The story of Devadatta is well-known. He was a very bright and highly charismatic monk who, because of his ambition, brought about a schism in the Sangha. Devadatta first tried to get the Buddha to appoint him leader of the Sangha. The Buddha was then over seventy years old, near the end of his life and ministry. But while he considered himself to be a teacher and an inspiration, the Buddha didn’t think of himself as the leader of the Sangha, and he didn’t want to appoint someone as a leader, either. So he refused Devadatta’s request.

Devadatta then allied himself with Prince Ajātaśatru, King Bimbisara’s son, and the two schemed to usurp the kingdom so that Ajātaśatru could ascend the throne and Devadatta could gain control of the Sangha. Devadatta went before an assembly of the Buddha’s Sangha and proposed a set of ascetic guidelines for the monks, trying to show that his way of practice was more serious and austere. The Buddha did not accept these new guidelines for the Sangha but said that any monk who wished to practice them was free to do so. Devadatta was highly charismatic, and he was able to persuade nearly 500 monks to join his new Sangha. Many of these monks were young and had not yet had much opportunity to learn from the Buddha.

In this way, Devadatta brought about the first schism of the Buddhist Sangha. He and his group went to live on Mount Gayashisa, and Ajātaśatru supported them with donations of food and medicine. Then Ajātaśatru initiated his plan to take over the kingdom. After an attempt on his father’s life was unsuccessful, he had his father put under house arrest and deprived him of food so that he would starve to death. Queen Vaidehi, wife of Bimbisara and Ajātaśatru’s mother, visited her husband every day, hiding food on her person, and for a while she was able to keep the king nourished. But her subterfuge was discovered, and Ajātaśatru barred her from seeing the king. The king eventually died in confinement. The Buddha’s personal physician, Jīvaka, also served Queen Vaidehi. Through Jīvaka, the Buddha learned of Ajātaśatru’s schemes and that Devadatta was behind them.

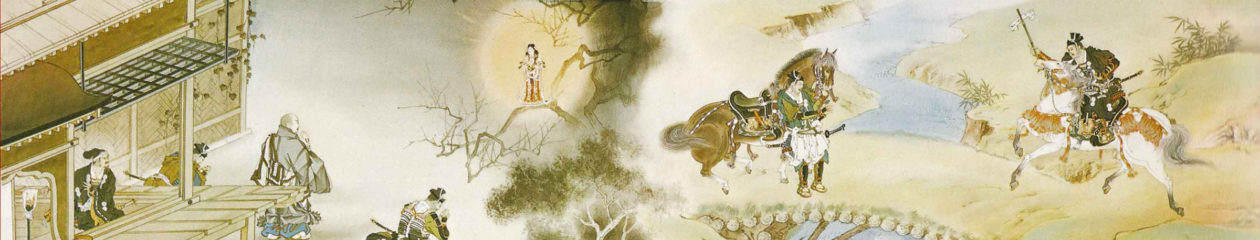

Devadatta was also behind three attempts on the Buddha’s life. The first time a swordsman was sent to assassinate him. But when he saw the Buddha sitting in meditation in the moonlight, he was not able to carry out the murder. Instead he knelt before the Buddha and confessed. According to the plan, once he had killed the Buddha, the assassin was to leave the mountain by a certain path, unaware that he himself would be killed in order to cover up the murder. So the Buddha advised him to go down a different path and then, with his mother, flee to the neighboring kingdom of Kosala for refuge.

In the second attempt, the would-be murderers rolled a big boulder down from the mountaintop. The stone struck the Buddha, and though it did not kill him, his left foot was badly wounded and he lost a lot of blood. In the third attempt, Devadatta’s men released a wild elephant to attack the Buddha, but the Buddha was able to calm the animal and was not harmed. The Buddha survived all three attempts on his life and he did not leave the kingdom, even though it was a very difficult time for him. He continued to stay and practice there, and through the practice, he exemplified nonviolent resistance.

Eventually, with the help of the bhikshus Śāriputra and Maudgalyāyana, who visited Devadatta’s Sangha to teach and help the young monks, nearly everyone returned to the Buddha and the schism in the Sangha was healed. Later on Devadatta became very sick and was near death. He was so weak and ill that he could not stand or walk on his own anymore, so he asked two monks to carry him to The Gṛdhrakūṭa Mountain Peak. There, before the Buddha, Devadatta said, “1 take refuge in the Buddha, I go back to the Buddha and take refuge in him,” and the Buddha accepted him back into the Sangha.

Sometime later, Ajātaśatru was also struck down, by a mental illness. He was filled with remorse and afflicted in body and mind because he had killed his own father and had done many bad things in order to gain power. He consulted various teachers and healers, but no one could cure him. Finally, he consulted with Jīvaka, who advised him to go directly to the Buddha. Ajātaśatru was ashamed. He said, “I cannot go to the Buddha. He must be very angry with me!” But Jīvaka assured him, “No, the Buddha has a lot of compassion, he is not angry with you. If you go to him and ask him with all your heart, he will help you overcome this illness.”

Jīvaka arranged for Ajātaśatru to attend a Dharma talk by the Buddha in the Mango Grove at the foot of The Gṛdhrakūṭa Mountain Peak. The Buddha spoke on the fruits of the practice, and after the talk the king was invited to ask a few questions. The Buddha took this opportunity to undo the knots within Ajātaśatru and help him recover his health. That day the Buddha served as a skillful physician, a wise and patient psychotherapist to the king, and a good relationship between them was restored. In fact, in the opening scene of the Lotus Sutra we learn that Ajātaśatru is also in the audience, a detail that tells us the Sutra was delivered toward the end of the Buddha’s life, and which shows that Ajātaśatru had returned to the family of the Buddha. From the stories of Devadatta and Ajātaśatru we can see how great is the Buddha’s power of inclusiveness, tolerance, and patience. Even though these two men had committed the worst possible offenses, through his love and compassion the Buddha was able to help them transform and rejoin the family of humanity.