History and Teachings of Nichiren Buddhism, p 104-105The sūtra classification system of the Lotus Sūtra explains how it differs from other sūtras. This system is called the “three standards of comparison,” which measure the worth of a teaching. The first measure is whether people of all capacities can attain buddhahood through a particular sūtra. The second is whether the process of teaching is revealed in full. The third standard is whether the original relationship between teacher and disciples is revealed. The five periods and eight teachings are treated as exemplifying the first standard of comparison.

Category Archives: history

Five Flavors of the Poor Son’s Instruction

History and Teachings of Nichiren Buddhism, p 104[T]he five flavors Zhiyi used to classify the Buddha’s teachings correspond to the five sequential events from the parable of the prodigal son in Chapter 4 of the Lotus Sūtra. These five events are providing, inviting, encouraging, purifying, and revealing.

- Providing is the period of the Flower Garland Sūtra when Śākyamuni Buddha tested sentient beings to see if they would accept the Dharma. In the parable, this corresponds to bringing the prodigal to his family home.

- Inviting is the period of the Deer Park teachings when the Buddha preached the Hinayāna teaching to the śrāvakas and pratyekabuddhas, who did not at first understand, in order to invite them in. In the parable, letting the prodigal do menial cleaning work.

- Encouraging, also understood as admonishing, is the period of the Expanded teachings when the Buddha guided śrāvakas and pratyekabuddhas who were satisfied with Hinayāna teachings, to move on to Mahāyāna teachings. In the parable, promoting the prodigal to more responsible and prestigious positions and acclimating him to life in the mansion.

- Purifying is the period of the Wisdom teachings when the Buddha expounded the only true teaching by reconciling disagreements between Hinayāna and Mahāyāna. In the parable, entrusting the prodigal with managing the estate.

- Revealing is the period of the Lotus and Nirvāṇa Sūtras when the Buddha preached the ultimate teaching. In the parable, announcing that the prodigal is in fact his son and heir.

Five Flavors

History and Teachings of Nichiren Buddhism, p 103-104The five flavors are from a metaphor preached in the Nirvāṇa Sūtra: “As fresh milk comes from a cow, cream from the fresh milk, butter curds from cream, fresh butter from butter curds, and clarified butter from fresh butter, so is the teaching of the Buddha.” The sūtra uses this metaphor to explain the development of the teaching of the Buddha through the twelve-fold scriptures, the Agama sūtras, the Expanded sūtras, the Wisdom sūtras, and the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra. Zhiyi further utilized this five-flavor theory to explain the five periods by applying that classification — Flower Garland, Deer Park, Expanded, Wisdom, and Lotus/ Nirvāṇa. — to reflect the sequence of the teaching and growing maturity of the capacities of the listeners.

The Buddha’s True Intention

History and Teachings of Nichiren Buddhism, p 103In the Lotus Sūtra, the Buddha revealed his true intentions. The teachings of the previous forty years used skillful means for śrāvakas, pratyekabuddhas, and bodhisattvas in accordance with their capacities. However, the Trace Gate of the Lotus Sūtra tells us that only the One Vehicle leads people to the true teaching for awakening. The Original Gate of the Lotus Sūtra teaches that the duration of the Buddha’s life is eternal.

For those who could not listen to the Lotus Sūtra, the Nirvāṇa Sūtra was expounded to them so they could “awaken to the Lotus.” It was taught to extend awakening to those who had been left out during the exposition of the Lotus Sūtra. Hence, it is also called the teaching of “gleaning.”

Tiāntái’s Five Periods

History and Teachings of Nichiren Buddhism, p 101-103

- 1. THE FIRST PERIOD: THE FLOWER GARLAND SUTRA

- This is the twenty-one day period following Śākyamuni’s enlightenment, during which he verified his awakening. Beneath the Bodhi Tree, the Buddha manifested as Vairocana and taught the Flower Garland Sūtra to the Bodhisattvas of the Dharma-body who had practiced sufficiently in their previous lives. Although Universal Worthy Bodhisattva and Mañjuśrī Bodhisattva understood his teaching, those with inferior capacities did not.

- 2. THE SECOND PERIOD: THE DEER PARK TEACHINGS

- After he became certain of his awakening, Śākyamuni left the Bodhi tree and went to Deer Park in modern day Benares. There he taught the Hinayāna teaching to five monks, or bhikṣu, including Ājñāta-Kauṇḍinya. Over the next twelve years, he taught the Agama sūtras to the people according to their capacities: the four noble truths to the śrāvakas, the twelve-fold chain of dependent origination to the pratyekabuddhas, and the six perfections to the bodhisattvas. Although he taught at locations other than Deer Park, this period is called the Deer Park period, as that is where he first began preaching the Agama sūtras.

- 3. THE THIRD PERIOD: THE EXPANDED TEACHINGS

- The Period of Expanded Teaching lasted eight years. In Sino-Japanese this period is called “Hōdō.” Hō, means wide, and in this period the teachings of both Mahāyāna and Hinayāna were taught, so the teachings were widened or expanded. Dō, or tō, means equal. The teachings of Hinayāna and Mahāyāna were taught to people equally, according to their capacities. Only the Mahāyāna teaching was taught during the first period and only the Hinayāna teaching during the second period, but this third period links Hinayāna and Mahāyāna, so this teaching is also called the “common” teaching. By comparing Hinayāna and Mahāyāna, people found the Mahāyāna teaching within the Hinayāna teaching, and people therefore learned Mahāyāna Buddhism. Sūtras expounded in this period included the Vimalakīrti Sūtra, Questions of Brahma Excellent Thought Sūtra, Entering Laṇkā Sūtra, Supreme Golden Light Sūtra, and the Lion’s Roar of Queen Śrimālā Sūtra.

- 4. THE FOURTH PERIOD: THE WISDOM TEACHINGS

- This period lasted twenty-two years. Here Śākyamuni expounded the Perfection of Wisdom and its doctrines. According to the Perfection of Wisdom teaching, there is no way to awakening other than Mahāyāna teaching, which is based on the concept of emptiness.

- 5. THE FIFTH PERIOD: THE LOTUS AND NIRVANA SUTRAS

- This period comprises the last eight years of Śākyamuni’s teaching. He taught the Lotus Sūtra for eight years, followed by the Nirvāṇa Sūtra. There are varying ideas of how long the Nirvāṇa Sūtra was preached. According to the Preaching Travels Sūtra and the Hinayāna Nirvāṇa Sūtra it was three months just before Śākyamuni’s passing. Based on the contents of the Mahāyāna Nirvāṇa Sūtra it was one day and one night.

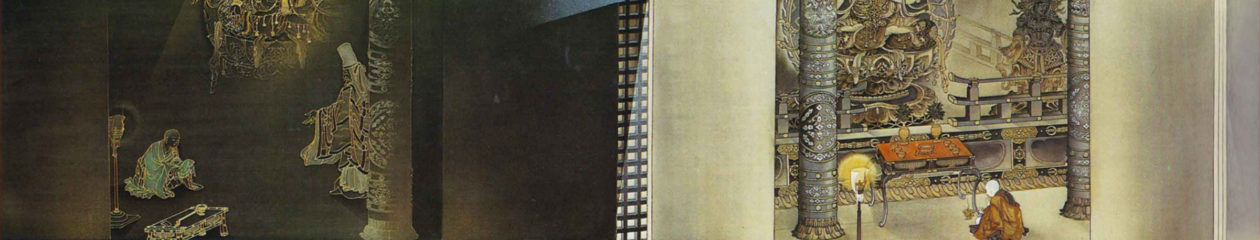

Grand Master Tiāntái’s life

History and Teachings of Nichiren Buddhism, p 99-100The following brief account of Grand Master Tiāntái’s life comes from Another Biography of the Great Master Zhizhe at Mount Tiāntái Guoqingsi. Great Master Tiāntái was given the posthumous name of Zhiyi. His parents named him Dean, with the family name of Chen. His father’s name was Chen Qizu, and his mother came from the Xu family. He lost his parents when he was seventeen years old, during the turbulent end of the Liang Dynasty. Soon after, he entered the Buddhist monastic life under Fazu at Guoyuansi temple and was awarded the complete monastic precepts from Precept Master Huikuang (543-613 CE). In 560 CE, Zhiyi visited Huisi (515-589 CE) on Mount Dasu, and under him studied the Lotus Sūtra. As a result of intense practice, he was said to have attained awakening through this phrase of the “Medicine King Chapter” of the Lotus Sūtra: “The Buddhas of those worlds praised him, saying simultaneously, ‘Excellent, excellent, good man! All you did was a true endeavor. You made an offering to us according to the true Dharma.’ ” Huisi certified his awakening.

With the recommendation of Huisi, Zhiyi left Mount Dasu, went to Jinling and stayed at Waguansi temple where he lectured to both clergy and laity over a period of eight years on the Title of the Lotus Sūtra, the Treatise on the Great Perfection of Wisdom, and the Source of the Meditation Gate. However, because of an anti-Buddhist movement by the Northern Zhou dynasty, Zhiyi retired to Mount Tiāntái in 575 CE at the age of 39. He undertook dhūta practice at the Flower Peak of the mountain, and lectured at Xiuchansi Temple. In 585 CE, at the age of 48, Zhiyi returned to Jinling, the capital of the Chen dynasty, at the request of the last emperor and governors of that dynasty.

In 587 CE, he gave lectures on the Lotus Sūtra, which were later compiled as The Words and Phrases of the Lotus Sūtra. To avoid the bloodshed caused by the conquest of the Chen dynasty by the Sui dynasty, Zhiyi stayed at Mount Lu and in the town of Changsha. In 591 CE, Prince Guang, later known as Yangdi, invited him to Yangzhou. He granted bodhisattva precepts to the prince, who gave him the honorific name Zhizhe.

Zhiyi established Yuquansi Temple in Jingzhou. He expounded The Profound Meaning of the Lotus Sūtra in 593 CE and The Great Calming and Contemplation in 594 CE. He returned to Mount Tiāntái in 595 CE. Two years later, in 597 CE, while he was on the way to see Prince Guang, he became sick and died at the age of 60.

The Importance of Grand Master Tiāntái Zhiyi

History and Teachings of Nichiren Buddhism, p 99Grand Master Tiāntái Zhiyi (538-597 CE) categorized Buddhist teachings according to the “two gates of doctrine and contemplation.” This categorization was based on the Lotus Sūtra and came to be known as the Tiāntái doctrine. Grand Master Jingxi Zhanran (711-782 CE), also known as Miaole, and Grand Master Dengyō Saichō (767-822 CE) later expanded these general categories.

Nichiren Shōnin criticized the teachings of Japanese Tendai Buddhism, and established his new doctrine, giving greater emphasis to faith, as building on the original Tiāntái doctrines. Hence, Nichiren Shū has always regarded the three major works written by Grand Master Tiāntái as important. It treats A Guide to the Tiāntái Fourfold Teaching of Chegwan (618-906 CE) as a basic study text.

Proper Buddhist Scriptures

History and Teachings of Nichiren Buddhism, p 96-98If proper Buddhist sūtras are regarded as only those taught by the historical Śākyamuni Buddha, the Lotus Sūtra cannot be regarded as a proper Buddhist sūtra. We could also suppose that Śākyamuni Buddha’s teachings had been handed down orally and as a result these were compiled into the Lotus Sūtra after Śākyamuni Buddha’s death. However, we cannot say that every word, every phrase and every story of the Lotus Sūtra are Śākyamuni Buddha’s teachings. These are too fictional to be Śākyamuni Buddha’s teachings.

Of course, the stage set in the Lotus Sūtra is that Śākyamuni Buddha achieved awakening forty-odd years before as explained in Chapter 15, and the Lotus Sūtra was taught directly by Śākyamuni Buddha himself. That is because, more than anything, the creators of the Lotus Sūtra had absolute confidence that they were following the original will of Śākyamuni Buddha, and in that sense, we can certainly think of the Lotus Sūtra as “the teaching of the Buddha.”

What then is the original will of the Buddha? “All living beings can become buddhas. There is no living being who cannot become a buddha.” Since they understood that this was the will of Śākyamuni Buddha, the creators of the Lotus Sūtra probably felt that a great gap had developed between the original will of the Buddha, the teachings of Nikāya Buddhism, and those of Mahāyāna Buddhism besides the Lotus Sūtra. Nikāya Buddhism does not recognize that we can achieve buddhahood, and Mahāyāna Buddhism besides the Lotus Sūtra does not admit that the pratyekabuddhas and śrāvakas could ever become buddhas. Under these circumstances, to revive the original will of Śākyamuni Buddha, the creators of the sutra put his purpose into a beautifully adorned narrative form and called it the Lotus Sūtra.

Of course, when the sūtra was written, it met with criticism. Chapter 13, “Encouragement for Keeping This Sūtra,” describes:

“They made that sutra by themselves

In order to deceive the people of the world.”These words may be the very words that the creators of the Lotus Sūtra were criticized with. From the same chapter:

“They will despise us,

Saying to us ironically,

‘You are Buddhas.’

But we will endure all these despising words.”Undoubtedly, they were showered with words of contempt such as, “How splendid your opinion is. Now you get to become buddhas.” Surely there were those who were not ready to accept the idea that “all people can become buddhas, even me and you.”

This kind of criticism is also reflected in Chapter 20, “Never-Despising Bodhisattva.” This bodhisattva stood in a town, bowed to people and said to them, “I respect you deeply. I do not despise you. Why is that? It is because you will be able to practice the Way of Bodhisattvas and become Buddhas.”

In response to his continuous message, he was neither praised nor encouraged. People struck him with sticks, wood, tile and stones, abusing him. As a pilgrim trying to spread the message of the Buddha that “All people can become buddhas. There is not a single person who cannot become a Buddha,” he encountered the ill will and at times even violence of people who said things like, “What gives you the right to say that?! You’re not the Buddha. You’re way out of line telling us we can become buddhas!”

However, despite the criticism, the creators and promoters of the Lotus Sūtra did not flag in their attempts. Due to their efforts, the basic will of Śākyamuni Buddha has been revived. Through their hands, Śākyamuni Buddha continues to live on, and continues to actively try to save others. Their confidence in this belief has supported those who expound the Lotus Sūtra over the years.

The Specific Transmission and the General Transmission

History and Teachings of Nichiren Buddhism, p 94Nichiren Buddhism considers Chapter 21 as specifically transmitting the spreading of daimoku in the Latter Age of the Degeneration of the Dharma to the bodhisattvas from underground represented by Superior Practice Bodhisattva. Then in Chapter 22, “Transmission,” the Buddha charges all the members of the assembly with spreading the Lotus Sūtra and all other sūtras in the buddhaless world. The former is called the “specific transmission,” the latter the “general transmission.” A deep analysis of these academic distinctions is not necessary. To answer the message of the Lotus Sūtra, we should think of this transmission as coming directly to us. Receiving this transmission, we must ourselves commit to becoming teachers of the Dharma and messengers of the Tathāgata and put this transmission into action.

Fostering Our Tie in This Life with the Lotus Sūtra.

History and Teachings of Nichiren Buddhism, p 94According to the Lotus Sūtra, Śākyamuni Buddha has continued since the infinite past to help us and lead us to salvation. Nonetheless, we are reborn as humans, still unable to achieve buddhahood. This means that we are deluded beings who in a past life turned our backs on the Buddha, deviated from the teachings of the Lotus Sūtra, and therefore have been unable to continue on the path to buddhahood. If we are to be messengers of the Tathāgata, we must not look away from our delusions. Rather, aware of our delusions, we must carefully foster our tie in this life with the Lotus Sūtra.