Six Perfections: Buddhism & the Cultivation of Character, p 33If, engulfed in our own world of concerns, we do not even notice when someone near us needs help, we will not be able to practice generosity. Similarly, if we maintain a distant posture toward others that, in effect, prevents them from appealing to us for help, we will rarely find ourselves in a position to give. The first skill that is vital to an effective practice of generosity is receptivity, a sensitive openness to others that enables both our noting their need and our receptivity to their requests. Our physical and psychological presence sets this stage and communicates clearly the kind of relation to others that we maintain.

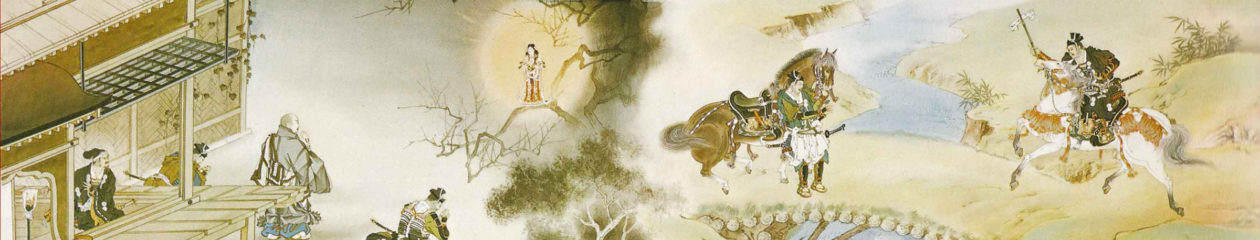

The traditional Mahayana image of perfection in the capacity for receptivity is the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (Guanyin), whose multiple arms are always extended in the gesture of generous outreach. The bodhisattva of compassion welcomes and invites all pleas for help. Other familiar forms of presence, other gestures, restrict the field of asking and giving; they are more or less closed rather than open to others. Arms folded tightly around ourselves communicate that we are self-contained, not open outwardly; arms raised in gestures of anger say even more about our relations to others. The extent to which we are sensitively open to others and the way in which we communicate that openness determine to a great extent what level of generosity we will be able to manifest. In sensitivity we open our minds to the very possibility that someone may need our assistance, and welcome their gestures toward us. Skillful generosity is attentive to these two basic conditions.