Day 25 covers all of Chapter 20, Never-Despising Bodhisattva, and opens Chapter 21, The Supernatural Powers of the Tathāgatas.

Having last month concluded today’s portion of Chapter 21, The Supernatural Powers of the Tathāgatas, we return to Chapter 20 and meet Powerful-Voice-King Buddha.Thereupon the Buddha said to Great-Power-Obtainer Bodhisattva-mahāsattva:

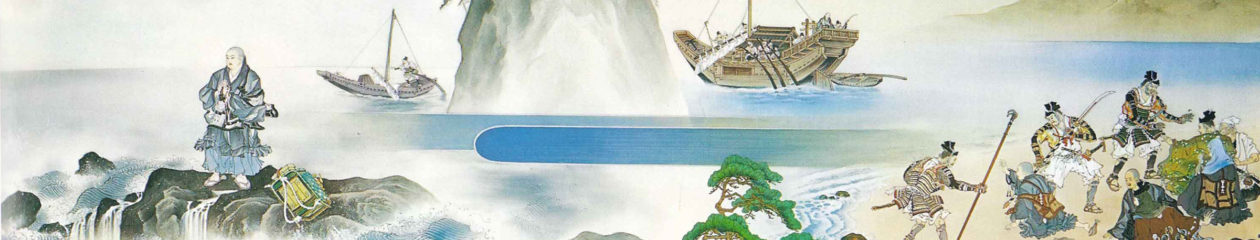

“Know this! Anyone who speaks ill of or abuses or slanders the bhikṣus, bhikṣunīs, upāsakās or upāsikās who keep the Sūtra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma, will incur the retributions previously stated. Anyone [who keeps this sūtra] will be able to have his eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body and mind purified, that is to say, to obtain the merits as stated in the previous chapter.“Great-Power-Obtainer! Innumerable, limitless, inconceivable, asaṃkhya kalpas ago, there lived a Buddha called Powerful-Voice-King, the Tathāgata, the Deserver of Offerings, the Perfectly Enlightened One, the Man of Wisdom and Practice, the Well-Gone, the Knower of the World, the Unsurpassed Man, the Controller of Men, the Teacher of Gods and Men, the Buddha, the World-Honored One. The kalpa in which he lived was called Free-From-Decay; and his world, Great-Achievement. Powerful-Voice-King Buddha expounded the Dharma to the gods, men and asuras of his world. To those who were seeking Śrāvakahood, he expounded the teaching suitable for them, that is, the teaching of the four truths, saved them from birth, old age, disease and death, and caused them to attain Nirvana. To those who were seeking Pratyekabuddhahood, he expounded the teaching suitable for them, that is, the teaching of the twelve causes. To the Bodhisattvas who were seeking Anuttara-samyak-saṃbodhi, he expounded the teaching suitable for them, that is, the teaching of the six paramitas, and caused them to obtain the wisdom of the Buddha.

“Great-Power-Obtainer! The duration of the life of Powerful-Voice-King Buddha was forty billion nayuta kalpas, that is, as many kalpas as there are sands in the River Ganges. His right teachings were preserved for as many kalpas as the particles of dust of the Jambudvipa. The counterfeit of his right teachings was preserved for as many kalpas as the particles of dust of the four continents. The Buddha benefited all living being and then passed away. After [the two ages:] the age of his right teaching and the age of their counterfeit, there appeared in that world another Buddha also called Powerful-Voice-King, the Tathāgata, the Deserver of Offerings, the Perfectly Enlightened One, the Man of Wisdom and Practice, the Well-Gone, the Knower of the World, the Unsurpassed Man, the Controller of Men, the Teacher of Gods and Men, the Buddha, the World-Honored One. After him, the Buddhas of the same name appeared one after another, two billion altogether.

The Introduction to the Lotus Sutra offers this on ages of the Buddha’s teachings:

The terms, “Age of Right Teachings” and “Age of Counterfeit Teachings,” express the Buddhist view of history. It is believed that for a while after a Buddha has entered Nirvana, people will remember his teachings correctly, put them into practice, and attain enlightenment. However, as time passes, those teachings will become mere academic formalities. People will know about them and be able to discuss them, but they will no longer practice them diligently and attain enlightenment. This second period is called the Age of Counterfeit Teachings. Finally, the teachings will decay altogether. People will neither practice them, understand them, nor attain enlightenment. This is the Age of Degeneration, when Buddhism declines and finally fades away. It is believed by most scholars that the first and second periods last for a thousand years each. The Age of Degeneration can drag on for as long as 10,000 years. In any case, Never-Despising Bodhisattva lived during the second of these three periods, an Age of Counterfeit Teachings.

Introduction to the Lotus Sutra