Two Buddhas, p221Nichiren alludes to [the] direct transmission [of the Lotus Sūtra] in a personal letter connecting his retreat in the depths of Mount Minobu in Kai province, where he spent the last years of his life, to the “Transcendent Powers” chapter, where it says that wherever the Lotus Sūtra is practiced — “in a garden, a forest, under a tree, in a monk’s chamber, in a layman’s house, in a palace, on a mountain, in a valley, or in the wilderness” — is a sacred place of the Buddha’s activity. Nichiren elaborates: “This place is deep in the mountains, far from human habitation. East, west, north, or south, not a single village is to be found. Although I dwell in this forlorn retreat, hidden in the fleshly heart within my breast I hold the secret dharma of the ‘one great purpose’ transmitted from Śākyamuni Buddha, the lord of teachings, at Vulture Peak. Within my breast the buddhas enter nirvāṇa; on my tongue, they turn the wheel of the dharma; from my throat, they are born; and in my mouth, they attain supreme awakening. Because this the wondrous votary of the Lotus Sūtra dwells in this mountain, how could it be inferior to the pure land of Vulture Peak?”

Category Archives: 2buddhas

The Twofold Transmission

Two Buddhas, p220Nichiren’s idea of the transmission of the Lotus Sūtra is also twofold in another sense. On the one hand, the transmission unfolds through a line of teachers in historical time. Nichiren saw himself as heir to a lineage that passed from Śākyamuni Buddha, to Zhiyi, to Saichō, and then to himself — the “four teachers in three countries,” as he put it. The Nichiren tradition terms this the “outer transmission,” passing over the centuries from Śākyamuni Buddha down to Nichiren and his followers. At the same time, however, it speaks of an “inner transmission” received directly from the primordial buddha, namely, the daimoku itself. Nichiren said that teachers such as Zhiyi and Saichō had known inwardly of Namu Myōhō-renge-kyō but had not spoken of it openly because the time for its dissemination had not yet come.

General Transmission

Two Buddhas, p220[I]n Nichiren’s reading, in the “Transcendent Powers” chapter, the Buddha first transmitted the daimoku, Namu Myōhō-renge-kyō, to the bodhisattvas who had emerged from the earth, for them to propagate in the Final Dharma age. To presage this momentous event, the Buddha displayed his ten transcendent powers and, extracting the essence of the Lotus Sūtra, entrusted it to the four bodhisattvas. Then, in the “Entrustment” chapter, he made a more general transmission of the Lotus and all his other teachings to the bodhisattvas from other worlds, the bodhisattvas of the trace teaching who had been his followers in his provisional guise as the buddha who first attained awakening in this lifetime, and persons of the two vehicles. This general transmission was intended for the more limited period of the True Dharma and Semblance Dharma ages.

The Process of the Buddha’s Entrustment of the Lotus Sūtra

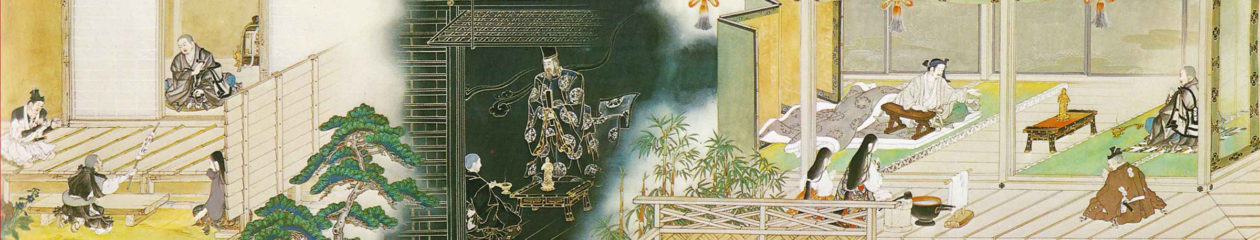

Two Buddhas, p218-220Let us review the process of the Buddha’s entrustment of the Lotus Sūtra from this twofold perspective. In the “Jeweled Stūpa” chapter, Śākyamuni Buddha calls for persons willing to spread the sūtra in an evil age after his nirvāṇa. Right before the concluding verse section, Śākyamuni announces: “The Tathāgata will enter parinirvāṇa before long and the Buddha wants to transmit this Lotus Sūtra to you.” Zhiyi says that this implies both a “near” transmission, to those bodhisattvas who have already assembled, and a “distant” transmission, to the bodhisattvas who will emerge from the earth several chapters later and to whom the Buddha will transfer the essence of the sūtra. In the “Perseverance” chapter, a great throng of bodhisattvas from other worlds vow to spread the Lotus Sūtra throughout the ten directions. But in the “Bodhisattvas Emerging from the Earth” chapter, Śākyamuni rejects their offer and instead summons his original disciples, the bodhisattvas from beneath the earth led by Viśiṣṭacaritra. Their appearance at the assembly in open space provides the occasion for Śākyamuni, in the “Lifespan” chapter, to cast off his provisional guise as someone who first realized enlightenment in the present lifetime and reveal his true identity as the primordially awakened buddha who “constantly resides” here in this world. Now in the “Transcendent Powers” chapter, he formally transfers the Lotus Sūtra to the bodhisattvas of the earth, who in the next chapter solemnly vow to uphold and disseminate it as the Buddha directs.

But what was transferred to the bodhisattvas of the earth? Śākyamuni declares that in the Lotus Sūtra he has “clearly revealed and taught all the teachings of the Tathāgata, all the transcendent powers of the Tathāgata, all the treasure houses of the hidden essence of the Tathāgata, and all the profound aspects of the Tathāgata.” Based on this passage, Zhiyi formulated five major principles of the Lotus Sūtra — its name, essence, purport, function, and position among all teachings — principles that he also understood as inherent in the five characters that comprise the sūtra’s title. Nichiren too spoke of “Namu Myōhō-renge-kyō endowed with the five profound principles,” drawing on the Tiantai commentarial tradition to assert that what Śākyamuni Buddha transferred to the bodhisattvas of the earth was none other than the daimoku, the heart or intent, of the Lotus Sūtra:

As for the five characters Myōhō-renge-kyō: Śākyamuni Buddha not only kept them secret during his first forty-some years of teaching, but also refrained from speaking of them even in the trace teaching, the first fourteen chapters of the Lotus Sūtra. Not until the “Lifespan” chapter did he reveal the two characters renge, which [represent the five characters and] indicate the original effect and original cause [of the Buddha’s enlightenment]. The Buddha did not entrust these five characters to Mañjuśrī, Samantabhadra, Maitreya, Bhaiṣajyarāja, or any other such bodhisattvas. Instead he summoned forth from the great earth of Tranquil Light the bodhisattvas Viśiṣṭacāritra, Anantacāritra, Vlśuddhacāritra, and Supratiṣṭhitacāritra along with their followers and transmitted the five characters to them.

Śākyamuni’s Transmission to the Future

Two Buddhas, p217-218Among Chinese exegetes, Zhiyi was the first to identify both Chapters 21 and 22 as describing Śākyamuni’s transmission to the future. Nichiren built upon Zhiyi’s reading to claim that there had been two transmissions: a specific transmission to Viśiṣṭacaritra and the other bodhisattvas who had emerged from beneath the earth, which occurs in the “Transcendent Powers” chapter, beginning from “Thereupon the Buddha addressed the great assembly of bodhisattvas, beginning with Viśiṣṭacaritra …”), and a general transmission, which occurs in the “Entrustment” chapter, to all the bodhisattvas, including those from other worlds and those instructed by Śākyamuni when he was still in his provisional guise as the historical Buddha, as he is represented in the trace teaching, as well as to persons of the two vehicles and others in the Lotus assembly.

Transcendent Powers of Nichiren’s Name

Two Buddhas, p216-217Nichiren’s name derives in part from his understanding of the “Transcendent Powers” chapter as foretelling that the bodhisattvas of the earth would appear at the beginning of the Final Dharma age. In premodern Japan, as in other cultures, it was common to change one’s name on entering a new stage of life or undergoing some transformative experience. Nichiren’s childhood name is said to have been Yakuō-maro. When he was first ordained, he assumed the monastic name Renchō. After reaching the insight that the daimoku of the Lotus Sūtra is the sole path of liberation in the Final Dharma age, he changed his name to Nichiren (“Sun Lotus”). The concluding verse section of [The Supernatural Powers of the Tathāgatas] chapter reads in part, “As the light of the sun and moon eliminates the darkness, these people practicing in the world will extinguish the blindness of sentient beings.” In the Chinese text, “these people,” the subject of this sentence, can be read either in the plural, as Kubo and Yuyama translate it, or in the singular, as Nichiren took it, that is, as referring to anyone – particularly himself, but also his followers – who took upon themselves the task of the Buddha’s original disciples to propagate the Lotus Sūtra in the Final Dharma age. As he comments:

Calling myself Nichiren (Sun Lotus) means that I awakened by myself to the buddha vehicle. That may sound as though I am boasting of my wisdom, but I say so for a reason. The sūtra reads, “As the light of the sun and moon eliminates the darkness. …” Think well about what this passage means. “These people practicing in the world” means that in the first five hundred years of the Final Dharma age, the bodhisattva Viśiṣṭacaritra will appear and illuminate the darkness of ignorance and defilements with the light of the five characters of Namu Myōhō-renge-kyō. As the bodhisattva Viśiṣṭacaritra’s envoy, I have urged all people of Japan to accept and uphold the Lotus Sūtra; that is what this passage refers to. The sūtra then goes on to say, “The wise … should preserve this sūtra after my nirvāṇa. Those people will be resolute and will unwaveringly follow the buddha path.” Those who become my disciples and lay followers should understand that we share a profound karmic relationship and spread the Lotus Sūtra as I do.

Forming a Reverse Connection

Noting that the all buddhas throughout time preach the Lotus Sūtra as the culmination of their teaching, Nichiren observed that the hostility encountered by Sadāparibhūta [Never-Despising Bodhisattva] in the age of a past buddha corresponded to the predictions of persecution made in Chapter Thirteen of the Lotus Sūtra as preached by the present buddha (Śākyamuni). One chapter tells of the past, the other foretells the future, but their content accords perfectly. When the Lotus Sūtra will be preached by buddhas in ages to come, he asserted, the present, “Perseverance,” chapter would become the “Sadāparibhūta” chapter of the future,” suggesting that its predictions would come true through his own actions, “and at that time I, Nichiren, will be its bodhisattva Sadāparibhūta.”

Based on his reading of these two chapters, Nichiren saw himself and his opponents as linked via the Lotus Sūtra in a vast soteriological drama of error, expiation, and the realization of buddhahood. Those who malign a practitioner of the Lotus Sūtra must undergo repeated rebirth in the Avici hell for countless eons. But because they have formed a “reverse connection” to the Lotus by slandering its votary, after expiating this error, they will eventually encounter the sūtra again and be able to become buddhas. By a similar logic, practitioners who suffer harassment must encounter this ordeal precisely because they maligned the Lotus Sūtra in the past, just as their tormenters do in the present. But because of those practitioners’ efforts to protect the Lotus by opposing slander of the dharma in the present, their own past offenses will be eradicated, and they will not only attain buddhahood themselves in the future, but also enable their persecutors to do the same. The Lotus practitioners and those who oppose them are thus inseparably connected through the sūtra in the same web of karmic causes that will ultimately lead both to buddhahood.

211-212

A Karmic Bond With Nichiren

Two Buddhas, p210-211In seeing himself as charged by the Buddha with the mission of disseminating the Lotus Sūtra in the evil, Final Dharma age, Nichiren identified with the noble and heroic figure of the bodhisattva Viśiṣṭacaritra, leader of the bodhisattvas of the earth. But at the same time, in seeing his trials as opportunities to rid himself of the consequences of past errors, he identified with the humbler figure of the bodhisattva Sadāparibhūta [Never-Despising Bodhisattva]. In so doing, Nichiren placed himself on the same level as the people he was attempting to save and identified a karmic bond between them.

Pounded in the Fire, Iron Is Forged into Swords

Two Buddhas, p210During the hardships of his exile to Sado Island, Nichiren became convinced that his own trials were not retributions for ordinary misdeeds. Rather, in previous lives, he himself must have slandered the dharma, the offense that he now so implacably opposed. He reflected: “From time without beginning I must have been born countless times as an evil ruler who robbed practitioners of the Lotus Sūtra of their clothing and food, paddies and fields … countless times I must have beheaded Lotus Sūtra practitioners.” Ordinarily, he explained, the karmic retribution for such horrific offenses would torment a person over the course of innumerable lifetimes. But by asserting the unique truth of the Lotus Sūtra and meeting persecution as a result, he had in effect summoned the consequences of those misdeeds into the present lifetime to be eradicated once and for all. “By being pounded in the fire, iron is forged into swords,” he said. “Worthies and sages are tested by abuse. My present sentence of exile is not because of even the slightest worldly wrongdoing. It has come about solely that I may expiate my past grave offenses in this lifetime and escape [rebirth in] the three evils paths in the next.”

Expiating His Past Errors

Two Buddhas, p209-210Nichiren … read the story of Sadāparibhūta [Never-Despising Bodhisattva] in a way that reflected — and perhaps inspired — his understanding of his own ordeals as a form of redemptive suffering. The prose portion of the “Sadāparibhūta” chapter says that those who mocked the bodhisattva suffered for a thousand eons in the Avici hell, but after expiating this offense, they were again able to meet him and were led by him to attain “the highest, complete enlightenment.” The verse section, however, suggests that the bodhisattva himself had “expiated his past errors” by patiently bearing the insults and mistreatment he received in the course of his practice. Nichiren focused on this second reading, encouraging his followers, and himself as well, by explaining that hardship encountered for the Lotus Sūtra’s sake would eradicate one’s past slanders against the dharma. “The bodhisattva Sadāparibhūta was not reviled and disparaged, and assailed with sticks and stones, for no reason,” Nichiren suggested. “It would appear that he had probably slandered the true dharma in the past. The phrase ‘having expiated his past errors’ seems to mean that because he met persecution, he was able to eradicate his sins from prior lifetimes.”