Yes, people do pray to Kwan-yin for help, and Kwan-yin takes on whatever form is needed to be helpful. But while that story may present the hope of divine blessing, it is there primarily to show us what we should be. If Kwan-yin has a thousand arms with a thousand different skills with which to help others, we too need to develop a thousand skills with which to help others. This is the chief significance of the inclusion of the Kwan-yin chapter in the Lotus Sutra. It is there to encourage bodhisattva practice.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 194

Category Archives: Kaleidoscope

Appropriate Means To Be a Bodhisattva

What, then, does it mean to be a bodhisattva? Basically, in the Lotus Sutra it means using appropriate means to help others. And that, finally, for the Lotus Sutra, is what Buddhism itself is. It is an enormous variety of means developed to help people live more fulfilling lives, which can be understood as lives lived in the light of their interdependence. This is what many of its stories are about: someone – a father-figure/buddha, or friend/buddha, or guide/buddha – helping someone else gain more responsibility for their own lives.

Even if you search in all directions,

There are no other vehicles,

Except the appropriate means preached by the Buddha.

Thus, the notion of appropriate means is at once both a description of what Buddhism is, or what Buddhist practice primarily is, and a prescription for what our lives should become. The Lotus Sutra, accordingly, is a prescription of a medicine or religious method for us — and, therefore, at once both extremely imaginative and extremely practical.

It is in this sense that appropriate means is an ethical teaching, a teaching about how we should behave in order to contribute to the good. It is prescriptive not in the sense of a precept or commandment, but in the sense of urging us, for the sake both of our own salvation and that of others, to be intelligent, imaginative, even clever, in finding ways to be helpful.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 194

Buddha-Nature

While the term “buddha-nature” does not appear anywhere in the Lotus Sutra, the teaching of what would later be called buddha-nature runs through it like a cord, defining one of its central affirmations. It is a clear aim throughout the sutra to persuade the reader that every living being, including and most importantly the reader, has within a potential to become enlightened, to become a buddha.

One’s buddha-nature is developed by following the Buddha-way, doing what buddhas have always done, bodhisattva practice. Central to the Lotus Sutra is the idea that Śākyamuni Buddha himself is, first of all, a bodhisattva. He has been doing bodhisattva practice, helping and leading others, for innumerable kalpas, and will continue to do so into the boundless future.

Because all the living have various natures, various desires, various activities, various ideas and ways of making distinctions, and because I wanted to lead them to put down roots of goodness, I have used a variety of explanations, parables, and words and preach various teachings. Thus I have never for a moment neglected the Buddha’s work.

Thus it is, since I became Buddha a very long time has passed, a lifetime of unquantifiable asamkhyeya kalpas, of forever existing and never entering extinction. Good children, the lifetime which I have acquired pursuing the bodhisattva-way is not even finished yet, but will be twice the number of kalpas already passed.

While it is very important that the Buddha and the śrāvakas are also in some sense bodhisattvas, it is even more important that you and I are bodhisattvas — called to grow in bodhisattvahood by leading others to realize that potential in themselves. To develop one’s buddha-nature is to do bodhisattva practice, to follow the role model of the bodhisattvas.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 193

Lifetime Beginners

What the sutra condemns is not other people, and not the lesser vehicles, but arrogance — especially the arrogance of thinking one has arrived at the truth, at some final goal. Rather, we are called upon by this sutra to be “lifetime beginners,” people who know they have much to learn and always will. The five thousand who walk out of the assembly in the second chapter are said to be like twigs and leaves and not really needed, but in chapter 8 they too are to be told that they will become buddhas.

Thus śrāvakas are also bodhisattvas. In every paradise, or paradise-like Buddha-land, there are countless śrāvakas, indicating that the śrāvaka-way is not to be rejected or discarded, but relativized, seen within a larger context, which is the encompassing Buddha-way. Many śrāvakas, of course, do not know that they are bodhisattvas, but they are nonetheless. The Buddha says to the disciple Kāśyapa at the end of chapter 5:

What you are practicing Is the bodhisattva-way.

As you gradually practice and learn,

Every one of you should become a Buddha.

The Only Reason Buddhas Come into the World

In the first chapter heavenly flowers fall on both the Buddha and his listeners, indicating the equality of both. That idea is extended in chapter 3 with the idea that the Buddha preaches only to bodhisattvas. The point is that to preach the Dharma is to be a bodhisattva — and to hear the Dharma is to be, to that degree, a bodhisattva. This is because really hearing is to take it into one’s life, thus to practice it, thus to be a bodhisattva. Thus, it can be said that the buddhas come into the world only to transform people into bodhisattvas.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 192

Appropriate Devices

Sometimes the Buddha has to use appropriate devices in order to lead others to realize their potential. But this does not mean that any trick will do. The Buddha’s devices are always appropriate – i.e., designed for the benefit of the recipient. The father thought about what would be appropriate for these particular children in this particular situation.

Even the very fancy cart which the father gives to the children is, after all, only a cart, a vehicle. All teachings and practices should be understood as devices, as possible ways of helping people. They should never be taken as final truths. But the fact that they can be and are used to save people means that they are very important truths, that is, sufficient to save people.

Thus in the Lotus Sutra, teaching is not teaching, or at least it is not

Dharma teaching, unless someone is taught.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 192

The Burning Playgrounds

[The Parable of the Burning House] is interpreted as saying that the world is like a burning house. But the idea of escaping from the world is not what the sutra teaches. Elsewhere it makes clear that we are to work in the world to save others. The point here, I think, is more that we are like children at play, not paying enough attention to the environment around us. Perhaps it is not the whole world that is in flames, but our playgrounds, the private worlds we create out of our attachments and out of our complacency. Thus, leaving the house is not escaping from the world but leaving behind our play-world, our attachments and illusions, or some of them, in order to enter a real world.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 191

The Many Paths Within the Great Path

Parables are analogies, but never perfect ones. [The Parable of the Burning House] provides an image of four separate vehicles. But if we follow the teaching of the sutra as a whole, the One Buddha Way is not an alternative to other ways; it includes them. A limitation of this parable is that it suggests that the diverse ways (the lesser carts) can be replaced by the One Way (the special cart). But the overall teaching of the sutra makes it plain that there are many paths within the Great Path, which integrates them, i.e., they are together because they are within the One Way. To understand the lesser ways as somehow being replaced by the One Way would entail rejecting the whole idea of the bodhisattva-way, which the sutra clearly does not do. In fact, the whole latter part of the sutra is a kind of extolling of the bodhisattva-way. Also, in the story itself, in running out of the burning house the children are pursuing the śrāvaka, pratyekabuddha, and bodhisattva ways. In terms of their ability to save, the three ways are essentially equal. They all work.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 191

Learning from Difficulties

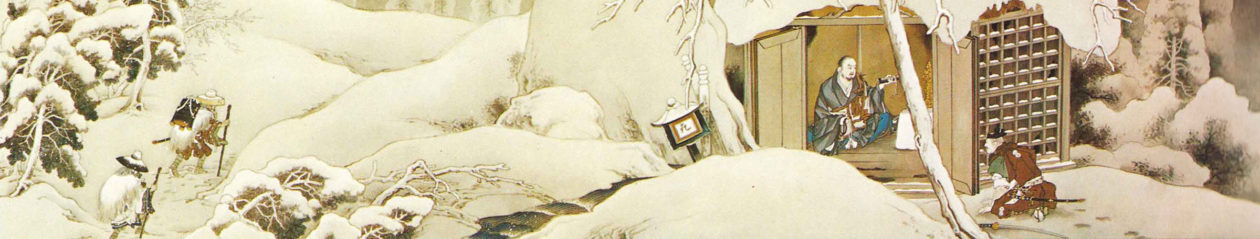

Here [in the story about Wonderful Voice Bodhisattva’s visit] again is expressed the idea that the sahā world, despite its obvious shortcomings, is something special, and that this is related to the presence in it of Śākyamuni Buddha. There may be other reasons for this, but I suppose that the great size and magnificence and accomplishments of the Bodhisattva Wonderful Voice contribute to the enhancement of the sahā world and Śākyamuni, since he comes to the sahā world to pay tribute to Śākyamuni Buddha.

In fact, there seems to be an implication here, and in other instances where bodhisattvas come from outside the sahā world to visit Śākyamuni Buddha, that the sahā world is especially important because it is a more appropriate, that is, more difficult, place for bodhisattva practice. One of the repeated themes of the sutra is that one can and should learn from difficulties. Salvation, in this world, is not a matter of freedom from suffering and distress, but rather an ongoing process of overcoming evil by helping others. In this sutra, for example, Śākyamuni Buddha simply thanks Devadatta, well known elsewhere as the personification of evil, for being his teacher, and predicts that Devadatta too will become a buddha. In this sense, this world offers many opportunities for one to enter the Buddha-way through bodhisattva practice.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 188-189

The Significance and Magnificence of Śākyamuni Buddha

In chapter 16, the Buddha has made clear that he is alive at all times and, in this sense, universal or eternal. In chapter 17, having heard this, an incredibly large number of living beings, bodhisattvas, and bodhisattva mahāsattvas receive various blessings, such as the ability to memorize everything heard, unlimited eloquence, power to turn the wheel of the Dharma, supreme enlightenment after eight, four, three, two or one rebirths, or the determination to achieve supreme enlightenment. In all twelve different groups within the congregation assembled to hear the Buddha preach are mentioned here, each of them enormously large, and each having received various blessings as a consequence of hearing about the everlasting life of the Buddha.

In response to this joyous occasion, the gods in heaven(s) rained beautiful flowers and incense down on the innumerable buddhas of the ten directions who had assembled in the sahā world, on Śākyamuni Buddha and Many Treasures Buddha, then sitting together in the latter’s magnificent stupa, and on the great bodhisattvas, and on the monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen assembled there. Deep in the sky, wonderful sounding drums reverberated by themselves. The many Indras and Brahmas from the other Buddha-lands came. Then the gods rained all kinds of heavenly jewel-encrusted garments in all directions, and burned incense in burners which moved around the whole congregation by themselves. And above each of the buddhas assembled under the great jeweled trees, bodhisattvas bearing jeweled streamers and such, and singing with wonderful voices, lined up vertically, one on top of the other, all the way to the heaven of Brahma.

Clearly the events depicted here are both magical and cosmological in scope. The story involves countless worlds, buddhas, bodhisattvas, and wondrous events with flowers, sound, and incense — all in praise of the revelation, in the sahā world, of the good news of the Buddha’s ever-presence. Within the story it is, in a sense, important that there are many worlds in ten directions, and gods as well as buddhas, bodhisattvas, and humans. But, in another sense, how many directions there are, or how many different kinds of beings there are, has virtually no importance. In fact, here and I think only here, the text refers to nine directions, rather than the usual ten. What is important is that no matter how many directions there are, no matter how many worlds there are, and no matter how many kinds of living beings there are, all are delighted and transformed by and extol the ever-presence of the Buddha — the fact that none of them ever is or ever was or ever will be without the presence of the Buddha. The story uses a cosmological setting, but it does so for the purpose of proclaiming the significance and magnificence of Śākyamuni Buddha, the Buddha of the sahā world.

A Buddhist Kaleidoscope; Gene Reeves, The Lotus Sutra as Radically World-affirming, Page 186-187