Two Buddhas, p 157Nichiren maintained that the Lotus Sūtra enables women to attain buddhahood as women, because it embodies the mutual encompassing of the ten dharma realms. He writes: “The other Mahāyāna sūtras would seem to permit women to attain either buddhahood or birth in the pure land [of Amitābha], but that is an attainment premised on changing their [female] form, not the direct manifestation of buddhahood grounded in the three thousand realms in a single thought-moment. Thus, it is an attainment of buddhahood or pure land birth in name but not reality. The nāga girl represents the ‘one example that applies to all.’ Her attainment of buddhahood opened the way for the attainment of buddhahood … by all women of the latter age.”

Category Archives: d17b

Opportunities to Further Religious Development

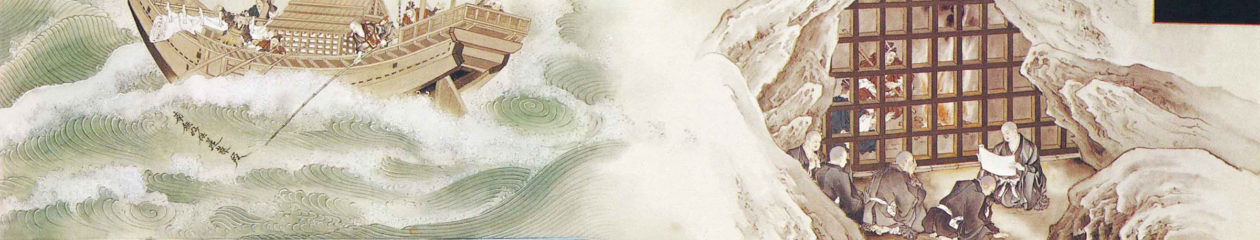

Two Buddhas, p146Nichiren wrote that the gohonzon represents the Lotus assembly “as accurately as the print matches the woodblock.” On it, all ten realms, even the lowest ones, are represented. We find the belligerent asura king; the dragon king, representing the animal realm; the demon Hāriti (J. Kishimojin); even the Buddha’s malicious cousin Devadatta, who tried to kill him on multiple occasions; and Devadatta’s patron, King Ajātaśatru, who murdered his father and supported Devadatta in his evil schemes. As Nichiren wrote, “Illuminated by the five characters of the daimoku, all ten realms assume their inherent enlightened aspect.” We might interpret this as reflecting Nichiren’s message that, through the chanting of the daimoku, even life’s harsh, ugly, and painful parts — the most adverse circumstances, or the darkest character flaws — can be transformed and yield something of value, becoming opportunities to further religious development.

Deadly Poison Turning Into Nectar

Besides the Three Pronouncements made in the “Appearance of the Stupa of Treasures” (11th) chapter of the Lotus Sūtra, the Buddha issued two more proclamations in the following twelfth chapter, “Devadatta,” of the same sūtra with the intention of having it spread after His death. Devadatta had been regarded as a man of the icchantika who did not have any possibility of attaining Buddhahood. He, nevertheless, was assured by the Buddha of becoming Tennō (Heavenly King) Buddha in the future. The forty-fascicled Nirvana Sūtra has stated the existence of the Buddha-nature in all, which is realized in this “Devadatta” chapter. Numerous offenders such as Zenshōbiku (Sunakṣatra) and King Ajātaśatru committed the Five Rebellious Sins or slandered the True Dharma. Since the worst of them, Devadatta, was assured of becoming a Buddha in the future, all others would naturally be assured just as people follow the leader and twigs and leaves join a tree. That is to say the example of Devadatta assured of being the future Heavenly King Buddha has made it unmistakable that all offenders of the Five Rebellious Sins or Seven Rebellious Sins, slanderers of the True Dharma, and men of icchantika – all of them will attain Buddhahood someday. This is somewhat like deadly poison turning into “nectar,” the best of all flavors.

Kaimoku-shō, Open Your Eyes to the Lotus Teaching, Writings of Nichiren Shōnin, Doctrine 2, Page 90

Giving One’s Life for the Lotus Sūtra

Two Buddhas, p227-228[T]he Lotus Sūtra seems to urge giving one’s life in its service. Bodhisattvas in the “Perseverance” chapter vow that they “will not be attached to our bodies or lives,” and the “Lifespan” chapter says that the primordial Śākyamuni Buddha will appear before those beings who “are willing to give unsparingly of their bodies and their lives.” How should such passages be understood?

Nichiren addresses this issue in a letter to a disciple, the lay nun Myōichi-ama, expressing sympathy on the death of her husband, who had held fast to his faith despite great difficulties: “Your late husband gave his life for the Lotus Sūtra. His small landholding that barely sustained him was confiscated on account of [his faith in] the Lotus Sūtra. Surely that equaled ‘giving his life.’ The youth of the Snow Mountains [described in the Nirvāṇa Sūtra] offered his body in exchange for half a verse [of a Buddhist teaching], and the bodhisattva Medicine King [Bhaiṣajyarāja] burned his arms [in offering to the Buddha]. They were saints, [and for them, such acts were] like water poured on fire. But your husband was an ordinary man, [and so for him, this sacrifice was] like paper placed in fire. When we take this into consideration, his merit must surely be the same as theirs.”

Evil Persons Attaining Buddhahood

Two Buddhas, p 155-156According to conventional Buddhist thinking, moral conduct is the beginning and foundation of the path; persons can achieve liberation only by first renouncing evil and cultivating good. It is said that one cannot control one’s mind until one first learns to control one’s body and speech. The Buddhist ethical code seeks to provide such control. However, some Buddhist thinkers in Nichiren’s time were concerned with the problem posed by evils that one cannot avoid. This concern had to do with a keen awareness of human limitations, heightened by a sense of living in an age of decline. It also spoke to the situation of warriors, who were gaining influence both as a social group and as an emergent body of religious consumers. From a Buddhist perspective, warriors were trapped in a hereditary profession that was inherently sinful, requiring them to kill animals as a form of war training and kill humans on the battlefield. Thus, they could not escape violating the basic Buddhist precept against taking life. Nichiren, who had a number of samurai among his followers, stressed that, as long as one chants the daimoku, one will not be dragged down into the hells or other evil paths by ordinary misdeeds or unavoidable wrongdoing. To one warrior, a certain Hakii (or Hakiri) Saburō, he wrote: “In all the earlier sūtras of the Buddha’s lifetime, Devadatta was condemned as the foremost icchantika in all the world. But he encountered the Lotus Sūtra and received a prediction that he would become a tathāgata called Devarāja. … Whether or not evil persons of the last age can attain buddhahood does not depend upon whether their sins are light or heavy but rests solely upon whether or not they have faith in this sūtra.”

Could Lotus Sūtra Words Prove To Be Empty?

If those words of the sūtra prove to be empty, Venerable Śāriputra will not be Flower Light Buddha, as stated in the Lotus Sūtra. Likewise, Venerable Kāśyapa will not be Light Buddha, Venerable Maudgalyāyana will not be Tamalapatra-candana Fragrance Buddha, Ānanda will not be Mountain Sea Wisdom Supernatural Power King Buddha, Bhikṣunī Mahā-Prajāpatī will not be Gladly Seen by All Living Beings Buddha, and Yaśodharā will not be Endowed with Ten Million Glowing Marks Buddha. The teaching of the “3,000 dust-particle kalpa” expounded in the “Parable of Magic City” chapter will be a useless discussion; and that of the “500 (million) dust-particle kalpa” in “The Life Span of the Buddha” chapter will be a lie. Probably Lord Śākyamuni will fall into the Hell of Incessant Suffering; the Buddha Many Treasures will be burnt in the fire in the Hell of Incessant Suffering; Buddhas in manifestation in all the worlds in the universe will fall into the eight horrible hells; and all the bodhisattvas will be tortured with 136 kinds of torment. How could such things happen? They will never happen, as I am sure that all the people in Japan will come to chant “Namu Myōhōrengekyō.”

Hōon-jō, Essay on Gratitude, Writings of Nichiren Shōnin, Doctrine 3, Pages 58-59.

Implicit and Explicit Predictions

In Chapter 13, the predictions for Maha-Prajapati Biksuni and Yasodhara Biksuni come about in an indirect sort of way. The Buddha notices his aunt, the woman who raised him after his mother died in child birth, looking at him. I can just imagine it to be one of those looks only a mother could give a child, something on the order of a scolding without words. This would be a look that probably told the Buddha, hey aren’t you forgetting something.

At any rate the Buddha guesses what his aunt is thinking and asks her if she thought that somehow she had been left out of all the predictions that have now covered every practitioner type, Sravakas, Pratyekabuddhas, Bodhisattvas. He says he had already assured the Sravakas of their enlightenment and that he did not exclude her from that general grouping. In this I believe the Buddha realizes that even though he had implicitly included women in the general prediction, he realizes now that the women really need it clearly stated not just for them but for the males in the congregation.

Lecture on the Lotus SutraThe Lesson of the Dragon King’s Daughter

The story of how the Dragon-King’s daughter attained enlightenment [in Chapter 12, Devadatta,] has long been taken as an example of women attaining enlightenment by instantly understanding the Dharma. In India, it was thought that women were spiritually inferior to men, and could not enter any of the five superior existences–Buddhahood being one of them. However, Sakyamuni taught that all living beings–male or female, young or old, human or nonhuman–are potential Buddhas. This story graphically illustrates his point, and it helped future generations overcome their prejudice against women.

Introduction to the Lotus SutraThe Dragon Girl’s Example

The Buddha is a perfected being with a human personality. He is the ideal toward which all human beings strive. It had long been believed that to become such a perfect being takes an endlessly long period of training and practice. But [in Chapter 12, Devadatta,] the daughter of the Dragon-King attained enlightenment quickly. Her case is called, “The Attainment of Buddhahood in This Very Life.” It maintains that ordinary people have the possibility to attain enlightenment in their own bodies (during their present lifetimes), and teaches that the Buddha’s power works within the bodies of ordinary people. The idea of “the attainment of Buddhahood in this life” greatly influenced Japanese society after the Great Master Dengyo introduced it from China in 805. Dengyo, a Japanese scholar, had already read about it in the Lotus Sutra, but he found that the Chinese had worked it out in detail. Also, Nichiren explained this idea in Kanjin-honzon-sho (“A Treatise Revealing the Spiritual Contemplation of the Most-Venerable-One”). In it he says, “Sakyamuni Buddha, who has attained Perfect Enlightenment, is our flesh and blood, and all the merits he has accumulated before and after attaining Buddhahood are our bones.”

Introduction to the Lotus SutraKneeling Before the Buddha

Devadatta is known as a very bad person. Once he attempted to murder Sakyamuni. It is said that he was the elder brother of Ananda, Sakyamuni’s cousin, who was the famous reciter of his teachings. This makes Devadatta a close relative of Sakyamuni.

Since childhood, however, Devadatta had been jealous of his extraordinary cousin. After becoming a monk himself, he became arrogant, and plotted to take over the leadership of Sakyamuni’s movement. When that failed, he withdrew and started a counter-movement of his own. Finally he decided to murder the Buddha. One day as Sakyamuni was entering the city of Rajagriha, Devadatta let loose in his path a mad elephant, hoping it would trample the Buddha to death. However, a popular story relates that the plan did not work. The elephant terrified people on the streets, and sent them flying in all directions for safety. But when it saw Sakyamuni, it suddenly stopped, and kneeled before him.

Introduction to the Lotus Sutra