Flower Sutra we are encouraged to “receive, embrace, read, recite, copy, teach, and practice” the Dharma Flower Sutra. Thus, the fact that Never Disrespectful Bodhisattva did not read or recite sutras is quite interesting. I think it is an expression of the general idea in the Dharma Flower Sutra that, while various practices are very important, what is even more important is how one lives one’s life in relation to others. The references to bodhisattvas who do not follow normal monastic practices, including reading and recitation of sutras, but still become fully awakened buddhas indicates that putting the Dharma into one’s daily life by respecting others, and in this way embodying the Dharma, is more important than formal practices such as reading and recitation.

Category Archives: d25b

Taking Personally the Three Phases of the Dharma

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p214We can, of course, understand the three phases [of the Dharma] not as an inevitable sequence of periods of time, but as existential phases of our own lives. There will be times when the Dharma can be said to be truly alive in us, times when our practice is more like putting on a show and has little depth, and times when the life of the Dharma in us is in serious decline. But there is no inevitable sequence here. There is no reason, for example, why a period of true Dharma cannot follow a period of merely formal Dharma. And there is no reason to assume that a period has to be completed once it has been entered. We might lapse into a period of decline, but with the proper influences and circumstances we could emerge from it into a more vital phase of true Dharma. A coming evil age is mentioned several times in the Dharma Flower Sutra, but while living in an evil age, or an evil period of our own lives, makes teaching the Dharma difficult, even extremely difficult, nowhere does the Dharma Flower Sutra suggest that it is impossible to teach or practice true Dharma.

The Teaching Given to Maitrayaniputra

Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p149-150Sadaparibhuta [Never-Despising Bodhisattva]represents the action of inclusiveness, kshanti. Kshanti, one of the six paramitas… . Kshanti is also translated as “patience,” and we can see this great quality in Sadaparibhuta and in one of the Shakyamuni’s disciples, Purna, who is praised by the Buddha in the eighth chapter of the Lotus Sutra. While the Lotus Sutra only mentions Purna in passing, he is the subject of another sutra, the Teaching Given to Maitrayaniputra. In this sutra, after the Buddha had instructed Purna in the practice, he asked him, “Where will you go to share the Dharma and form a Sangha?” The monk said that he wanted to return to his native region, to the island of Sunaparanta in the Eastern Sea.

The Buddha said, “Bhikshu, that is a very difficult place. People there are very rough and violent. Do you think you have the capacity to go there to teach and help?”

“Yes, I think so, my Lord,” replied Purna.

“What if they shout at you and insult you?”

Purna said, “If they only shout at me and insult me I think they are kind enough, because at least they aren’t throwing rocks or rotten vegetables at me. But even if they did, my Lord, I would still think that they are kind enough, because at least they are not using sticks to hit me.”

The Buddha continued, “And if they beat you with sticks?”

“I think they are still kind enough, since they are not using knives and swords to kill me.”

“And if they want to take your life? It’s possible that they would want to destroy you because you will be bringing a new kind of teaching, and they won’t understand at first and may be very suspicious and hostile,” the Buddha warned.

Purna replied, “Well, in that case I am ready to die. Because my dying will also be a kind of teaching and because I know that this body is not the only manifestation I have. I can manifest myself in many kinds of bodies. I don’t mind if they kill me, I don’t mind becoming the victim of their violence, because I believe that I can help them.”

The Buddha said, “Very good, my friend. I think that you are ready to go and help there.”

So Purna went to that land and he was able to gather a lay Sangha of 500 people practicing the mindfulness trainings and to establish a monastic community of around 500 practitioners. He was successful in his attempt to teach and transform the violent ways of the people in that country. Purna exemplifies the practice of kshanti, inclusiveness.

Following the Practice of Sadaparibhuta

Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p146This is the practice of this great bodhisattva – to regard others with a compassionate and wise gaze and hold up to them the insight of their ultimate nature, so that they can see themselves reflected there. Many people have the idea that they are not good at anything, they are not able to be as successful as other people. They cannot be happy; they envy the accomplishments and social standing of others while regarding themselves as failures if they do not have the same level of worldly success.

We have to try to help those who feel this way. Following the practice of Sadaparibhuta, we must come to them and say, “You should not have an inferiority complex. I see in you some very good seeds that can be developed and make you into a great being. If you look more deeply within and get in touch with those wholesome seeds in you, you will be able to overcome your feelings of unworthiness and manifest your true nature.”

The Action of the Bodhisattvas

Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p143Practicing the path and liberating beings from suffering is the action of the bodhisattvas. The Lotus Sutra introduces us to a number of great bodhisattvas, such as Sadaparibhuta (Never Disparaging), Bhaisajyaraja (Medicine King), Gadgadasvara (Wonderful Sound), Avalokiteshvara (Hearer of the Sounds of the World), and Samantabhadra (Universally Worthy). The action taken up by these bodhisattvas is to help living beings in the historical dimension recognize that they are manifestations from the ground of the ultimate. Without this kind of revelation we cannot see our true nature. Following the bodhisattva path, we recognize the ground of our being, our essential nature, in the ultimate dimension of no birth and no death. This is the realm of nirvana – complete liberation, freedom, peace, and joy.

The Practice of a Bodhisattva in the Action Dimension

Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p142-143In Chapter 20 of the Lotus Sutra, we are introduced to a beautiful bodhisattva called Sadaparibhuta, “Never Disparaging” or “Never Despising.” This bodhisattva never underestimates living beings or doubts their capacity for Buddhahood. His message is, “I know you possess Buddha nature, and you have the capacity to become a Buddha,” and this is exactly the message of the Lotus Sutra: you are already a Buddha in the ultimate dimension, and you can become a Buddha in the historical dimension. Buddha nature, the nature of enlightenment and love, is already within you; all you need do is get in touch with it and manifest it. Never Disparaging Bodhisattva is there to remind us of the essence of our true nature.

This bodhisattva removes the feelings of worthlessness and low self-esteem in people. “How can I become a Buddha? How can I attain enlightenment? There is nothing in me except suffering, and I don’t know how to get free of my own suffering, much less help others. I am worthless.” Many people have these kinds of feelings, and they suffer because of them. Never Disparaging Bodhisattva works to encourage and empower people who feel this way, to remind them that they too have Buddha nature, they too are a wonder of life, and they too can achieve what a Buddha achieves. This is a great message of hope and confidence. This is the practice of a bodhisattva in the action dimension.

The Dimension of Action

Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p142-143One of the most important and influential schools of Chinese Buddhism, the Tiantai school, divides the Lotus Sutra into two parts: the first fourteen chapters representing the historical dimension and the last fourteen chapters representing the ultimate dimension. But this method has some shortcomings. There are elements of the ultimate dimension in the first fourteen chapters and elements of the historical in the second. There is also a third very important dimension, the dimension of action.

These dimensions cannot be separated; they inter-are. Here is an example. When we look at a bell we can see that it is made of metal. The manifestation of the bell carries the substance of metal within. So within the historical dimension – the form of the bell – we can see its ultimate dimension, the ground from which it manifests. When the bell is struck, it creates a pleasant sound. The pleasant sound created by the bell is its function. The purpose of a bell is to offer sound in order for us to practice. That is its action. Function is the dimension of action, the third dimension along with, and inseparable from, the historical and ultimate dimensions.

We need to establish a third dimension of the Lotus Sutra to reveal its function, its action. How can we help people of the historical dimension get in touch with their ultimate nature so that they can live joyfully in peace and freedom? How can we help those who suffer open the door of the ultimate dimension so that the suffering brought about by fear, despair, and anxiety can be alleviated? I have gathered all the chapters on the great bodhisattvas into this third action dimension, the bodhisattva’s sphere of engaged practice.

Sharing in the Tathagata’s Limitless Lifespan and Great Spiritual Power

Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p127-128To complete our discussion of the ultimate dimension we skip ahead to Lotus Sutra Chapter 21, “The Supernatural Powers of the Thus Come One.” The supernatural power, or spiritual energy, of the Tathagata is his capacity to realize the practice. Naturally this spiritual power is based in the infinite life span of the Tathagata, the Buddha’s ultimate nature. We have already seen that the Tathagata cannot be placed in a frame of calculable space and time. The Tathagata is beyond our conception of the bounds of space and time. The Tathagata is not one but many; the Tathagata is not only here in this moment but everywhere at all times, in manifestation bodies as numerous as the sands of the Ganges. So, based on the foundation of his infinite life span and ultimate nature, we can see that the spiritual power of the Tathagata is very great, beyond our ability to imagine it.

The essential message of Chapter 21 is that our practice is to share in the Tathagata’s limitless lifespan and great spiritual power. Just as when we look deeply into a leaf, a cloud, or any phenomenon, we are able to see its infinite lifespan in the ultimate dimension, and we realize that we are the same. If we look deeply enough, we will discover our own nature of no birth, no death. Like the Buddha, we also exist and can function in a much greater capacity than the ordinary frame of time and space we perceive ourselves to be bounded by.

We participate in the Buddha’s infinite life span and limitless spiritual strength when we are able to get in touch with the ultimate dimension of everything we see. When we are in touch with the Tathagata’s life span and spiritual power, we are also in touch with our own ultimate nature and spiritual power. Many of us go around all the time feeling that we are as small as a grain of sand. We may feel that our one small human life doesn’t have very much meaning. We struggle to get through life, and at the end of our life we feel that we have accomplished very little. This is a kind of inferiority complex many people suffer from. If we see reality only in terms of the historical dimension, it may seem to us as if there is little one ordinary human being can do. But if we get in touch with the ultimate dimension of reality, we know that we are just like the Buddha. We share in the Buddha’s nature – we are Buddha nature. When we are able to see beyond the limitations of perceived time and space, beyond our own notions of inferiority and powerlessness, we find we have great stores of spiritual energy to share with the world.

Taking the Bodhisattva Way

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p218In Chapter 2 of the Lotus Sutra we find such expressions as this:

If anyone, even while distracted,

With even a single flower,

Makes an offering to a painted image,

They will progressively see countless buddhas. (LS 94)If making an offering with just a single flower while being distracted can be a sign of taking the Buddha Way, surely such things as expressions of gratitude or apology, even superficial ones, can be signs of respect for others. Just as “merely formal” Dharma is better than no Dharma at all, small signs of respect are much better than no respect at all.

Never Disrespectful Bodhisattva tells everyone he meets, even extremely arrogant monks, even those who are angry, disrespectful, and mean-spirited, that they have taken the bodhisattva way. If what he says is true, surely whenever we make even superficial expressions of gratitude or apology, we are to some degree showing respect, a sign that, like Never Disrespectful Bodhisattva, we too have—to some slight but very important degree—taken the bodhisattva way that will lead to our awakening.

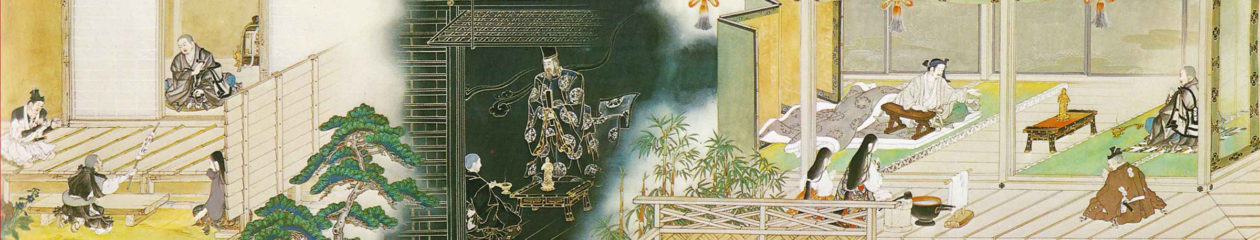

10 Divine Powers

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p224The divine powers displayed in this story are said to be ten in all, five having to do with the past and five with the future. The second five can be understood as consequences of the first five being widely implemented. While these ten are known as “divine powers,” they are actually events – events that display special, magical powers, some by buddhas, some by others.