Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p115The appearance of the Buddha in the historical dimension, as a particular person born into a particular family, and having a normal human life span, is like a magic show designed to capture the attention of the living beings of that time and guide them to the path of transformation. In the chapters of the Lotus Sutra discussed in Part One, on the historical dimension, the Buddha used various skillful means in teaching the paths of the three vehicles, when in fact there is really only One Vehicle. We could say that of all the Buddha’s methods of teaching, his appearance in the form of various historical Buddhas throughout time and space is the ultimate skillful means. Through this method, the Tathagata has never stopped teaching and guiding beings to liberation.

Category Archives: d21b

Our Misperception of the Buddha’s Lifespan

Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p115The Buddha says, “I have been living in this saha world for this great incalculable period of time, teaching the Dharma to innumerable living beings; and I have also been in an equally vast number of other world-spheres, teaching and helping beings.” The life span of the Buddha is not only spoken of in terms of time but also of space – immeasurable, infinite dimensions of time and space that are beyond the reach of intellectual conceptualization. So our idea of the Buddha as a purely historical person who lived 2,600 years ago, who passed into nirvana and is no longer able to be present with us here and now, is merely a misperception.

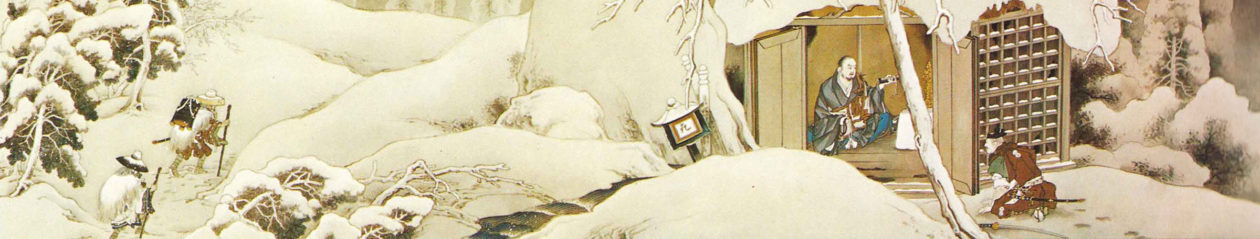

Other Mahayana sutras speak of the unborn and undying nature of the Buddha. For instance, the Vajracchedika Sutra says, “The Tathagata comes from nowhere and goes nowhere.” But in the Lotus Sutra, this truth is expressed in vivid images, like a beautiful painting, and for some it can be easier to understand and grasp through such visual imagery.

Generating a Spirit of Trust Toward the Teachings of the Lotus Sutra

Peaceful Action, Open Heart, p114The Buddha said to them, “My friends, you should trust and understand that the words spoken by the Tathagata are the truth. When I speak, I tell the truth and you must believe and understand my words.” The Sutra notes that the Buddha repeated this admonition three times. Because we do not hear the explanation right away, this scene serves to heighten the suspense. First, we have to trust the Buddha’s teaching. A Tathagata never utters a falsehood, never says anything that is not in accord with the truth. The Buddha’s word and person are in themselves a guarantee of the truth of his teachings, but there are those among the assembly who still feel some doubt, because what the Buddha has taught is not in accord with their own perception of things.

This detail is to show us that reasoning, concepts, and our general way of observing reality through our intellect only is a limited perception and it can be mistaken. So we should not be attached to ideas and concepts, we should not base too much on them. We may feel that what the Buddha teaches is quite unbelievable, but that is because our insight is not yet very deep. If we had deeper insight into the true nature of reality, as the Buddha does, we would be able to perceive things differently. We have to generate a spirit of trust toward the teachings, be willing to let go of our notions, and examine the teachings in the light of our practice of mindfulness.

Manifestations of the Lord Teacher Śākyamuni Buddha

It is preached in the “Life Span of the Buddha” chapter of the Lotus Sūtra, “The scriptures that I, the Buddha, expound are all for the purpose of emancipating all living beings. For this purpose I guide them in various ways, sometimes speaking of myself, sometime of others. Sometimes I present myself, sometimes others. Sometimes I show my own actions, sometimes those of others.”

Accordingly, who among the great beings — Zentoku Buddha of the World Without Worry to the east; the Great Sun Buddha in the center of the universe; various Buddhas in the worlds throughout the universe; the past seven Buddhas who appeared in this world; various Buddhas in the past, present, and future; the direct disciples of the Original Buddha who emerged from the earth such as Bodhisattva Superior Practice; bodhisattvas of theoretical teachings, such as Mañjuśrī, Śrāvaka disciples such as Śāriputra, the King of the Mahābrahman Heaven who controls the triple world; the King of Devils who lives in the Sixth Heaven in the realm of desire; Indra who controls the Trāyastriṃsá Heaven; or Sun Deity, Moon Deity, Deity of the Stars, innumerable stars such as the Great Bear, twenty-eight stars, Five Stars, Seven Stars and 84,000 Stars; those who occupy the headship of various places throughout the world such as the King of asura demons, god of the heavens, god of the earth, god of the mountains, god of the ocean, god of the house, and god of the village — is not a manifestation of the Lord Teacher Śākyamuni Buddha?

Nichigen-nyo Sakabutsu Kuyōji, Construction of a Statue of Śākyamuni by Lady Nichigen, Writings of Nichiren Shōnin, Followers II, Volume 7, Page 123-124

The Buddha and This Dangerous World

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p203-204We should notice that, as in the parable of the burning house of Chapter 3 of the Sutra, the dangers – the fire and many other terrible things in Chapter 3 and the poison in Chapter 16 – are found in the fathers’ houses. Some have raised questions as to why the Buddha would be so careless as to have such a fire-hazard of a house or why he would leave poison lying around in a house full of children. This kind of question probably presupposes that the Buddha is somehow all-powerful and creates and controls the world. But that is not a Buddhist premise. In the Dharma Flower Sutra the point of having the danger occur in the Buddha’s home is to indicate a very close relationship between the Buddha and this world. The world that is dangerous for children is the world in which the Buddha – like all of us – also lives. …

The parables in the Dharma Flower Sutra do not say that the fathers created the burning house or the poison found in the home of the physician. Shakyamuni Buddha has inherited this world, or perhaps even chose to live in this world, in order to help the living. The dangers in this world are simply part of the reality of this world. Indeed, it is because of them that good medicine and good physicians are needed here.

Problem Children

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p117In many stories in the Dharma Flower Sutra we find that characters who represent the Buddha have problems leading their children. In the early parable of the burning house, for example, the children in the burning house initially refuse to pay any attention to their father. Similarly, the children of the physician in Chapter 16 … also refuse to obey their father’s exhortation to take the good medicine he has prepared for them. The poor son in Chapter 4 is a runaway. In addition, we also often find sympathy being expressed for Shakyamuni Buddha because he is responsible for this world of suffering.

Collectively, both of these elements, disobedient children and sympathy from others, and many other things as well, point to the similarity of the Buddha to ordinary human beings. Some might think of the Buddha as being extremely distant and different from ourselves – along the lines of how the famous Christian theologian Karl Barth describes God: “totally other.” But in the Dharma Flower Sutra it is the opposite: the Buddha is very close to us, concerned about us, affected by us – thus similar to us. That is why the Buddha’s work, so to speak, is difficult. It is only because he cares about this world that his job is difficult.

We will often have the most difficulty leading those who are closest to us, our own children, or parents, or wives, or husbands. Often this can be a sign that things are as they can be. If life is difficult for the Buddha because he is close to the world, we should expect to have difficulties with those who are closest to us. Those difficulties should be taken as a sign that we should strive to improve our relationships with those closest to us, even though we can expect this to be difficult at times.

A Medicine Not Taken Is Not Yet Really Medicine

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p202This medicine is like the rain of the Dharma in Chapter 5, the same rain that goes everywhere to nourish all kinds of plants, but is received differently because people are different in their abilities, in what they like and dislike, and in their backgrounds. In other words, Buddha-medicine needs to be different for different people. What is important is to discern what medicine will actually work for someone. The medicine prepared for and given to the children is not really medicine at all for them until they actually take it. A medicine that is not taken, no matter how well prepared and no matter how good the intentions of the physician, is not effective, not skillful, not yet really medicine.

The same is true of the Buddha Dharma. It has to be taken or embraced by somebody, has to become real spiritual nourishment for someone, in order to be effective. Again, this is why in the Dharma Flower Sutra teaching is always a two-way relationship. Dharma is not the Dharma until it is received and embraced by someone. And, of course, people are different – so the Dharma has to be taught in a great variety of ways, using different stories, different teachings, poetry as well as prose, and so on.

The same is true of religious practices. For some Buddhists, meditation is effective; for others, recitation; for others, careful observance of precepts; for still others, sutra study; and so on. It is through an ample variety of teachings and practices that the Dharma has been effective and can be effective still. If we insist that there is only one proper way to practice Buddhism, it would be as if the physician in this story decided to let the children die because they did not immediately take the medicine he had offered.

Helping People Along Difficult Roads

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p94-95While there are several important things one might learn from this story [of the Magic City], its central message is quite clear: while we may think that nirvana, a condition of complete rest and quiet, is our final goal, it is not. While we may think that nirvana is salvation, that is only a useful illusion from which we will eventually need to move on. According to the Dharma Flower Sutra, it is always an illusion to think that we have arrived and have no more to do, to think that if we reach some kind of experience of happiness or comfort, we have reached the end of the path.

Similarly, while we may think that the Buddha entered final nirvana, becoming “extinct” and thus no longer active, that too is only a useful illusion, as the Buddha is working still, enabling us to live and work with him to save all the living. In Chapter 16 of the Sutra we can find these words:

In order to liberate the living,

As a skillful means I appear to enter nirvana.

Yet truly I am not extinct.

I am always here teaching the Dharma. (LS 296)The Buddha has used teachings, including the teaching of his own final nirvana, to help people along difficult roads.

The Enlightenment of the Three Types of Buddhas

Vasubandhu's Commentary on the Lotus Sutra, p 143-144The enlightenment of the three types of buddhas is explained in order to illustrate the supreme meaning of achieving great enlightenment.

First, [the supreme meaning of achieving great enlightenment] is illustrated by the enlightenment of the transformation buddha (nirmāṇakāya). [This type of buddha] manifests himself wherever he needs to be seen. Just as it says [in the chapter on “The Life Span of the Tathāgatas”] in the Lotus Sutra:

They all said the tathāgatas left the palace of the Śākyas, sat on the terrace of enlightenment not far from the city of Gayā, and attained highest, complete enlightenment.

Second, it is illustrated by the enlightenment of the enjoyment buddha (sambhogakāya), since the realization of permanent nirvana is attained by completing the practice of the ten stages. Just as it says in the Lotus Sutra:

O sons [and daughters] of good family! Countless and limitless, hundreds, thousands, ten thousands of myriads of kotis of world-ages have elapsed since I actually became a buddha.

Third, it is illustrated by the enlightenment of the absolute buddha (dharmakāya), “the tathāgatagarbha that is pure by nature and nirvana that is eternally permanent, quiescent, and changeless.” Just as it says in the Lotus Sutra:

The Tathāgata perceives all the aspects of the triple world in accordance with his knowledge of true reality. [He perceives there is no birth or death, no coming or going, no existence or extinction, no truth or falsehood, no this way or otherwise.] He does not perceive the triple world as those of the triple world perceive it.

“Aspects of the triple world” means that the realm of living beings is the realm of nirvana and that the tathāgatagarbha is not separate from the realm of living beings. “There is no birth or death, coming or going” refers to that which is permanent, quiescent, and unchangeable. Also, “no existence or extinction” refers to the essence of suchness of the tathāgatagarbha, which is neither [part of] the realm of living beings nor separate from it. ”No truth or falsehood, no this way or otherwise” refers to [true reality] being apart from the four marks [of existence] because that which possesses the four marks is impermanent. “He does not perceive the triple world as those in the triple world perceive it” means the buddhas, the tathāgatas, are able to perceive and able to realize the true absolute body, [even though] ordinary people do not perceive it. Therefore it says in the Lotus Sutra, “The Tathāgata clearly perceives [that which pertains to the triple world] without any delusion.”

“That the bodhisattva path I have previously practiced is even now incomplete” is due to his original vow, because his vow is incomplete as long as the realm of living beings remains unextinguished. “Incomplete” does not mean [that his] enlightenment is incomplete. “I furthermore have twice the number [of world-ages mentioned above] before my life span is complete.” This passage illustrates the Tathāgata’s eternal life, which through skill in expedient means is shown as an extremely great number. [That his life span] surpasses the number above means that it is countless.

“My pure land does not decay yet living beings perceive its conflagration” means the true pure land of the enjoyment buddha, the Tathāgata, is incorporated in the highest truth.

Living the Bodhisattva Way

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p206Various reasons are given in the Sutra as to why the Buddha has announced his entry into final nirvana when actually he is still alive in this world. For example: “If the Buddha lives for a long time in this world, people of little virtue will not plant roots of goodness, and those who are poor and of humble origins will become attached to the five desires and be caught in a net of assumptions and false views. If they see that the Tathagata is always alive and never extinct, they will become arrogant and selfish or discouraged and neglectful. Unable to realize how difficult it is to meet him, they will not have a respectful attitude toward him.” (LS 293)

It is useful to understand these terms through the vehicle of the parables. The children in the parable of the burning house are too absorbed in their play to notice what is going on around them, including their father’s attempts to warn them of the dangers. The son in the parable of the rich father and poor son is simply lacking in self-confidence and self-respect. The children in this parable are stricken by poison. All are in need of help and guidance, but what they need guidance for is to accept greater responsibility for the direction and quality of their own lives. In this way, they can, perhaps only very gradually, become bodhisattvas, and take responsibility for doing the Buddha’s work in this world.

And yet, even though stories have been told about the death of the Buddha, even now the Buddha is not really dead. He is still with us, alive in this world, living the bodhisattva way, doing the bodhisattva work of transforming people into bodhisattvas and purifying buddha lands. “From the beginning,” he says, “I have practiced the bodhisattva way, and that life is not yet finished. . . .” (LS 293)