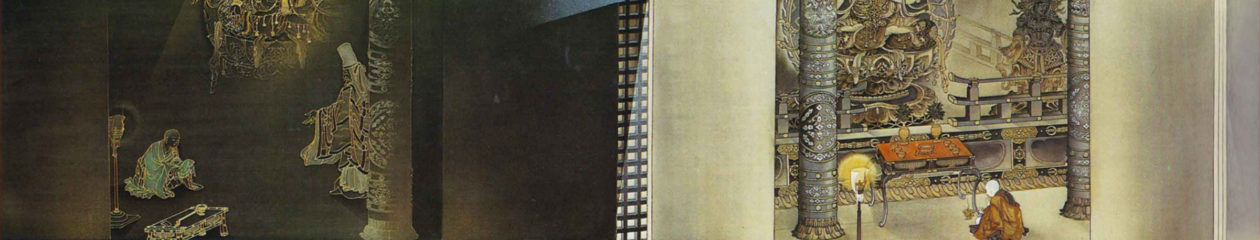

Two Buddhas, p227-228[T]he Lotus Sūtra seems to urge giving one’s life in its service. Bodhisattvas in the “Perseverance” chapter vow that they “will not be attached to our bodies or lives,” and the “Lifespan” chapter says that the primordial Śākyamuni Buddha will appear before those beings who “are willing to give unsparingly of their bodies and their lives.” How should such passages be understood?

Nichiren addresses this issue in a letter to a disciple, the lay nun Myōichi-ama, expressing sympathy on the death of her husband, who had held fast to his faith despite great difficulties: “Your late husband gave his life for the Lotus Sūtra. His small landholding that barely sustained him was confiscated on account of [his faith in] the Lotus Sūtra. Surely that equaled ‘giving his life.’ The youth of the Snow Mountains [described in the Nirvāṇa Sūtra] offered his body in exchange for half a verse [of a Buddhist teaching], and the bodhisattva Medicine King [Bhaiṣajyarāja] burned his arms [in offering to the Buddha]. They were saints, [and for them, such acts were] like water poured on fire. But your husband was an ordinary man, [and so for him, this sacrifice was] like paper placed in fire. When we take this into consideration, his merit must surely be the same as theirs.”

Monthly Archives: October 2019

Tricycle Talks to Two Authors

Two Buddhas Seated Side by Side authors Donald Lopez, Jr. and Jacqueline Stone sit down with Tricycle Editor and Publisher James Shaheen.

Two Stars for Two Buddhas Seated Side by Side

It didn’t take long for me to realize Two Buddhas Seated Side by Side wasn’t what I had expected. I wrote a Two Star review on Amazon:

Jacqueline I. Stone gets 5 stars for her contribution to this book. Donald S. Lopez Jr. gets a negative three. Stone is famous for her scholarly work on the Lotus Sutra and the 13th century monk Nichiren. Lopez has no appreciation for this sutra and consistently demonstrates his disdain for all Mahayana Buddhism. Stone’s contribution to this book, which seeks to marry her insight into how the Lotus Sutra was interpreted in medieval Japan with a chapter by chapter analysis of the sutra, just can’t survive Lopez’s poison.

Over the last several days I’ve been inputting the quotes from Stone’s portion of the book that I will use as part of my 32 Days of the Lotus Sutra practice. I should have enough material to fill three, maybe four, rotations, although as I progress fewer and fewer of the quotes will address that day’s reading.

Having finished the book, I’ve amended my Amazon review. It’s still two stars:

At the conclusion of the book, the authors say:

Our first aim in this volume was to introduce readers to the rich content of the Lotus Sūtra, one of the most influential and yet enigmatic of Buddhist texts, and to provide a basic chapter-by-chapter guide to its often-bewildering narrative. Our secondary aims were related to hermeneutics. Through the example of the Lotus Sūtra, and its reading by Nichiren, one of its most influential devotees, we have sought to illuminate the dynamics by which Buddhists, at significant historical moments, have reinterpreted their tradition. Thus, this study has taken a very different perspective from that of commentaries intended primarily to elucidate the Lotus Sūtra as an expression of the Buddhist truth or as a guide to Buddhist practice. Our intent is not to deny the sūtra’s claim to be the Buddha’s constantly abiding dharma; rather, we have been guided by the conviction that the full genius of the Lotus as a literary and philosophical text comes to light only when the sūtra is examined in terms of what can be known or even surmised about the circumstances of its compilation. Adopting that perspective suggests how the compilers may have grappled with questions new to their received tradition and how they refigured that tradition in attempting to answer them. (Page 263)

This first aim is reasonably accomplished but it is the secondary aim that is well wide of the target. Lopez is responsible for this and his claim that “Our intent is not to deny the sūtra’s claim to be the Buddha’s constantly abiding dharma” is undermined by denigration of all Mahayana teachings throughout the book, the most glaring example being his description of the Lotus Sutra on Page 56:

The Lotus Sūtra, like all Mahāyāna sūtras, is an apocryphal text, composed long after the Buddha’s death and yet retrospectively attributed to him.

Yes, I would have been happier if Lopez and Stone had chosen instead to write a book “intended primarily to elucidate the Lotus Sūtra as an expression of the Buddhist truth or as a guide to Buddhist practice.” But describing all Mahayana Buddhism as somehow outside Mainstream Buddhism does not illuminate how Buddhists over the years have dynamically reinterpreted their tradition.

Understanding the Perfect Precepts

The Fan wang precepts could not be understood as Perfect precepts until they had been interpreted according to the teachings of the Lotus Sūtra and the Tendai School. Such a view is not surprising since Saichō was defending the Lotus Sūtra in works such as the Shugo kokkaishō at the same time he was composing the Kenkairon. Saichō emphasized the role of the Lotus Sūtra by naming Śākyamuni Buddha the preceptor in the ordination ceremony and by asserting that the Ryōzen lineage was valid for the precepts. Five years after his death, Saichō’s disciples constructed a precepts platform with Śākyamuni and a Tahōtō (stūpa for Prabhūtaratna Tathāgata) occupying the central places on it.

The Fan wang Ching played the key role in the practice and interpretation of the Perfect precepts. However, the interpretation of the precepts was not complete until the Perfect sense of the Lotus Sūtra had been applied to them. This did not mean, however, that the Fan wang Ching could be ignored. Rather the Fan wang Ching specified the contents of the precepts. Saichō did not elaborate on the relative value of the two sūtras because he believed that the two texts contained Perfect teachings preached by Buddhas who were essentially the same. Elements from the Lotus Sūtra and its capping sūtra, the Kuan p’u hsien Ching, could be harmoniously combined with precepts from the Fan wang Ching because the Perfect purport of all three works was the same.

Saichō: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School, p212Universal Causation and the Moral Code It Implies

The Buddhist law of dependent origination teaches that everything in the universe is interrelated and that all human beings live in an organically structured world, all of whose parts are interdependent. To attempt to divorce oneself from the whole and seek no more than one’s own personal bliss is to ignore the principle of universal causation and the moral code it implies. This is why the Buddha rejected both meditation and asceticism as paths to enlightenment: both mistake a false cause for a true one.Basic Buddhist Concepts

Difficulties Depending on Sūtra Practiced

No matter which sūtra one practices, he who practices Buddhism is bound to encounter difficulties depending on the sūtra he practices. Of all sūtras, the practicer of the Lotus Sūtra is faced with the most severe obstacles, especially in the Latter Age of Degeneration, when it is stated in the sūtra that it is most suited to the time and the capacity of people. Therefore, Grand Master Miao-lê states in his Annotations on the Great Concentration and Insight, fascicle 8, “Seeing people not desirous of cutting the chain of life and death and not aspiring to the way leading to Buddhahood, the devil will cherish them as if he were their real parent.”

The meaning of this interpretation is that even though a person practices meritorious acts, if he practices only those teachings such as the nembutsu, Shingon, Zen and Ritsu without practicing the Lotus Sūtra, the true way leading to Buddhahood, the king of devils will act as though he were the practicer’s parent, and haunt many people to entertain and make offerings to the practicers. It is for the purpose of deceiving people into believing in him as a true practicer of Buddhism. It is like the priest who is respected by the king and therefore highly esteemed with offerings by ordinary people. The fact that the ruler of the country looks upon Nichiren as an enemy, on the contrary, proves that Nichiren is the practicer of the True Dharma.

Shuju Onfurumai Gosho, Reminiscences: from Tatsunokuchi to Minobu, Writings of Nichiren Shōnin, Biography and Disciples, Volume 5, Pages 33

Daily Dharma – Oct. 26, 2019

All of you, wise men!

Have no doubts about this!

Remove your doubts, have no more!

My words are true, not false.

The Buddha sings these verses in Chapter Sixteen of the Lotus Sūtra. If we come to the Buddha, attached to our delusions and fearful of the potential for peace and joy we all have within us, it is easy to doubt what he says. We have been suffering a long time. Like the children playing in the burning house, we are so caught up in the drama and insanity of our world that we cannot imagine any other way to live. When the Buddha warns us of how dangerous it is to continue as we are, we are more certain of our familiar pain than of his enlightenment. When we trust the Buddha Dharma, and cultivate our potential to create unimaginable benefit in this world, then we realize the pettiness of the crises we create for ourselves. We awaken our curiosity and gratitude and learn to see this beautiful world for what it is.

The Daily Dharma is produced by the Lexington Nichiren Buddhist Community. To subscribe to the daily emails, visit zenzaizenzai.com

Day 25

Day 25 covers all of Chapter 20, Never-Despising Bodhisattva, and opens Chapter 21, The Supernatural Powers of the Tathāgatas.

Having last month learned about a bhikṣu called Never-Despising, we consider what became of Never-Despising Bodhisattva.

“When he said this, people would strike him with a stick, a piece of wood, a piece of tile or a stone. He would run away to a distance, and say in a loud voice from afar, ‘I do not despise you. You will become Buddhas.’ Because he always said this, he was called Never-Despising by the arrogant bhikṣus, bhikṣunīs, upāsakās and upāsikās. When he was about to pass away, he heard [from a voice] in the sky the twenty thousand billion gāthās of the Sūtra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma, which had been expounded by the Powerful-Voice-King Buddha. Having kept all these gāthās, he was able to have his eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body and mind purified as previously stated. Having his six sense-organs purified, he was able to prolong his life for two hundred billion nayuta more years. He expounded this Sūtra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma to many people [in his prolonged life]. The arrogant bhikṣus, bhikṣunīs, upāsakās and upāsikās, that is, the four kinds of devotees who had abused him and caused him to be called Never-Despising, saw that he had obtained great supernatural powers, the power of eloquence, and the great power of good tranquility. Having seen all this, and having heard the Dharma from him, they took faith in him, and followed him.

“This Bodhisattva also taught thousands of billions of living beings, and led them into the Way to Anuttara-samyak-saṃbodhi. After the end of his prolonged life, he was able to meet two hundred thousand million Buddhas, all of them being called Sun-Moon-Light. He also expounded the Sūtra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma under them. After that, he was able to meet two hundred thousand million Buddhas, all of them being called Cloud-Freedom-Light-King. He also kept, read and recited this sūtra, and expounded it to the four kinds of devotees under those Buddhas so that he was able to have his natural eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body and mind purified and to become fearless in expounding the Dharma to the four kinds of devotees.

“Great-Power-Obtainer! This Never-Despising Bodhisattva-mahāsattva made offerings to those Buddhas, respected them, honored them, praised them, and planted the roots of good. After that, he was able to meet thousands of billions of Buddhas. He also expounded this sūtra under those Buddhas. By the merits he had accumulated in this way, he was able to become a Buddha.

Always Despised But Never Despising

Two Buddhas, p207We cannot know for certain, but the story of Sadāparibhūta [Never-Despising Bodhisattva] may reflect the experience of the Lotus Sūtra’s compilers in encountering anger and contempt from mainstream Buddhist monastics. The Sanskrit name Sadāparibhūta actually means “Always Despised.” As an ordinary monk without any particular accomplishments, Sadāparibhūta had no obvious authority for delivering predictions of future buddhahood, and monastics who looked askance at the nascent Mahāyāna movement may have found his words presumptuous and offensive. Hence, he was “always despised.” Dharmaraksa, who first rendered the Lotus Sūtra into Chinese, translated the bodhisattva’s name in this way. But Kumārajīva instead adopted “Never Despising,” shifting emphasis to the bodhisattva’s attitude of reverence for all. As Nichiren expresses it: “In the past, the bodhisattva Sadāparibhūta carried out the practice of veneration, saying that all beings have the buddha nature; that if they embrace the Lotus Sūtra, they are certain to attain buddhahood; and that to slight another is to slight the Buddha himself. He bowed even to those who did not embrace the Lotus Sūtra, because they too had the buddha nature and might someday accept the sūtra.”

This Universe is One Great Being

When we thoroughly consider about Ichinen Sanzen of Ri deeply, we come to understand that everything in the Universe depends on each other, relates with each other, and does not exist independently. Everything exists as one. In the cycle of nature, everything in the Universe has its own role by making others active with each other and supporting each other. In other words, this Universe is one great being. Nothing has an independent existence. We human beings also have our own role as a part of the great life of the Universe.

Buddha Seed: Understanding the Odaimoku