It is difficult

To hear and receive this sūtra,

And ask the meanings of it

After my extinction.

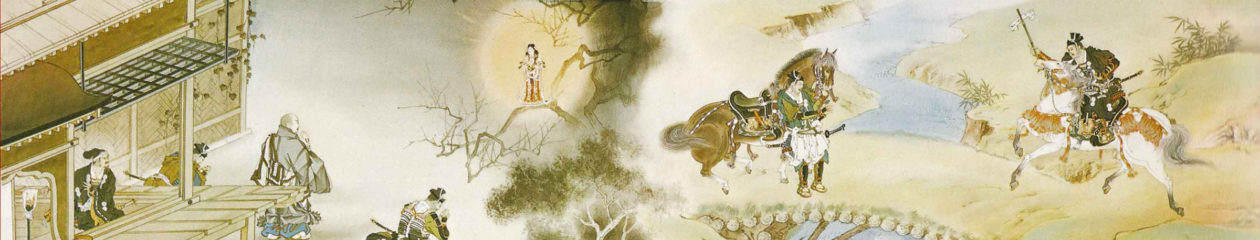

Chapter 11, Beholding the Stūpa of Treasures

In my more than 70 times reading the Lotus Sutra I’ve developed a firm faith that the sutra says what it means and means what it says. It was my pursuit of deepening my understanding that prompted me to enroll in Rissho Kosei-kai in North America’s (RKINA) advanced course on the Threefold Lotus Sutra.

I was attracted to this course because it promised a chapter-by-chapter review of the entire Threefold Lotus Sutra. I suppose it was my own naïveté that inspired me: I was looking for validation of my interpretation. I had failed to appreciate that the “advanced” course that Rissho Kosei-kai in North America offered was simply a retelling of founder Nikkyo Niwano’s interpretation of the Lotus Sutra as detailed in Buddhism for Today.

It was not until after last night’s discussion of Chapter 11, Beholding the Stūpa of Treasures, that I realized I had failed to understand that Rissho Kosei-kai has a very specific interpretation of what the Lotus Sutra says, and that this is one way in which Rissho Kosei-kai separates itself from Nichiren Shu and other Nichiren sects.

For Rissho Kosei-kai, Chapter 11, which Nikkyo Niwano titles, Beholding the Precious Stupa, takes on the roll of an essential lesson necessary to understand the meaning of Chapter 16, The Duration of the Life of the Tathāgata.

Here’s how Nikkyo Niwano summarizes the chapter in Buddhism for Today:

Buddhism for Today, p147-148First, we must explain the description of the Stupa of the Precious Seven springing from the earth. This Stupa symbolizes the buddha-nature that all people possess. Buddha-nature (the stupa) springing from the earth implies unexpectedly discovering one’s buddha-nature in oneself (the earth), which one had been predisposed to regard as impure. Hence the title of this chapter, “Beholding the Precious Stupa.”

In this Stupa is the Tathāgata Abundant Treasures, who symbolizes the absolute truth that was realized by the Tathāgata Śākyamuni. This truth never changes, and it has existed throughout the universe forever. The truth is revealed in the form of the various teachings of the Buddha, and it guides people everywhere. This is symbolized by the buddhas who have emanated from the Buddha and who are preaching the Law in worlds in all directions.

When the Tathāgata Abundant Treasures within the Precious Stupa shares half his throne with Śākyamuni Buddha, saying, “Śākyamuni Buddha! Take this seat!” Abundant Treasures testifies that all the teachings of the Tathāgata Śākyamuni are true. This testimony is delivered by truth itself. It may be difficult to understand the idea of the truth itself testifying to the truth, but in brief, this means that all that Śākyamuni Buddha has said is sure to come true eventually. To come true eventually is to testify that what the Buddha said is the truth. There can be no testimony more definite than this.

There is a deep meaning in the image of the Tathāgata Abundant Treasures as the truth and the Tathāgata Śākyamuni as its preacher sitting side by side cross-legged on the lion throne in the Stupa of the Precious Seven. This symbolizes the fact that were it not for a person who preaches the truth, ordinary people could not realize it, and that a preacher of the truth is as much to be honored as the truth itself.

Lastly, the great assembly reflected thus: “The Buddhas are sitting aloft and far away. Would that the Tathāgata by his transcendent powers might cause us together to take up our abode in the sky.” Then immediately Śākyamuni Buddha, by his transcendent powers, transferred the great assembly to the sky. This signifies that if people discover their buddha-nature in themselves, they will be able immediately to make their abode in the world of the buddhas.

This was not what I felt the chapter was saying, but, as the instructor in the class stressed last night, what’s actually said in the sutra isn’t necessarily what’s meant. Nikkyo Niwano prefaced his summary of Chapter 11, saying:

Buddhism for Today, p147As already explained in the Introduction, the Lotus Sutra often represents abstract ideas in the form of concrete images in order to help people grasp them. This entire chapter is a case in point.

And he underscored this at the conclusion of his summary:

Buddhism for Today, p148In this chapter, grasping the meaning of the text as a whole is more important than understanding the meaning of specific verses or words.

I see peril in this. First, it is unnecessary. The concept of a hidden Buddha nature was made explicit back in Chapter 8, The Assurance of Future Buddhahood of the Five Hundred Disciples, with the Parable of the Priceless Gem. And by completely eschewing the reason why the stupa suddenly appears, this interpretation robs the chapter of its literal meaning. As Śākyamuni explains in Chapter 11:

When [Many Treasures Buddha] was yet practicing the Way of Bodhisattvas, he made a great vow: “If anyone expounds a sūtra called the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma in any of the worlds of the ten quarters after I become a Buddha and pass away, I will cause my stūpa-mausoleum to spring up before him so that I may be able to prove the truthfulness of the sūtra and say ‘excellent’ in praise of him because I wish to hear that sūtra [directly from him].”

This vow offers an important assurance on the value of the Lotus Sutra. As Nichiren observed:

[A] character of the Lotus Sutra is as valuable as two characters because it was attested by the two Buddhas, Śākyamuni and [Many Treasures]; it is as precious as numerous characters because it was verified by numerous Buddhas all over the universe.

As I continue to study the Lotus Sutra and sift through the perspective of Rissho Kosei-kai, I’m left to my own devices.

As Nichiren wrote repeatedly, “True practicers of Buddhism should not rely on what people say, but solely on the golden words of the Buddha.”

Surely, studying the Lotus Sutra in this Sahā World qualifies as one of the difficult acts enumerated by Śākyamuni while seated next to Many Treasures Buddha in the Stupa of Treasures .