Day 13 covers all of Chapter 8, The Assurance of Future Buddhahood of the Five Hundred Disciples.

Having last month considered the prediction for the twelve hundred Arhats, we consider the Parable of the Priceless Gem.Thereupon the five hundred Arhats, having been assured by the Buddha of their future Buddhahood, felt like dancing with joy, stood up from their seats, came to the Buddha, worshipped him at his feet with their heads, and reproached themselves for their faults, saying:

“World-Honored One! We thought that we had already attained perfect extinction. Now we know that we were like men of no wisdom because we were satisfied with the wisdom of the Lesser Vehicle although we had already been qualified to obtain the wisdom of the Tathāgata.

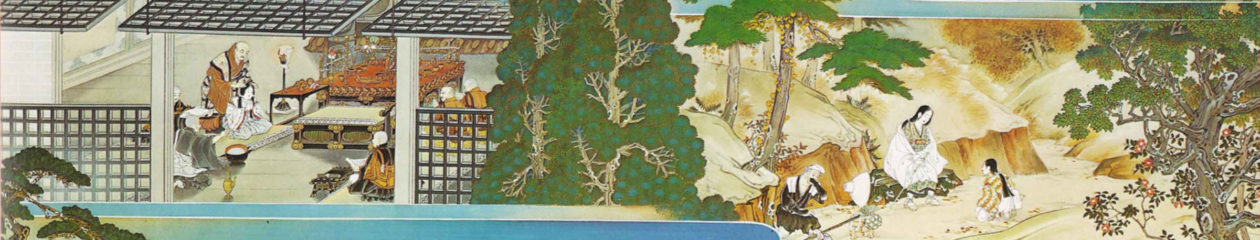

“World-Honored One! Suppose a man visited his good friend. He was treated to drink, and fell asleep drunk. His friend had to go out on official business. He fastened a priceless gem inside the garment of the man as a gift to him, and went out. The drunken man did not notice what his friend had given him. After a while he got up, and went to another country. He had great difficulty in getting food and clothing. He satisfied himself with what little he had earned. Some time later the good friend happened to see him. He said, ‘Alas, man! Why have you had such difficulty in getting food and clothing? T fastened a priceless gem inside your garment on a certain day of a certain month of a certain year so that you might live peacefully and satisfy your five desires. The gem is still there, and you do not notice it. You are working hard, and worrying about your livelihood. What a fool you are! Trade that gem for what you want! You will not be short of anything you want.’

“You, the Buddha, are like his friend. We thought that we had attained extinction when we attained Arhatship because we forgot that we had been taught to aspire for the knowledge of all things by you when you were a Bodhisattva just as the man who had difficulty in earning his livelihood satisfied himself with what little he had earned. You, the World-Honored One, saw that the aspiration for the knowledge of all things was still latent in our minds; therefore, you awakened us, saying, ‘Bhikṣus! What you had attained was not perfect extinction. I caused you to plant the good root of Buddhahood a long time ago. [You have forgotten this; therefore,] I expounded the teaching of Nirvāṇa as an expedient. You thought that you had attained true extinction when you attained the Nirvāṇa [ which I taught you as an expedient].’

“World-Honored One! Now we see that we are Bodhisattvas in reality, and that we are assured of our future attainment of Anuttara-samyak-saṃbodhi. Therefore, we have the greatest joy that we have ever had.”