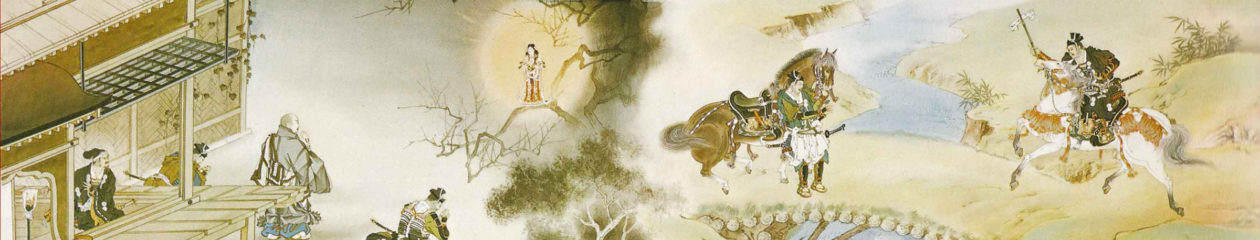

In considering the lessons of Chapter 15, The Appearance of Bodhisattvas from Underground, we normally start with something like this from Rev. Ryusho Jeffus’ Lecture on the Lotus Sutra:

Lecture on the Lotus Sutra“We each may think we are rather ordinary people, not capable of great things. Yet our ordinariness is in fact a disguise for our true self, Bodhisattvas from beneath the ground, the disciples of the Buddha from the infinite past, and beings perfectly endowed with Buddhahood.”

For those new in faith, that may be challenging. Still more difficult is the idea of a place in the sky below this world. I’ve facetiously suggested the sky above Melbourne, Australia, but the question is worth serious consideration. In Stories of the Lotus Sutra, Gene Reeves addresses the ambiguity of the hiding place:

The Stories of the Lotus Sutra, p189“Exactly what is meant by the empty space below the earth is unclear. … The dramatic effect of the story is dependent on the existence of these bodhisattvas being unknown to all but Shakyamuni, so they have to be hidden somewhere. But it is also important for the thrust of the story that they not be from some other world, or even from one of the heavens or purgatories associated with this world. In other words, both for the sake of the story and for the sake of the central message of the Dharma Flower Sutra, it is important that these bodhisattvas be both hidden and somehow of this world. Thus the Buddha says, ‘They are my children, living in this world…’ .”

Nikkyō Niwano has an interesting alternative take in Buddhism for Today:

Buddhism for Today, p179“That these bodhisattvas [from Underground] did not originally dwell in the earth but that they, who were in the infinite space below the sahā-world, came out of the earth and rose into the sky has a deep meaning. These bodhisattvas were people who had been freed from illusion in their previous lives by means of the Buddha’s teachings. For this reason, they had been dwelling in infinite space. But hearing the Buddha declare that he would entrust the instruction of the sahā-world to them, they entered into the earth, namely, this sahā-world, experiencing suffering there, and practiced religious disciplines so zealously as to attain the mental state of bodhisattvas. Therefore, they rose into the sky again after coming out of the earth. Though the bodhisattvas had been free from illusion in their previous lives, they voluntarily passed through various sufferings and worries in sahā-world for the purpose of saving the people here, endeavored earnestly to become enlightened, and preached the teaching to others. As mentioned before, this is a very important process; without completing such an endeavor, they could not truly acquire the divine power to save the people in the sahā-world.”

Ordinary people or extraordinary beings, we have a job. As Ryusho Jeffus says in his Lecture on the Lotus Sutra:

Lecture on the Lotus Sutra“At the heart of Buddhism is making great effort at practicing and changing our lives, something that does not happen without concerted continued effort.”

Table of Contents Next Essay