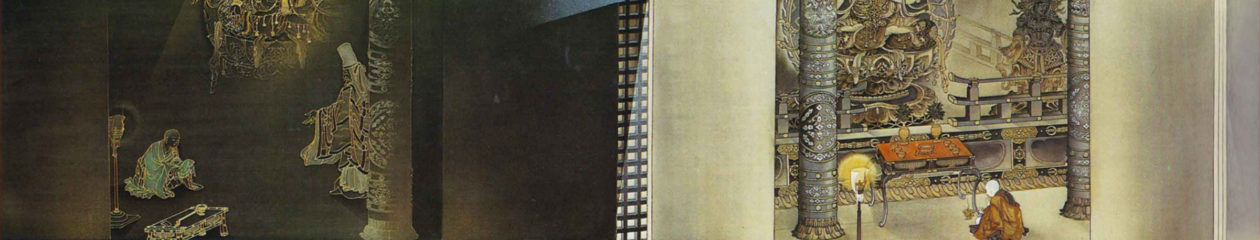

Two Buddhas, p208-209Nichiren took Sadāparibhūta [Never-Despising Bodhisattva] as a personal model and strongly identified with him. First, there were obvious parallels in their practice. “Sadāparibhūta was a practitioner at the initial stage of rejoicing,” Nichiren wrote, “while I am an ordinary person at the level of verbal identity. He sowed the seeds of buddhahood with twenty-four characters, while I do so with just five characters [Myō-hō-ren-ge-kyō]. The age differs, but the buddhahood realized is exactly the same.” This passage suggests that Nichiren saw Sadāparibhūta, like himself, as someone at the initial stages of practice who was carrying out shakubuku, planting the seeds of buddhahood in the minds of people who had never before received them. He saw other similarities as well. Both Nichiren and Sadāparibhūta lived long after the passing of the respective buddhas of their age, in an era of decline when there was much hostility. And both persevered in the face of emnity, enabling their persecutors to form a “reverse connection” (J. gyakuen) with the Lotus Sūtra. In short, Sadāparibhūta was for Nichiren an exemplar of practice for the latter age, and in this sense, he wrote, “The heart of the practice of the Lotus Sūtra is found in the ‘Sadāparibhūta’ chapter.”

Category Archives: 2buddhas

In Chanting the Daimoku All Have Full Access to Merits of Buddhahood

Two Buddhas, p198Nichiren’s assertion that, for Lotus practitioners of the mappō era, the daimoku replaces cultivation of the traditional three disciplines in effect opened the merits of the sūtra to persons without learning or insight. Here he used the analogies of a patient who is cured by medicine without understanding its properties, or of plants that, without awareness, bloom when they receive rainfall. In like manner, he said, beginning practitioners may not understand the meaning of the daimoku, but by chanting it, “they will naturally accord with the sūtra’s intent.” In making such claims, Nichiren was not taking an anti-intellectual stance that would deny the importance of Buddhist study. Nor was he negating the need for continuing effort in practice or the value of the qualities that the six perfections describe: generosity, self-discipline, forbearance, diligence, and so forth, even though he rejected the need to cultivate them formally as prerequisites for enlightenment. It is important to recall that Nichiren often framed his teaching in opposition to Pure Land teachers who insisted that the Lotus Sūtra should be set aside as too profound for ignorant persons of the Final Dharma age. As we have seen, this assertion appalled Nichiren, who saw it as blocking the sole path by which the people of this age could realize liberation. In response, he argued passionately that the Lotus Sūtra’s salvific scope embraces even the most ignorant persons; in chanting the daimoku, all have full access to the merits of buddhahood, without practicing over countless lifetimes or seeking liberation in a separate realm after death.

The Merits of the First Stage of Practice

Two Buddhas, p197-198[The] logic of total inclusivity underlies Nichiren’s explanation of the merits of the first stage of practice: rejoicing on hearing the Lotus Sūtra. “Since life does not extend beyond the moment,” he wrote, “the Buddha expounded the merits of a single moment of rejoicing [on hearing the Lotus Sūtra]. If two or three moments were required, this could no longer be called the original vow expressing his impartial great wisdom, the single vehicle of the sudden teaching that enables all beings to realize buddhahood.” In Nichiren’s reading, both the “first stage of faith” and the “first stage of practice” enumerated by Zhiyi on the basis of the “Description of Merits” chapter comprise “the treasure chest of the three thousand realms in a single thought-moment” and the gate from which all buddhas throughout time and space emerge.

Virtuous Attributes Contained Within The Daimoku

Two Buddhas, p197The “six perfections” systematize the practices required of Mahāyāna bodhisattvas to achieve buddhahood: giving, good conduct, perseverance, effort, meditation, and wisdom, in the Kubo and Yuyama translation. Traditionally, each perfection was said to require a hundred eons to complete, one eon being explained, for example, as the time required for a heavenly goddess to wear away great Mount Sumeru, the axis mundi, if she brushes it lightly with her sleeve once every hundred years. Such was the vast effort that Śākyamuni was said to have expended over staggering lengths of time in order to become the Buddha; the perfections represent his “causes” or “causal practices” and form the model for bodhisattva practice more generally. The wisdom, virtue, and power that he attained in consequence are his “resulting merits” or “effects.” Nichiren’s claim here is that all the practices and meritorious acts performed by Śākyamuni over countless lifetimes to become the Buddha, as well as the enlightenment and virtuous attributes he attained in consequence, are wholly contained within the daimoku and are spontaneously transferred to the practitioner in the act of chanting it.

The All-Encompassing Lotus Sutra

Two Buddhas, p196-197Nichiren grounded his reasoning in his understanding that the Lotus Sūtra, and specifically its title, is all-encompassing. In a famous passage, he explained that simply by upholding the daimoku, one can gain the merit of the entire bodhisattva path: “The Sūtra of Immeasurable Meanings states: ‘Even if one is not able to practice the six perfections, they will spontaneously be fulfilled.’ The Lotus Sūtra states, ‘They wish to hear the all-encompassing way. …’ The heart of these passages is that Śākyamuni’s causal practices and their resulting merits are inherent in the five characters myō-hō-ren-ge-kyō. When we embrace these five characters, he will spontaneously transfer to us the merits of his causes and effects.”

Manifesting the Buddha Land

Two Buddhas, p190-191A marginal, often persecuted figure with only a small following, Nichiren himself had to abandon expectations that this goal would be achieved soon. Nonetheless, he introduced into the tradition of Lotus Sūtra interpretation what might be called a millennial element, a prophecy or vision of an ideal world based on the spread of exclusive faith in the Lotus Sūtra. Especially since the modern period, that vision has undergone multiple reinterpretations from a range of social and political perspectives. Nichiren’s ideal of manifesting the buddha land in the present world gives his doctrine an explicitly social dimension that sets it apart from other Buddhist teachings of his day. It is also the aspect of his teaching that speaks most powerfully to the “this-worldly” orientation of today’s Buddhist modernism.

Transforming This World into an Ideal Buddha Realm

Two Buddhas, p190[F]or Nichiren, the immanence of the buddha land was not merely a truth to be realized subjectively, in the practice of individuals; it would actually become manifest in the outer world as faith in the Lotus Sūtra spread. We have already seen how he saw the disasters of his age as stemming fundamentally from rejection of the Lotus Sūtra in favor of inferior, provisional teachings no longer suited to the age. Conversely, he taught that — because people and their environments are inseparable — spreading faith in the Lotus Sūtra would transform this world into an ideal buddha realm. He famously argued this claim in his treatise Risshō anokoku ron, written early in his career, and maintained it throughout life. This was the conviction that underlay his aggressive proselytizing and that prompted him to risk his life in repeated confrontations with the authorities.

The Nonduality of Person and Land

Two Buddhas, p189-190The idea that the Buddha’s pure land is immanent in our deluded world by no means originated with Nichiren. The concept of the nonduality or inseparability of person and land, or of the living subject and their objective world (J. eshō funi), is integral to Zhiyi’s concept of three thousand realms in a single thought-moment. Because the environment mirrors the life condition of the persons inhabiting it, the world of hell dwellers would be hellish, while the world of a fully awakened person would be a buddha land. In light of the ichinen sanzen principle, to break through the narrow confines of the small self and to “see” or access the realm in which oneself (person) and everything else (environment) are mutually inclusive and inseparable is to realize enlightenment. As Zhanran expressed it, “You should know that one’s person and land are [both] the single thought-moment comprising three thousand realms. Therefore, when one attains the way, in accordance with this principle, one’s body and one’s mind in that moment pervade the dharma realm.” To manifest buddhahood is thus to experience this present world as the buddha land.

The Originally Enlightened Buddha of the Perfect Teaching Abides in This World

Two Buddhas, p189“The originally enlightened buddha of the perfect teaching abides in this world,” Nichiren wrote. “If one abandons this land, to what other land should one aspire? Wherever the practitioner of the Lotus Sūtra dwells should be considered the pure land.” Based on such thinking, Nichiren opposed the idea, extremely common in his time, of shunning this world as wicked and impure and aspiring to birth in the pure land of a buddha or bodhisattva after death. Because the various sūtras preached before the Lotus do not teach the perfect interpenetration of the buddha realm and the nine deluded realms, Nichiren asserted, the superior realms of buddhas and bodhisattvas that they mention, such as Amitābha’s Sukhāvati realm or Maitreya’s Tusita heaven, are merely provisional names; the “Lifespan” chapter of the Lotus reveals that the true pure land is to be realized here in the present, Sahā world.

The Joy of the Dharma

Two Buddhas, p189By devotion to the Lotus Sūtra and to its daimoku practice, Nichiren taught, one manifests the reality of ichinen sanzen — or more simply stated, the Buddha’s enlightened state — within oneself, opening a ground of experience that is joyful and meaningful, independent of whether one’s immediate circumstances are favorable or not. Nichiren called this the “joy of the dharma.” In the Lotus Sūtra’s language, even in a world “ravaged by fire and torn with anxiety and distress” one can, so to speak, experience the gardens, palaces, and heavenly music of the buddha realm.