Two Buddhas, p164-165In Nichiren’s time, those who devoted themselves to reciting or copying the Lotus Sūtra as their primary practice were known as jikyōsha, “one who holds the sūtra.” Nichiren instead used the term gyōja (literally, “one who practices”; translated in this volume as “practitioner” or “votary”). Gyōja was often used to mean an adept or ascetic, denoting those who performed harsh austerities, such as going without sleep, fasting, and practicing in isolation in the mountains, with the aim of acquiring spiritual powers. Though Nichiren did not endorse ascetic practice for its own sake, his use of the word gyōja, like that of “bodily reading,” suggests both that he was “living” the Lotus Sūtra, personally encountering the hardships it predicts, and also that he had committed his life to its propagation. The term reflects his self-understanding as one entrusted with the task of spreading the Lotus in the Final Dharma age. He wrote, “None of the jikyōsha of Japan have encountered the trials predicted in these passages. I alone have read them. This is what is meant by the statement [in the “Perseverance” chapter], ‘We will not be attached to our bodies or lives. We only desire the highest path.’ This being the case, I am the foremost votary of the Lotus Sūtra in Japan.”

Category Archives: 2buddhas

Evil Persons Attaining Buddhahood

Two Buddhas, p 155-156According to conventional Buddhist thinking, moral conduct is the beginning and foundation of the path; persons can achieve liberation only by first renouncing evil and cultivating good. It is said that one cannot control one’s mind until one first learns to control one’s body and speech. The Buddhist ethical code seeks to provide such control. However, some Buddhist thinkers in Nichiren’s time were concerned with the problem posed by evils that one cannot avoid. This concern had to do with a keen awareness of human limitations, heightened by a sense of living in an age of decline. It also spoke to the situation of warriors, who were gaining influence both as a social group and as an emergent body of religious consumers. From a Buddhist perspective, warriors were trapped in a hereditary profession that was inherently sinful, requiring them to kill animals as a form of war training and kill humans on the battlefield. Thus, they could not escape violating the basic Buddhist precept against taking life. Nichiren, who had a number of samurai among his followers, stressed that, as long as one chants the daimoku, one will not be dragged down into the hells or other evil paths by ordinary misdeeds or unavoidable wrongdoing. To one warrior, a certain Hakii (or Hakiri) Saburō, he wrote: “In all the earlier sūtras of the Buddha’s lifetime, Devadatta was condemned as the foremost icchantika in all the world. But he encountered the Lotus Sūtra and received a prediction that he would become a tathāgata called Devarāja. … Whether or not evil persons of the last age can attain buddhahood does not depend upon whether their sins are light or heavy but rests solely upon whether or not they have faith in this sūtra.”

Opening of the Buddha Realm in the Act of Chanting the Daimoku

Two Buddhas, p145Nichiren understood the emergence of the jeweled stūpa as the opening of the buddha realm in the act of chanting the daimoku. One of his followers, a lay monk known as Abutsu-bō, once asked him what the jeweled stūpa signified. Nichiren explained that, in essence, the stūpa’s emergence meant that the śrāvaka disciples, on hearing the Lotus Sūtra, “beheld the jeweled stūpa of their own mind.” The same was true, he said, of his own followers: “In the Final Dharma age, there is no jeweled stūpa apart from the figures of those men and women who uphold the Lotus Sūtra. … The daimoku of the Lotus Sūtra is the jeweled stūpa, and the jeweled stūpa is Namu Myōhō-renge-kyō. … You, Abutsu-bō, are yourself the jeweled stūpa, and the jeweled stūpa is none other than you, Abutsu-bō. … So believing, chant Namu Myōhō-renge-kyō, and wherever you chant will be the place where the jeweled stūpa dwells.”

The Appearance of the Jeweled Stupa

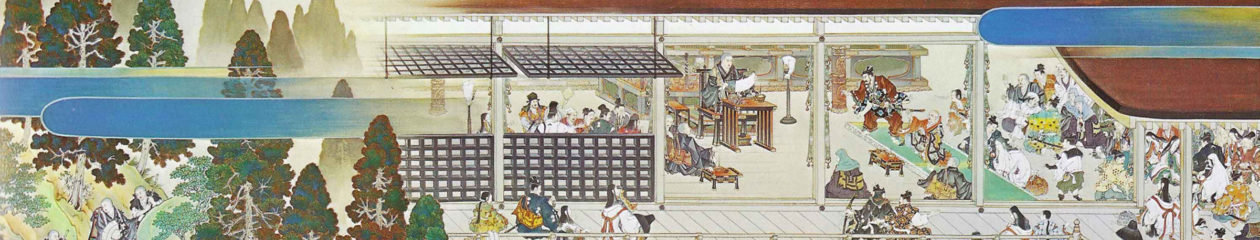

Two Buddhas, p 144Throughout East Asia, the imagery of [The Appearance of the Jeweled Stupa] chapter has inspired painting, sculpture, and exegesis. In Tiantai Buddhism, that imagery became part of a narrative of mythic origins: Zhiyi and his teacher Huisi, it was said, had together heard Śākyamuni Buddha’s original preaching of the Lotus Sūtra in the Vulture Peak assembly and were later born together in China, where they became master and disciple. The Japanese Tendai founder Saichō incorporated this tradition into his account of his Tendai dharma lineage. Shortly after Saichō’s death, when a new state-sponsored ordination platform was erected at the monastery that he had established on Mount Hiei, a representation of the jeweled stūpa of Prabhūtaratna, together with an image of Śākyamuni, was enshrined there. In medieval Japan, the Tendai esoteric “Lotus rite” or Hokke hō, conducted to realize buddhahood, eradicate sin, prolong life, quell disasters, and achieve other aims, employed a mandala depicting the two buddhas Śākyamuni and Prabhūtaratna, seated side by side on a lotus, in its central court.

Ānanda and the Lotus Sūtra

Two Buddhas, p123-124Ānanda receives a particularly marvelous prediction, with a very long lifespan and a very long duration of his teaching. This causes some of the bodhisattvas in the audience to be disgruntled, wondering why this monk who is not even an arhat received a better prophecy than they had. The Buddha explains that he and Ānanda had aroused the aspiration for perfect enlightenment in the presence of the same buddha long ago. Ānanda had wanted to preserve the dharma that Śākyamuni would eventually teach. For this reason, he receives this special prophecy. Upon hearing the prophecy, Ānanda is miraculously able to remember the teachings of innumerable buddhas of the past.

This elevation of Ānanda is yet another weapon used by the Lotus Sūtra to assert its legitimacy. If Ānanda can remember the teachings of innumerable buddhas of the past, he is certainly able to remember the teachings of Śākyamuni, suggesting that it was indeed Ānanda who says, “Thus have I heard” at the beginning of the sūtra. In the story of the first council in which he recited the sūtras, Ananda is taken to task by certain senior monks for having encouraged the Buddha to establish the order of nuns, a move that not all (male) members of the saṃgha had approved of. In the centuries that followed, Ānanda would become a beloved figure in the tradition, especially honored by nuns. That he receives a special prophecy in the Lotus Sūtra suggests that the authors of the text not only wished to bring him aboard the great ship of the Mahāyāna (as they did with Śāriputra), but perhaps also that they had a particular affection for him.

Buddhahood for All

Two Buddhas, p125The prophecies in these two chapters [Chapters 8 and 9], whether conferred on individuals or groups, each specify the name of the buddha whom the recipient will become, the name of his buddha land or field of activity, and the length of time that his teaching will endure. For the sūtra’s East Asian commentators, such concrete detail lent these predictions a level of credibility beyond any mere abstract assertion that “persons of the two other vehicles can become buddhas.” Because the Buddha knows the past, present, and future and never lies, it was certain that his śrāvaka disciples would in fact attain buddhahood just as he had predicted. For Nichiren, based on the premise that all ten realms are included in any one realm, the fact that śrāvakas can become buddhas meant that anyone else can as well. Thus, the Buddha’s prediction for any one of these figures could be read as a prediction of certain buddhahood for all who embrace the Lotus Sūtra, regardless of their status.

Our Karmic Connection to Śākyamuni Buddha

Two Buddhas, p116-117As with Chapter Three, Nichiren’s references to this chapter focus, not on the parable from which it takes its name, but on another element entirely, in this case, the story of the buddha Mahābhijfiājfiānābhibhū [Great-Universal-Wisdom-Excellence Tathāgata].

Nichiren drew three chief conclusions from this narrative. The first is that beings of our own, Sahā world have a karmic connection solely to Śākyamuni Buddha and not to the buddhas of other words. Everything about the dharma known in this world originated with Śākyamuni. None of the great Pure Land teachers, Nichiren said, had ever actually met the buddha Amitābha or renounced the world to practice the way under his guidance. The name Sahā, from the Sanskrit word meaning “to bear or endure,” refers to the tradition that this world is an especially evil and benighted place where it is difficult to pursue the Buddhist path — quite unlike the radiant pure lands with which the Mahāyāna imagination populated the cosmos. Thus, Śākyamuni was said to have displayed exceptional compassion in appearing in this world. In the Greater Amitābha Sūtra or Sūtra of Immeasurable Life, Amitābha Buddha vows to accept into his pure land all who place faith in him except those persons who have committed the five heinous deeds or disparaged the dharma. Nichiren accordingly suggested that these most depraved of evil persons had been excluded from the pure lands of the ten directions and were gathered instead in the present, Sahā world, where Śākyamuni had undertaken to save them. This was the meaning, he said, of Śākyamuni Buddha’s statement in Chapter Three, “I am the only one who can protect them.” To forsake the original teacher Śākyamuni was a grave error, as the people of this world cannot escape samsāra by following any other buddha.

Sowing, Maturing, and Harvesting

Two Buddhas, p117-118Nichiren drew from the Mahābhijfiājfiānābhibhū [Great-Universal-Wisdom-Excellence Tathāgata] story an understanding of how the Buddha’s pedagogical method unfolds over time. Zhiyi had identified three standards of comparison by which the Lotus Sūtra could be said to surpass all others. The first, based on Śākyamuni’s declaration of the one buddha vehicle in the “Skillful Means” and subsequent chapters, is that it encompasses persons of all capacities. The second, based on the present, “Apparitional City” chapter, is that it reveals the process of the Buddha’s instruction from beginning to end. Drawing on the Mahābhijfiājfiānābhibhū narrative, Zhiyi described this process with the metaphor of “sowing, maturing, and harvesting.” That is, the Buddha implants the seed of buddhahood in the mind of his disciples with an initial teaching; cultivates it through subsequent teachings, enabling their capacity to mature; and finally reaps the harvest by bringing those disciples to full enlightenment. As the opening passage of this chapter describes, the buddha Mahābhijfiājfiānābhibhū lived an immensely long time ago, so long that one could measure it only by grinding a vast number of world systems to dust and using each dust speck to represent one eon. In that distant time, Mahābhijfiājfiānābhibhū and his sixteen sons planted the seed of buddhahood in the minds of their auditors by preaching the Lotus Sūtra. Those who heard the Lotus Sūtra from the sixteenth son were born together with him in lifetime after lifetime, as he nurtured their capacity, bringing it to maturity with subsequent teachings over the course of innumerable lifetimes. When that son preached the Lotus Sūtra in the Sahā world as Śākyamuni Buddha, some were at last able to reap the harvest of enlightenment, while others would do so in the future. In other words, Śākyamuni’s resolve to lead all beings to the one vehicle was not merely a matter of this lifetime, but a project initiated in the inconceivably remote past. Indeed, this chapter offers another early hint that Śākyamuni’s buddhahood encompasses a time frame far exceeding the present lifetime, a theme that the Lotus Sūtra develops in later chapters.

Teaching Śrāvakas the Taste of Ghee

Two Buddhas, p106-107Nichiren explained that these four great śrāvakas “had not even heard the name of the delicacy called ghee,” but when the Lotus Sūtra was expounded, they experienced it for the first time, savoring it as much as they wished and “immediately satisfying the hunger that had long been in their hearts.” Nichiren’s reference here to “ghee,” or clarified butter, invokes the concept of the “five flavors,” an analogy by which Zhiyi had likened the stages in human religious development to the five stages in the Indian practice of making ghee from fresh milk. As we have seen, like other educated Buddhists of his day, Nichiren took the Tendai division of the Buddha’s teaching into five sequential periods to represent historical fact. From that perspective, Nichiren sometimes described the sufferings that he imagined the Buddha’s leading śrāvaka disciples must have endured during the period when Śākyamuni began to preach the Mahāyāna, seeing their status plummet from that of revered elders to targets of scorn and reproach for their attachment to the inferior “Hinayāna” goal of a personal nirvāṇa. Some Mahāyāna sūtras excoriate the śrāvakas as those who have “destroyed the seeds of buddhahood” or “fallen into the pit of nirvāṇa” and can benefit neither themselves nor others. Their “hunger” then would have represented their chagrin and regret at not having followed the bodhisattva path and thus having excluded themselves from the possibility of buddhahood.

At the same time, Nichiren imagined them suffering hunger in the literal sense. As monks, they would have had to beg for their food each day. Nichiren imagined that on hearing the érävakas rebuked as followers of a lesser vehicle, humans and gods no longer viewed them as worthy sources of merit and stopped putting food in their begging bowls. “Had the Buddha entered final nirvāṇa after preaching only the sūtras of the first forty years or so without expounding the Lotus Sūtra in his last eight years, who then would have made offerings to these elders?” he asked. “In their present bodies, they would have known the sufferings of the realm of hungry ghosts.” Serious hunger was a condition that Nichiren had experienced at multiple points in his life and with which he could readily sympathize. But when the Buddha preached the Lotus Sūtra and predicted buddhahood for the śrāvakas, Nichiren continued, his words were like the brilliant spring sun emerging to dissolve the ice of winter or a strong wind dispersing dew from all the grass. “Because [these predictions] appear in this phoenix of writings, this mirror of truth [i.e., the Lotus], after the Buddha’s passing, the śrāvakas were venerated by all supporters of the dharma, both humans and gods, just as though they had been buddhas.”

The Blessings of Faith in the Lotus Sūtra

Two Buddhas, p100-101The promise in this chapter that those who embrace the one vehicle will be “at peace in this world” and in the next, will be “born into a good existence” articulates what most people sought from religion in Nichiren’s day: good fortune and protection in their present existence and some sort of assurance of a happy afterlife. Traditionally, as with other religions, people expected from Buddhism not only wisdom and insight, but also practical benefits: healing, protection, and worldly success. Nichiren often cited this passage to assure followers that faith in the Lotus Sūtra does indeed offer such blessings. “Money changes form according to its use,” he wrote. “The Lotus Sūtra is also like this. It will become a lamp in the darkness or a boat at a crossing. It can become water; it can also become fire. This being so, the Lotus Sūtra guarantees that we will be ‘at peace in this world’ and be ‘born into a good existence in the future.’ “