The practices carried out by the Buddha throughout his countless lifetimes (causes) and the resulting virtues of his enlightenment (effects) are contained in the daimoku and spontaneously accessed by the practitioner in the act of chanting. We can see this idea developing in a personal letter that Nichiren wrote the year before the Kanjin honzon shō:

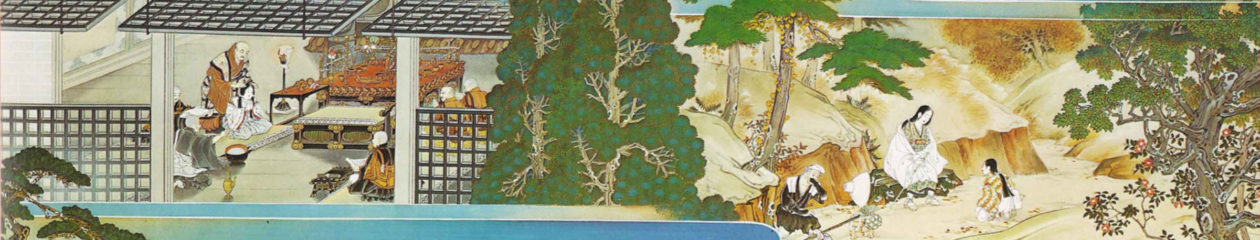

This jewel of [the character] myō contains the merit of the Tathāgata Śākyamuni’s Pāramitā of giving (danbaramitsu), when in the past he fed his body to a starving tigress or [gave his life] to ransom a dove; the merit of his Pāramitā of keeping precepts, when, as King Śrutasoma, he would not tell a lie; the merit gained as the ascetic Forbearance, when he entrusted his person to King Kali; the merit gained when he was Prince Donor, the ascetic Shōjari, [etc.] He placed the merit of all his six perfections (rokudo) within the character myō. Thus, even though we persons of the evil, last age have not cultivated a single good, he confers upon us the merit of perfectly fulfilling the countless practices of the six perfections. This is the meaning [of the passage], “Now this threefold world / is all my domain. / The beings in it / are all my children.” We ordinary worldlings, fettered [by defilements], at once have merit equal to that of Śākyamuni, master of teachings, for we receive the entirety of his merit. The sūtra states, “[At the start I made a vow / to make all living beings] / equal to me, without any difference.” This passage means that those who take faith in the Lotus Sūtra are equal to Śākyamuni Commoners [i.e., the heirs chosen to succeed the emperors Yao and Shun] immediately achieved royal status. Just as commoners became kings in their present body, so ordinary worldlings can immediately become Buddhas. This is what is meant by the heart of [the doctrine of] three thousand realms in one thought-moment.

Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism