This is another in a series of daily articles concerning Kishio Satomi's book, "Japanese Civilization; Its Significance and Realization; Nichirenism and the Japanese National Principles," which details the foundations of Chigaku Tanaka's interpretation of Nichiren Buddhism and Japan's role in the early 20th century.

In Satomi’s Nichirenism the “Holy Altar” is not only the key to the enlightenment of the country, but of the world.

Nichirenism and the Japanese National Principles, p111-112[Nichiren] beheld the signification of the relation between the Hokekyo and Nichiren himself through the fact of the wonderful combination of Japan. According to him, the world must be united as bretheren, namely as a moral world, and in the future the Holy Altar of the Hokekyo, especially the Honmon centric commandment, shall be established in Japan. He says in one of his significant essays, “On the Three Great Secret Laws” (San dai Hihō Shō):

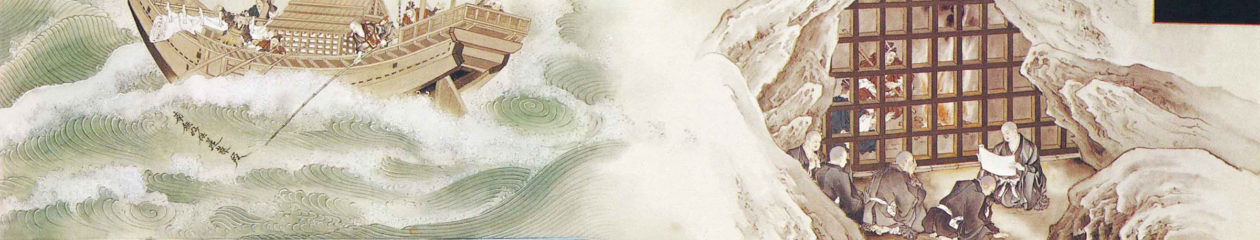

“At a certain future time, when the state law will unite with the Buddhist law and the Buddhist law harmonizes with the state law, and both sovereign and subjects will keep sincerely the Three Secret Laws, then will be realized such a golden age in the degeneration of the Latter Law, as it was in olden times under the rule of King Utoku. Thus the Holy Altar will be established with Imperial Sanction or the like at a place like the excellent paradise of Vulture Peak. We must only prepare and await the advent of the time. There is no other law or commandment which is practicable, only this one. This Holy Altar is not only the sanctuary for all nations of three countries (India, China and Japan) and the whole world, but even the great deities, Brahma and Indra, have to descend in order to initiate into the perfect truth of the Hokekyo ” (Works, pp. 240-41).

Western ideas about separating matters of religion from affairs of government are foreign to Nichiren’s thinking, according to Satomi.

Nichirenism and the Japanese National Principles, p102-103In the religious sense, the unification of the world or the salvation of the world is impossible unless the religion and the country assimilate. Nichiren, there fore, determined the country as the unit of salvation of the world as far as method is concerned. He says:

“Hearken! the country will prosper with the moral law, and the law is precious when practiced by man. If the country be ruined and human beings collapse, who would worship the Buddha, who would believe the law? First of all, therefore, pray for the security of the country and afterwards establish the Buddhist Law” (Works, p. 13).

This is a paragraph in his important essay, “Rissho Ankoku-ron” or “An Essay on the Establishment of Righteousness and Security of the Country.” He discoursed on the relation between the country and religion in this essay and sent it to the Hojos Government at an early date as an intimation of his religious movement; but this thought fully developed by degrees and eventually the doctrine of the Holy Altar was founded. There is no doubt that Nichiren thus thought of the country as the most concrete basis on which to propagate religion.

For Satomi’s Nichirenism, religion is necessary in all aspects of material life.

Nichirenism and the Japanese National Principles, p104Religion is intended to redeem living beings and their environment. Therefore, religion must purify the whole concrete life of man in order to religionize all individuals and the world. If religion does not in any sense concern material life, but merely spiritual life, then is religious influence almost in vain. A belief which purposely eliminates material affairs from the religious field is not only a misunderstanding of the essential meaning of religion, but is a very wrong view of human life. The true religious Empire can be established in the material world which is purified with spiritual signification. Nichiren’s doctrine of the Holy Altar is, indeed, an enlightenment of religion with material purification.

Satomi explains that the faithful must reconstruct the country so that it may exist “hand in hand with righteousness.”

According to Nichiren, in the degenerate days of the Latter Law, there is no Buddhist commandment outside of our vow for the reconstruction of the country and the realization of the Heavenly Paradise in the world. Even the so-called virtuous sage, if he does not embrace this great and strong vow, in other words only enjoys virtue individually, such a sage is pretty useless.

Although a man be imperfect, let him carry out Buddha’s task with the strong vow for the realization of Buddha’s Kingdom, with preaching or with economical power or with knowledge of sciences and with all sorts of such things. We can find the true significance of religion, of commandment, of human life therein.

Nichirenism and the Japanese National Principles, p105

Table of ContentsNext